| America's Home for Racing | |

|---|---|

| |

Quad-oval (1960–present) | |

| Location | 5555 Concord Parkway South, Concord, North Carolina, 28027 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (UTC−4 DST) |

| Coordinates | 35°21′09″N 80°40′57″W / 35.35250°N 80.68250°W |

| Owner | Speedway Motorsports & the Smith family (1974, 1976–present) Richard Howard (April 1964–1974, 1975–1976) A. C. Goines (April 1963–April 1964) United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina (November 1961–April 1963) Duke Ellington (June–November 1961) Bruton Smith and Curtis Turner (1959–1961) |

| Broke ground | 28 July 1959 |

| Opened | 15 June 1960 |

| Construction cost | $2 million USD |

| Former names | Lowe's Motor Speedway (1999–2009) |

| Major events | Current: NASCAR Cup Series Coca-Cola 600 (1960–present) Bank of America Roval 400 (1960–present) NASCAR All-Star Race (1985, 1987–2019) Former: IMSA SportsCar Championship Grand Prix of Charlotte (1971, 1974, 1982–1986, 2000, 2020) Pirelli World Challenge (2000, 2007) Indy Racing League VisionAire 500K (1997–1999) Can-Am (1978–1979) |

| Website | charlottemotorspeedway |

| Quad Oval (1960–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 1.500 miles (2.414 km) |

| Turns | 4 |

| Banking | Turns: 24° Straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 0:24.735 ( |

| NASCAR Road Course "Roval" (2019–present)[a] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.280 miles (3.669 km) |

| Turns | 17 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:18.188 ( |

| NASCAR Road Course "Roval" (2018)[a] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.280 miles (3.669 km) |

| Turns | 17 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:18.078 ( |

| Roval (1971–2014) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.250 miles (3.621 km) |

| Turns | 18 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:05.524 ( |

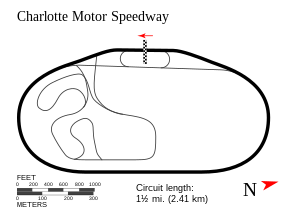

Charlotte Motor Speedway (formerly known as Lowe's Motor Speedway from 1999 to 2009 due to sponsorship reasons) is a 1.500-mile (2.414 km) quad-oval intermediate speedway in Concord, North Carolina. It has hosted various major races since its inaugural season of racing in 1960, including NASCAR, IndyCar, and IMSA SportsCar Championship races. The track is currently owned by Speedway Motorsports, LLC (SMI), with Greg Walter serving as the track's general manager. Charlotte Motor Speedway is served by U.S. Route 29.

The speedway has a capacity of 95,000 as of 2021, down from its peak of over 170,000 in the 1990s and 2000s. The track features numerous amenities, including a Speedway Club, condos, and a seven-story tower located on the complex for office space and souvenirs. In addition, the Charlotte Motor Speedway complex features numerous adjacent tracks, including a 1⁄5 mile (0.32 km) clay short track, a 2⁄5 mile (0.64 km) dirt track, and a 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) long drag strip. The main track also features an infield road course that is used with the oval to make a "roval".

With the rise of popularity in stock car racing in the American Southeast that began in the late 1940s and stretched into the 1950s, racing promoter Bruton Smith sought to build a state-of-the-art facility. At the same time, driver and businessman Curtis Turner sought to do the same. After initially refusing, Turner eventually partnered with Smith after Smith agreed to sell shares needed for the track's construction. Construction of the track was completed in less than 11 months. The track immediately faced a litany of issues, particularly financial woes. Within the track's first decade of existence, ownership changed hands numerous times, with Smith and Turner both leaving. After a period of stability under the ownership of Richard Howard from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Smith and his new partner, racing promoter and eventual longtime track general manager Humpy Wheeler, completed a takeover of the track in 1976. Since then, the Smith family and their company, SMI, have directed the track's expansion and growth into becoming one of the largest sports facilities in the United States.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:54 881101 07352 82023 721208 724

-

World of Outlaws CASE Late Models | The Dirt Track at Charlotte | Nov. 4, 2023 | HIGHLIGHTS

-

World of Outlaws NOS Energy Drink Sprint Cars. World Finals Charlotte November 5, 2022 | HIGHLIGHTS

-

World of Outlaws CASE Late Models World Finals. Charlotte, November 5, 2022 | HIGHLIGHTS

-

YOU MAKE THE CALL: John Sossoman vs. Robby Faggart - June 19, 2018 - Charlotte Motor Speedway

-

Coca-Cola 600 from Charlotte Motor Speedway | NASCAR Cup Series Full Race Replay

Transcription

Description

Configurations

The speedway in its current form is measured at 1.5 miles (2.4 km), with 24 degrees of banking in the turns and five degrees of banking on the track's frontstretch and backstretch.[1] Within the main track's frontstretch, there is a 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) oval that was built in 1991 that is primarily used for legends car racing.[2]

Numerous tracks exist in the track's infield. In 1970, the track announced plans for an infield road course that was connected to the speedway's backstretch. According to then-general manager Richard Howard, original plans for the speedway included a road course, but was cut due to budget issues.[3] The original road course's length has varied in reports; the track has been reported to be as short as 1.75 miles (2.82 km) according to the Salisbury Post,[4] and as long 1.9 miles (3.1 km) long according to The Charlotte Observer. The road course held its first races on May 22, 1971 as part of the 1971 World 600 race weekend.[5] By August 1974, the track was reconfigured to become 2.25 miles (3.62 km).[6] In 2018, the road course was modified to suit NASCAR racing, adding a backstretch chicane.[7] In 2019, the speedway's chicane was modified.[8] In 2020, the track constructed a purpose-built go-kart track in the track's infield.[9]

Amenities

The track is located directly next to U.S. Route 29.[10][11] At the time of the track's initial construction, the complex covered 551 acres and had a capacity of around 30,000.[12] Over the span of several decades, the track and its complex has expanded and been improved numerous times. Throughout the ownership of Bruton Smith, the track saw capacity grow, seeing a peak of over 170,000 by the end of the 1980s.[13] However, since the 2000s, capacity has seen a decrease, with multiple grandstands being demolished in the 2010s.[14][15] As of 2021, the track is reported to have a capacity of 95,000.[16] The complex has also expanded to around 2,000 acres as of 2020.[17]

Numerous buildings are located on the complex for various uses. In 1983, to celebrate the track's 25th anniversary, the track announced the construction of 36 condominiums that were built to overlook the track's first turn.[18] By the time the project was completed in mid-1984, the amount of condos increased to 40, and all were sold out by the end of 1983.[19][20] At the end of 1984, the track announced the construction of a mall underneath the condos.[21] In 1987, the track announced the construction of a members-only private club and restaurant named The Speedway Club, with annual membership starting at $6,500 (adjusted for inflation, $17,432).[22]

Adjacent tracks

The Charlotte Motor Speedway complex has two adjacent tracks and a dragstrip near the main speedway. By 1993, the track built a 1⁄5 mile (0.32 km) clay short track that was made to conduct dirt legends car races.[23] On August 10, 1999, then-general manager Humpy Wheeler announced the construction of a new 3⁄8 mile (0.60 km) dirt track that was to be constructed across the main speedway.[24] By January 2000, however, the track length changed to become a 2⁄5 mile (0.64 km) track.[25] The track held its first races on May 28, 2000, with the track featuring a lighting system and a capacity of 15,000.[26][25]

In August 2007, owner of Speedway Motorsports, Bruton Smith, announced plans to build a drag strip on the complex.[27] Although the plan faced heavy opposition initially from local politicians,[28] the drag strip was eventually built after Smith threatened to close down the speedway due to opposition,[29] coercing the city to give him an incentive package of approximately $80 million using fears that shutting down the speedway would cripple the Concord economy.[30][31] The drag strip, which cost $60 million to build,[32] held its first races in September 2008.[33]

History

Planning and construction

Stock car racing, with its origins tracing back to moonshiners during the Prohibition era, oversaw a rise of popularity within the American Southeast throughout the 1940s and 1950s. With this rise, new modern tracks, such as Darlington Raceway, were built across the Southeast.[34] In the late 1950s, Bruton Smith, a promoter who had found major success promoting races across the Carolinas, sought to build his own racetrack. In 1956, he partnered with businessman John William Propst Jr. to build a racetrack. At the same time, driver and successful timber businessman, Curtis Turner, sought to do the same, collaborating with local track officials.[34][35] In 1958, Propst suffered a heart attack, backing out of the partnership due to health issues. Due to this, Smith sought to partner with Turner. After a few weeks of initial success, in a meeting at the Barringer Hotel, Turner declined to partner with Smith. For numerous reasons, including the feeling of betrayal, the fact that Turner did not have enough funds to start his own track, and knowing that the city of Charlotte could only support one track, Smith announced his intentions of building his own speedway to rival Turner's on April 22, 1959, the same day Turner announced his track.[34][35] On May 8, Turner announced the track would be built bordering U.S. Route 29, inside of Cabarrus County, North Carolina, with a capacity of 30,000.[12] However, Turner struggled to sell the 300,000 shares needed. Turner eventually agreed to partner with Smith, with Smith becoming the vice president of the track and selling 100,000 shares.[36][35] Additional stocks to be sold were added in December 1959[37] and April 1960.[38]

Groundbreaking on the track commenced on July 28, 1959. It was meant to start two months earlier, but was delayed due to legal issues.[39] The track was immediately plagued with numerous construction issues. The construction crew who worked on the track discovered large veins of granite underneath the track's soil shortly after groundbreaking. To get rid of it, grading contractor W. Owen Flowe decided to blast it with dynamite, causing delays.[34] Reports of feral hornets were also made, leading to multiple workers quitting.[40] In March 1960, three snowstorms delayed construction even further;[34] although, the track's publicity director insisted that the track's construction was "still ahead of schedule".[41] By the end of March, developers considered scrapping plans for grandstands to save time.[42] The issues caused the track's first major race, the NASCAR-sanctioned 1960 World 600, to be delayed from its original date on May 29 to June 19.[43] Longtime NASCAR mechanic Smokey Yunick called the construction location "a giant mistake. If they'd have searched North Carolina for the worst possible place to build a racetrack, that's where they built it."[34] Smith blames Turner for the delays; according to Smith, Turner would commonly hire people irrationally while under the influence of alcohol, with Smith having to turn them away.[34] Despite these issues, the project saw additional funding and a $300,000 loan from Washington D.C. businessman James L. McIlvaine, who was so confident that the project would succeed that he stated in The Charlotte Observer, "This is going to be one of the best investments I've ever made, and I've made some good ones."[44]

Nearing the end of the track's construction, a mutiny formed between Flowe and his workers, citing unpaid fees and bounced checks. On June 9, days before the World 600, Flowe parked several earthmovers on the track and stopped construction, with Flowe threatening to sue.[45] Disputing accounts exist of what happened to suppress it; according to Flowe, he and his workers were threatened with a gun by numerous people, including Smith and Turner, threatening to shoot them if they did not continue working.[46] According to Smith, only Turner showed up with a shotgun and proceeded to "[act] like he was somebody" before a guard took away his gun.[34] Eventually, construction resumed, and construction was barely completed by the time the first days of activities occurred for the 1960 World 600.[34][47][48] In later interviews, Smith called it a "miracle" the track was built, having admitted to losing $150,000 building it.[35][49] The track cost around two million dollars according to McIlvaine,[50] with $74,000 in debts owed to Flowe by the end of its initial construction.[51]

Early extreme track and financial troubles

The track officially opened to cars for a practice session on June 15, 1960. Immediately, the track saw issues. During the track's first day, incomplete facilities were reported by The State.[52] To further compound problems, the asphalt of the track had several holes due to speeds of approximately 130 miles per hour (210 km/h) of the track. The issue had gotten so prevalent that Charlotte Observer writer George Cunningham reported that "four gravel-deep fox holes grew... out of the second turn. And practically the entire surface on the third and fourth turns resembled an old lady's wrinkled face".[53] However, some hope remained that the track would cure at faster speeds, including driver Fireball Roberts.[54] Track leaders ordered a hasty repave of the track, and by the next day, most of the track's surface held up.[55] By June 18, more financial problems ensued; the track was sued by Roy E. Thomas, a souvenir program advertising seller, for $10,000 (adjusted for inflation, $102,992) for breach of contract because he was let go of his job.[56] By race day, Smith began to pray that the race would go over halfway so he would not have to give out refunds.[34] During the race itself, track surface issues resurfaced; numerous mechanical problems, including blown tires, broken axles, suspensions giving out, and other problems were reported by drivers such as Tom Pistone, Doug Yates, and Ned Jarrett due to the track's rough surface. Another driver, Emanuel Zervakis, stated, "It's rough as hell! All the cars will have to be rebuilt... there's no doubt about it".[57] In addition, the track was reported to have come apart in numerous areas, with drivers having to avoid flying pieces of asphalt during the race.[34] Max Muhlehurn, writer for The Charlotte News, stated that "The 600 will go down in history as the only race ever run in which drivers were forced to dodge track blemishes more often than other cars".[58]

By July 17, McIlvaine spread rumors that the track would appoint new management, under either NASCAR president Bill France Sr. or Darlington Raceway president Bob Colvin.[50] The rumor was repelled by both Smith and Turner, with Turner threatening legal action.[59] Within the next couple months, numerous claims of Smith and Turner owing money to various groups and companies were made, including owing $90,000 to the Connecticut General Life Insurance Co.,[60] $40,200 to the Internal Revenue Service,[61] $65,000 to Propst and his construction company, and $204,000 to McDevitt Street and Co. The track also was found to have defaulted on their initial mortgage.[62] By August, only Propst had been paid off, with further repaves scheduled to fix track surface issues.[63] In November 22, the track was reported to have amassed around $1 million in debts.[64] Two more lawsuits were filed in January 1961 by excavating companies.[65] In February, the track wished to host a National Football League (NFL) exhibition game between the Washington Redskins and the Philadelphia Eagles;[66] however, the deal fell through when Smith found terms from Redskins owner George Preston Marshall to be unreasonable.[67]

On March 1, 1961, Flowe filed a civil action lawsuit against the track, seeking to recover $138,155.28 in reparations for construction costs, claiming breach of contract.[68] Three months later, as of result of McIlvaine threatening the foreclosure and subsequent auction of the track, Turner and Smith resigned from the board of directors, with Smith staying as a promotional director.[69] Board of directors member Duke Ellington replaced Turner as the track's general manager. Turner later accused Smith and Ellington on conspiring to oust him, along with stating inflated profits.[70] In July, Turner and his investor group announced plans to regain control of the track by either buying the track in a public sale or accumulating enough stock.[71] By August, even though the track experienced an "unusually successful" 1961 World 600, they warned stockholders that the track was in "serious trouble and can only gain financial stability through the arrangement of long-term financing immediately".[72] By the beginning of October, with the track still having $500,000 in debt, foreclosure proceedings began, with the track being planned to be sold at auction on October 30.[73] In attempts to stop it, numerous solutions were brought up, including seeking to take out a "miracle" loan[74] and Smith partnering to raise $600,000 with investors to save the track.[75] After the auction was delayed,[76] on November 3, James Braxton Craven Jr., a judge for the United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina, ruled to let the district court take over and manage the track, with the track entering Chapter 10 bankruptcy, ceasing all officers' and directors' positions. The track was also protected from creditors by the count, essentially becoming a ward.[77][78]

Bankruptcy under federal court control

In the aftermath of Craven's ruling, Robert Nelson Robinson, a local Charlotte lawyer, was appointed to run the track by Craven.[79] Numerous loan offers to pull the track out of its financial woes, including separate offers from businessmen Roger D. Edwards[80] and Dwight Cross were made.[81] On December 9, Craven ruled to let the track's management find loans and funds to creditors who were seeking money, with Robinson being ordered to come up with a plan to ensure the $900,000 payment to various creditors, essentially saving the track.[82] By the beginning of January 1962, however, no progress was made, leading to threats from Craven to liquidate the track by March if no plan was made.[83] By the end of the month, a stockholders committee, headed by A. C. Goines, planned to ask the nearly 2,300 shareholders of the track to buy trustee certificates ranging from $100-1,000, with a plan to raise $300,000; half of the $600,000 needed to start reorganization.[84] After a "wonderful" initial stockholder meeting on February 18,[85] a last-ditch effort was scheduled to raise $50,000 six days later.[86] On the day of the meeting, the committee was successful in raising the $300,000 needed.[87] However, Cross, who was planning to loan the rest of the funds needed, was rejected.[88] By May, Craven ordered a investigation on the track to find out instances of mismanagement.[89] By July, although Craven was convinced the track could be saved,[90] the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was asked to assist with the investigation due to preliminary findings of mismanagement and potential fraud.[91][92] Eventually, a reorganization plan hearing was set for November 5.[93]

In October, a new $345,000 loan from McIlvaine was guaranteed despite the track owing McIlvaine over $300,000, taking more financial pressure off the track.[94] The next month, Craven approved a plan made by Robinson that would let stockholders and creditors vote on a reorganization plan from December to January 3, 1963.[95][96] Although the plan initially did not receive enough support from creditors,[97] the plan was eventually approved,[98] with Craven giving final approval for a stock sale in February.[99] By April, the plan saw major success, with the track paying over $740,000 of its debt.[100] In mid-April, Craven let the track back into private owners' hands, headed by an 11-person board of directors led by A. C. Goines that was to last for at least one year, completing the reorganization process.[101] In that same year, Bruton Smith left his job as a result of him being found guilty of failing to properly file tax returns in 1955 and 1956.[102][103]

Richard Howard era, stabilization

By December 1963, Goines declared while announcing a 10% stock dividend, "We've taken some bitter medicine, but the patient has been saved".[104] By February 1964, the track saw a profit for the first time.[105] Goines resigned after the mandatory one-year period, with his position being filled by leading stockholder Richard Howard, a furniture store owner.[106] The track later oversaw numerous driver fatalities in the mid-1960s; longtime driver Glenn "Fireball" Roberts died on July 2, 1964 due to complications from a fiery crash at the 1964 World 600,[107] and Harold Kite, a World War II veteran, died on October 17, 1965, during the 1965 National 400 in a crash on the race's first lap.[108]

Under the leadership of Howard, the track was able to pay off its mortgage three years early, finally ending the last of the track's financial woes.[109] Throughout Howard's tenure, he was seen as a "good ol' country boy" who spent conservatively on the track; however, he was willing to renovate parts of the track and add capacity.[110] In 1965, the track opted to diversify their holdings, buying out the Rightway Investment Corporation, an insurance finance company.[111] By 1970, the track announced constructions of a new road course,[3] along with new grandstands according to tax records.[112] By the early 1970s, the track was increasing their profits year-by-year.[113]

Bruton Smith and Humpy Wheeler's takeover

In the mid-1970s, after a successful stint in the car dealership business, Smith, keeping his true thoughts away from the public at the time, thought that owning the track during this time would be an highly profitable venture, with the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and its subsidiary Winston introducing their sponsorship of the NASCAR Cup Series in 1970.[114] By 1973, Smith bought almost 500,000 shares from his initial amount of 40,000 when he resigned, with Smith stating that he did not know why he bought as many as he did.[115] By early 1974, despite an attempt to stop elections for the track's board of directors,[116] Smith was elected as the track's chairman, effectively placing him back in charge. Howard was elected as the track's president.[117][103] Later that year, Howard announced a $2.5 million renovation of the track, aimed at improving the physical appearance of the track and adding seating.[118]

Throughout 1975, Howard and Smith spat on each other in the media, entering a fierce battle for control. In January, Howard regained control of the board of directors despite threatening to resign.[119] By early February, Howard stated that that he was tired of the track being run from Illinois, where Smith lived. In response, Smith accused him of consolidating too much power along with financial irregularities.[120] In July, Smith bought around 80,000 shares from Howard's relatives, which was considered a major turning point in the battle for control.[121] On August 29, H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler, a former public relations representative for various companies, was hired as the track's development director.[122] With the hire, Howard felt his position was threatened, with local media predicting that Wheeler's hiring was the final piece for a total takeover by Smith.[123][110] By October 5, The Atlanta Constitution reported that the 1975 National 500 was to be Howard's final race with the track, with a final decision to come on January 30, 1976, the day of the annual stockholders' meeting.[124] Although Howard initially denied these claims[125] and later stated interest of taking a consultant job with Smith, Howard stated he was "99% certain" of leaving by October 23.[126] On the day of the meeting, a tearful Howard officially announced his resignation from his position, essentially giving Smith full control over the track, with Wheeler filling in as president.[127]

Humpy Wheeler era, promotions, failed NFL proposal

Under the track leadership of Wheeler and Smith, the track became known for its promotions and rapid expansion to modernize and promote the facility. In Wheeler's first year as president, he announced a $3–5 million renovation that was to be completed in 1981.[128] Wheeler became known in the following years for pulling off elaborate and unique promotions. In 1976, he convinced Janet Guthrie to enter the 1976 World 600 to attract female spectators.[129][130] In 1977, to promote a rivalry between longtime driver Cale Yarborough and newcomer Darrell Waltrip, he paraded around a contraption that poked fun at Waltrip's nickname, "Jaws", and Yarborough's sponsor, Holly Farms Poultry. Wheeler placed a dead chicken inside a dead shark's mouth, placed it on a pickup truck's sling, and paraded it before first round qualifying of the 1977 NAPA National 500.[131] In 1980, the track announced further renovations worth $16 million, with a stated goal of bringing capacity to 150,000.[132] In 1983, the track announced the construction of 36 condominiums;[18] the number later increased for 40, and all sold out by its completion by 1984 despite initial mockery.[19][20]

In 1985, the city of Charlotte sought to attract a professional football team. In March, Smith announced plans to build a football stadium on the track's frontstretch,[133] with a capacity of 76,000, temporary endzone grandstands, and retractable grandstand seating behind the track's pit road.[134] Original plans for the track had included a football stadium, but was scrapped due to numerous factors in construction.[135][136] During the official announcement on March 13, Smith stated that he would build it if either the local government or investors gave him $10 million.[134] He oversaw competition from fellow Charlotte businessman George Shinn, who wanted either a National Football League (NFL) or a team in the fledgling United States Football League (USFL). However, Smith only wanted an NFL team.[137] The city refused to assist with construction costs, and all plans died within the year;[136] however, Smith did state renewed interest of hosting an NFL team at the track two years later.[138]

Mass expansion and improvement, injury-riddled period

In 1987, the track built a membership-exclusive club and restaurant named The Speedway Club.[22] By the end of the 1980s, the track had a maximum capacity of 170,922.[13] In 1991, Smith directed the installation of lights at the track with the help of Iowa-based Musco Lighting. At the time, it was viewed as a major feat as no oval track as big as the Charlotte Motor Speedway had ever implemented such a system.[139] The lights were installed by April 1992.[140] In 1994, the track renovated its garage area at a cost of around $1 million, drawing praise from driver Dale Jarrett.[141] In 1999, the track partnered with hardware retail chain Lowe's to buy out naming rights to the track, the first time a corporate sponsor ever had naming rights to a track.[142]

Throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s, the track oversaw numerous injuries and fatalities from both drivers and spectators. In 1989, Wheeler created the NASCAR Sportsman Division, a series that had the intended goal of giving short track drivers experience on longer tracks. The track played host to numerous races.[143] The series immediately gained a reputation for being a dangerous division due to a series of crashes within the span of six years at the track. A series of three fatal crashes occurred; David Gaines in 1990,[144] Gary Batson in 1992,[145] and Russell Phillips in 1995, with the third being decapitated when his head hit a caution light.[146][147] By the end of 1995, Wheeler gave control of the series to NASCAR, who ended it quickly afterward in 1996.[148][147] In 1999, during a Indy Racing League race, the 1999 VisionAire 500K, an early accident involving Stan Wattles and John Paul Jr. occurred on the speedway's front stretch, resulting in heavy debris. Wattles' right rear wheel and tire assembly flew into the grandstands at high speeds, killing three people and injuring eight more, cancelling the race.[149] In 2000, after the 2000 The Winston, a pedestrian bridge collapsed, injuring 107 people,[150] which was later blamed on the manufacturer of the bridge for using an improper additive.[151][152] In the next two years, two ARCA drivers died in accidents; Blaise Alexander in 2001,[153] and Eric Martin in 2002.[154]

In 2005, the track announced a repave, with the track using a process called levigation to smooth out bumps on the track's surface.[155] The repave led to numerous problems for both of the track's NASCAR race weekends in 2005, leading to another repave in 2006.[156][157] In 2007, Smith announced plans to construct a drag strip.[27] The plan was met with heavy criticism from the Concord City Council, making a special legislative session to decide whether to block plans for it.[28] Smith vehemently opposed it, deciding to start preliminary grading on it regardless.[158] On October 2, the council voted unanimously to block Smith's plans.[159] In response, Smith threatened to shut down the track or to relegate it to a testing facility unless the decision was reversed, which would lead to a massive financial blow in the Concord economy.[29] The council quickly backtracked, and tried to convince Smith to stay by offering Smith a lofty incentive package of $80 million, a street named in his honor, and a tax break along with letting him build the drag strip.[30] On November 26, Smith stated his final decision in letting the track continue as is, stating, "We're here forever".[31]

Turbulent retirement of Wheeler

Tensions between Smith and Wheeler had been documented since 1991, with the two being in "constant disagreement" over topics.[160] By 2008, Wheeler grew angry at several new developments Smith directed, including the controversial drag strip.[161] On May 21, 2008, Wheeler announced his abrupt retirement from his position at the track that was effective after the 2008 Coca-Cola 600, ending a reign since 1975.[162] Although Smith claimed that he offered Wheeler a consulting job and that Wheeler himself hoped for a part-time position,[163][164] he would leave all track duties related to the track.[162] Wheeler was replaced by Marcus Smith, one of Smith's sons.[165] In 2009, corporate sponsor Lowe's ended its partnership with the track, ending an 11-year partnership, with the track reverting back to the "Charlotte Motor Speedway" name.[166]

Steady attendance declines, renovations

Throughout the 2010s, the track oversaw steady attendance declines that correlated with an overall attendance decline within NASCAR. As a result, the track tore down 41,000 seats in 2014,[14] and an unspecified amount of seats in 2017.[15] In 2017, the track was used for filming of the movie Logan Lucky, a fictional movie about a heist that involved a group of people stealing $14 million from the track.[167] In 2018, Marcus stepped down from general manager responsibilities to focus on running SMI as its CEO, handing the position over to the speedway's executive vice president at the time, Greg Walter. In interviews, Walter expressed a desire for expanding the track's uses for endeavors other than racing, along with further renovations.[168] In 2021, the NASCAR All-Star Race, which had been held at the track annually with two exceptions in 1986 and 2020, was moved to the Texas Motor Speedway to try and reverse sagging attendance at Texas.[169]

The track has seen numerous renovations and additions since the 2010s. In 2011, Marcus directed the construction of a 200 foot by 80 foot television screen on the track's backstretch, demolishing old backstretch seats in the process.[170] In 2015, the track renovated its barriers in response to Kyle Busch's injury at the Daytona International Speedway in February.[171] In 2023, the track announced plans to build a dedicated road course.[172]

Events

Racing events

NASCAR

Since 1960, the track has held two annual NASCAR Cup Series races per year: the World 600 (known as the Coca-Cola 600 for sponsorship reasons) and the Bank of America Roval 400. The World 600 was originally planned to be run on American Independence Day weekend;[173] however, after the success of the inaugural Firecracker 400 at Daytona International Speedway which was held on July 4, this was put under doubt.[174] On September 23, 1959, a race date was set for Memorial Day weekend.[175] Upon the race's inaugural iteration, the race became one of the longest, largest, and highest-paying motor races in the world.[176][177] Since its inaugural race, the race has become a staple on the NASCAR schedule, becoming a "crown jewel" event for being the longest race on the NASCAR Cup Series schedule annually.[178][179]

The latter was formerly a 500-mile race that was commonly known as the National 500, which was run in October. Initially a 400-mile race, the inaugural race was officially announced on June 29, 1960, two weeks after the inaugural World 600.[180] In 1966, the race distance increased to 501 miles, which remained until 2018.[181] In 2018, in attempts to reverse declining attendance for the race, the race both decreased to 400 kilometers and was run on a specialized "roval" course.[182][183]

In 1985, Wheeler and the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company directed the creation of The Winston (now called the NASCAR All-Star Race), a race that featured race winners of the previous season.[184] Since 1987, the track ran the event annually, with various changes to its format and eligibility rules throughout its time.[185] However, in 2020, the race was moved to the Bristol Motor Speedway due to COVID-19 restrictions.[186] In 2021, the race officially moved to the Texas Motor Speedway to reverse declining attendance at Texas.[169]

Open wheel racing

In late 1979, the United States Auto Club (USAC) announced plans to run a 500 kilometres (310 mi) race in October 1980.[187] However, the race was cancelled in April due to an agreement with USAC and Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART).[188] In December 1996, IndyCar announced plans for an IndyCar race to be held in July 1997.[189] The race ran for three years; the last race was cancelled after an accident caused flying debris that killed three spectators.[149]

Other racing series

Numerous runnings of the Grand Prix of Charlotte, a sports car event, have been run by various organizations. In 2000, the track held a one-off Grand Prix of Charlotte that was sanctioned American Le Mans Series.[190] The race was last run in 2020 by the IMSA SportsCar Championship.[191]

Festivals

On August 10, 1974, the track hosted the August Jam. Regarded as "Carolina's Woodstock", the festival drew over 200,000 people, more than double than what was expected due to a security breach. The festival unintentionally became the largest music festival in North Carolina history.[192][193] The concert soon gained a violent reputation; Richard Howard, president of the track, compared the actions of spectators to Japanese Army suicide attacks at the Battle of Okinawa, with damages totaling $50,000.[194]

From 2013 to 2018, the track held the Carolina Rebellion festival.[195][196] Since 2021, the track has hosted a branch of the touring Breakaway Festival.[197] In 2024, in addition to the Breakaway Festival, its organizers also plan to a second show at the track for 2024 tailored for EDM that is managed by the Breakaway Festival.[198] That same year, the track also announced it would host the inaugural edition of the Lovin’ Life Music Fest.[199]

Other events

The speedway hosts an annual Christmas-themed drive-thru lights show, a tradition that started in 2010.[200] In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the track hosted high school graduations for 10 high schools within the Cabarrus County area.[201]

Lap records

As of May 2023, the fastest official race lap records at the Charlotte Motor Speedway are listed as:

Notes

References

- ^ "Charlotte Motor Speedway". ESPN. December 13, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (March 17, 1991). "Legends race set for Charlotte". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 11B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "CMS Officials Plan Road Course In Near Future". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. May 15, 1970. pp. 17D. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Two Road Races Open '600' Slate". Salisbury Post. May 16, 1971. pp. 5D. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Road Course Opening At CMS". The Charlotte Observer. May 21, 1971. pp. 4E. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (August 17, 1974). "Stockers Battle Sports Car Set At The Speedway". The Charlotte News. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kiser, Jesse (February 8, 2018). "Road Course+Speedway Oval=Roval: NASCAR's New Late-Season Road Course". The Drive. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Crandall, Kelly (June 23, 2019). "Charlotte announces 'Roval' changes". Racer. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Andrejev, Alex (January 28, 2020). "Track plans changes for 2020 season". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whisenant, David (May 19, 2017). "Traffic to be heavy around Charlotte Motor Speedway for next ten days". WBTV. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Hagwood, Kayland (July 26, 2023). "'It could've been me' | Charlotteans express concern about speeding drivers after deadly crash near Charlotte Motor Speedway". WCNC-TV. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Muhleman, Max (May 8, 1959). "Million-Dollar Race Track To Be Built North Of City". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 2A. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b McKee, Sandra (July 7, 1989). "Charlotte sets standard for motor speedways". Press Enterprise. The Washington Post. p. 23. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Whisenant, David (December 12, 2015). "Charlotte Motor Speedway pulling out 41,000 seats, eliminating Diamond Tower Terrace". WBTV. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Peralta, Katherine (March 20, 2017). "NASCAR fans may notice some changes soon at Charlotte Motor Speedway". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Hauser, Jeff (May 14, 2021). "Charlotte Motor Speedway to reopen at full capacity for Coca-Cola 600". WBT. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Andrejev, Alex (June 5, 2020). "All-Star race at Charlotte is in July on updated schedule". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Fletman, Abbe (June 24, 1983). "Speedway To Go Condo". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 5C. Retrieved August 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Fletman, Abbe (October 9, 1983). "Living Room, Bedrooms... And A View Of The Race". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 13B. Retrieved August 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Heffner, Earl (May 25, 1984). "'Speedways' In Ancient Rome". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 18A. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charlotte Motor Speedway adding stores under condos". The Charlotte News. November 26, 1984. pp. 9A. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Powell, Lew (August 25, 1987). "Puttin' On The RITZ High Above The PITS". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A, 11A. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cain, Woody (July 25, 1993). "Legends racing: Same skills, cheaper thrills". The Charlotte Observer. p. 18. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David (August 11, 1999). "Wheeler kicks up dirt again". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 5B. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Poole, David; Utter, Jim (January 13, 2000). "Earnhardt not quite ready to put repaired back to test". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 3C. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Scott, David (May 29, 2000). "Lighting innovators shine at speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 7D. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Bell, Adam; Poole, David (August 31, 2007). "LMS considering adding drag strip". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10C. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Durhams, Sharif (September 27, 2007). "Concord hitting brakes on drag strip plan?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Durhams, Sharif; Poole, David (October 3, 2007). "Smith: My way or no speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 16A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Durhams, Sharif (October 25, 2007). "Where the street has his name?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 14A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b George, Jefferson; Bell, Adam (November 27, 2007). "'We're here forever.'". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 9A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David (January 25, 2008). "New drag strip to provide region vroom to grow". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 8C. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ George, Jefferson (September 11, 2008). "Revving economic engine". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 2D. Retrieved January 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Poole, David; St. Onge, Peter (May 24, 2009). "A wild ride for everybody". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 13C, 14C, 15C. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Mildenburg, David (October 1, 1995). "Risk At Every Turn". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 14A, 15A. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harding, Larry (June 5, 1959). "Speedway Elects Bruton Smith VP". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 11B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charlotte Speedway To Issue More Stock". The Charlotte News. December 1, 1959. pp. 5A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (April 14, 1960). "The 600 Sandwich". The Charlotte News. pp. 14A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (July 28, 1959). "Turner's Track In Gear Now With Ground-Breaking". The Charlotte News. pp. 2B. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Crissman, Bob (January 24, 1960). "Track An Earth-Moving Project". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 3D. Retrieved February 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Crissman, Bob (March 18, 1960). "Driving Flocks Plan 25,000 Mile Marathon". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 12B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (March 26, 1960). "Battle Of The Bog". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 3A. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (May 19, 1960). "Weather Blamed For Delay Of 'World 600' To June 19". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Neill, Rolfe (June 12, 1960). "Sugar Daddy". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 2D. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (June 10, 1960). "Speedway Checks Bad, Angry Contractor Says". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 5B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (June 10, 1960). "Speedway, Contractor Fuss". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (June 15, 1960). "Are Stock Drivers Honest?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8C. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (June 20, 1960). "The Show Won't Be Forgotten". The Charlotte News. pp. 2B. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kennedy, John W. (October 7, 1979). "Concord's Smith Helped Build Charlotte Speedway". Rocky Mount Telegram. p. 39. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Cunningham, George (July 17, 1960). "Speedway's Management To Change". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Neill, Rolfe (June 11, 1960). "Speedway Spokesman Says Current Debts Will Be Paid". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Talbert, Bob (June 15, 1960). "'600' Officials Take Issue". The State. pp. 4B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (June 16, 1960). "130-Plus Speeds Rip Holes In '600' Track". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 7C. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (June 16, 1960). "Speedway – Big Test, Big Problem". The Charlotte News. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (June 17, 1960). "Roberts (Who Else?) Wins Pole Position". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 5D. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Clark, Ken (June 18, 1960). "Speedway Sued; Race Still On". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Helms, Herman (June 20, 1960). "'Demolition Derby' Takes Heavy Toll On Big Field". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (July 19, 1960). "Repair Job Begins". The Charlotte News. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (July 18, 1960). "Turner, Smith Call Rumor 'Wishful Thinking'". The Charlotte News. pp. 3B. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (July 1, 1960). "Turner, Others Are Facing Claim". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Claiborne, Jack (August 19, 1960). "Speedway President Disputes Tax Claim". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 13A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Neill, Rolfe (September 8, 1960). "Speedway Fee Disputed By Turner, Smith". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 4A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway, Contractor Now Settled; Repaving Begins". The Charlotte News. August 5, 1960. pp. 9A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Neill, Rolfe (November 22, 1960). "Speedway Planning New Issue". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 17A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "2 Suits Filed Against Motor Speedway Here". The Charlotte Observer. January 22, 1961. pp. 16A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (February 2, 1961). "'Skins Want 'Money' Friday". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelley, Whitey (February 12, 1961). "Marshall Must Give A Little". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5D. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "$138,155 Suit Filed In Cabarrus Court Against Speedway". The Charlotte Observer. March 1, 1961. pp. 7B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Murleman, Max (June 9, 1961). "Foreclosure Threat Led To Quittings". The Charlotte News. pp. 2B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (June 15, 1961). "Ellington: 'This Is No Time To Comment'". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 4B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (July 13, 1961). "CMS, Betting At Races Sought By Turner?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8B, 9B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (August 31, 1961). "CMS Life Hinges On '400'; World 600 Grossed $398,042". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (October 2, 1961). "Creditors Crack Down On Track". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shinn, Jerry (October 28, 1961). "No 'Miracle' Yet For Speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 4B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (October 4, 1961). "Bruton Smith Offers Proposal To Save Track". The Charlotte News. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McElheny, Victor K. (October 29, 1961). "Raceway Auction Delayed". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (November 3, 1961). "Judge Puts Off Speedway Sale". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A, 6A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Martin, Gerald (February 2, 1976). "Track's New Owner Has Costly Dream". The News & Observer. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (November 4, 1961). "Speedway Trustee Is Named". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 12B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (November 15, 1961). "NC Financier Offers To Save Speedway". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (December 8, 1961). "$650,000 Offered To Ailing Raceway". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A, 5A. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (December 9, 1961). "Speedway Gets Stay, Race Okay". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A, 6A. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (January 4, 1962). "U.S. Judge Tells Speedway To Act Or Quit Business". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (January 24, 1962). "Race Track Stockholders Asked For 'Faith' Money". The Charlotte News. pp. 8A. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "Track Needs $50,000 More". The Charlotte News. February 19, 1962. pp. 6A. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (February 23, 1962). "Track Sets Do-Or-Die Stockholders' Meeting". The Charlotte News. pp. 8B.

- ^ Munn, Porter (February 25, 1962). "Speedway Goal Of $300,000 Is Met In Time". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (March 21, 1962). "Cross' Loan Not Acceptable". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (May 19, 1962). "Judge Orders 111 Questioned On Speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (July 6, 1962). "Judge: Track Can Be Saved". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 4A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (July 6, 1962). "Track Wrongs Hinted". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (July 7, 1962). "Judge: Probe Speedway, If..." The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Murphy, Harry (July 18, 1962). "Speedway Hearing Scheduled Nov. 5". The Charlotte News. pp. 7B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (October 20, 1962). "'No-Strings' Loan To Let Speedway Pay Off Debts". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 12B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway Plan Ballots Will Be Sent". The Charlotte Observer. November 29, 1962. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway Granted More Voting Time". The Charlotte News. December 21, 1962. pp. 4A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (January 4, 1963). "Speedway In Trouble Again; Creditors Foil Reorganization". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Munn, Porter (January 5, 1963). "Creditors Okay Reorganization Of Racetrack". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (January 5, 1963). "Court Confirms Speedway's Plan". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B. 12B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway's Debts Cut By $740,376". The Charlotte Observer. April 2, 1963. pp. 5B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (April 15, 1963). "Goines To Head Raceway". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 9B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wildman, John (November 28, 1990). "Smith Rode Love Of Cars To The Top". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Covington, Roy (February 3, 1974). "After 9 Years, The Boos Changed To Votes". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 6D. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hughes, Bill (December 4, 1963). "Speedway Board Declares Dividend". The Charlotte News. pp. 17A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charlotte Motor Speedway In The Black Now". The Charlotte News. February 11, 1964. pp. 43C. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway Tabs Richard Howard As Acting GM". The Charlotte Observer. April 16, 1964. pp. 28A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Death Of Roberts Stuns Racing". The Charlotte News. July 2, 1964. pp. 6A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lloyd, Harry (October 18, 1965). "Kite Survived Wars, Died At High Speed". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A, 14A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (June 10, 1967). "The Burning Of The Mortgage". The Charlotte News. pp. 4A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Myers, Bob (October 8, 1975). "Track Needs Howard". The Charlotte News. pp. 1C, 4C. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway Acquires Rightway". The Charlotte Observer. September 22, 1965. pp. 1D, 4D. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (January 14, 1970). "Assessment By IRS Cuts Into Profits Of Speedway". The Charlotte News. pp. 14B. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (January 7, 1972). "Speedway's Year Most Profitable". The Charlotte News. pp. 12A. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Covington, Roy (February 3, 1974). "After 9 Years, The Boos Changed To Votes". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 6D. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (May 26, 1973). "Bruton Smith's Return". The Charlotte News. pp. 9A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Covington, Roy (January 31, 1974). "Speedway Election In Doubt". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Covington, Roy (February 1, 1974). "Deposed Speedway Official Regains Spot On Board". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 20A. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Laye, Leonard (May 2, 1974). "Speedway Expansion To Cost $2 Million". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 3B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moore, Bob (January 31, 1975). "Howard Group Regains CMS Control". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 3D. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (February 1, 1975). "The Speedway Shootout". The Charlotte News. pp. 7A, 8A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Covington, Roy (October 12, 1975). "Bruton Smith Simply Outran Speedway's Richard Howard". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 9B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ervin's Wheeler Takes Position at Speedway". The Charlotte News. Associated Press. August 29, 1975. pp. 4C. Retrieved July 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (October 2, 1975). "Howard's Charlotte Reign Appears Over". Winston-Salem Journal. p. 63. Retrieved July 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, Jim (October 5, 1975). "National 500 Race Last for Howard?". The Atlanta Constitution. pp. 10D. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (October 7, 1975). "Howard Report Called Premature". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 3B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (October 23, 1975). "Car Builders May Challenge France's Rule". Winston-Salem Journal. p. 53. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (January 31, 1976). "Wheeler: Speedway's New Dealer". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (May 22, 1976). "Speedway Getting Major Face-Lift". The Charlotte News. pp. 1B, 3B. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ King, Randy (May 27, 1990). "Call him 'Humpy,' the Wheeler dealer". The Roanoke Times. pp. B1, B8, B9. Retrieved July 24, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nixon, Kathy (January 18, 1987). "Message: 'Hang In There'". The Charlotte Observer. p. 192. Retrieved August 2, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (October 6, 1977). "Pearson Edges Allison". Winston-Salem Journal. pp. 51, 58. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hinkle, Jane (February 7, 1980). "Motor Speedway moving soon to new headquarters". The Charlotte News. pp. 9A. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Higgins, Tom; Lohwasser, Don (March 12, 1985). "Speedway plans to develop stadium". The Charlotte News. pp. 1C. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lohwasser, Don (March 14, 1985). "Speedway Would Build, Not Pay For, Stadium". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 4B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Claiborne, Jack (December 9, 1959). "New Grid 'Stadium' Promised". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A. Retrieved February 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b nascarman (September 15, 2016). "Football at Charlotte Motor Speedway". Racing Reference. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Lohwasser, Don (March 17, 1985). "Smith, Shinn Share Football Goals, Not Methods". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sorenson, Tom (October 19, 1987). "NFL Talk Is Not A Laughing Matter". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (October 16, 1991). "PRIME TIME: The Winston Will Be Held Under Lights". Winston-Salem Journal. p. 41. Retrieved August 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (April 16, 1992). "Speedway test is ablaze in glory". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Green Jr., Ron (May 22, 1994). "Indy folks drop in on speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 12G. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Postman, Lore (February 10, 1999). "Lowe's raises its stake in racing". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 6D. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cooper, Ray (January 17, 1989). "Sportsman Division to debut in Charlotte". News & Record. pp. B4, B7. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (May 17, 1990). "Driver Dies in Speedway Accident". Winston-Salem Journal. pp. 34, 37. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Chandler, Charles (May 17, 1992). "Car's path ends again in Charlotte". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 9C. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Clarke, Liz; Higgins, Tom (October 7, 1995). "Tragedy at the race track". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 8A. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b nascarman (October 6, 2016). "The History of the NASCAR Sportsman Division". Racing Reference. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Green Jr., Ron (November 29, 1995). "Speedway will pass on Sportsman races". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Green Jr., Ron (May 2, 1999). "3 race fans killed, 8 hurt by flying tire, debris". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 18A. Retrieved July 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Alexander, Ames; Chandler, Liz; Cimino, Karen; Dodd, Scott; Frazier, Eric; Henderson, Bruce; Johnson, Mark; Moore, Robert F.; Paynter, Marion; St. Onge, Courtney (May 22, 2000). "Corroded cables draw investigator's attention". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 6A. Retrieved July 27, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whitmare, Tim (March 21, 2003). "Couple awarded $4 million". The Herald-Sun. Associated Press. pp. B8. Retrieved July 30, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marusak, Joe (March 16, 2018). "Bridge collapse revives memories of 'horrible night' at Charlotte speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A. Retrieved July 30, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David; Utter, Him; Wolken, Dan (October 5, 2001). "ARCA race ends with death". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 6C. Retrieved February 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Utter, Jim (October 10, 2002). "Race driver killed in speedway wreck". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 9A. Retrieved February 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David (March 12, 2005). "Wheeler: Smoothing of track finished". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5C. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newton, David (October 14, 2005). "Magical Humpy". The State. pp. C3, C12. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newton, David (July 12, 2011). "NASCAR: Five embarrassing moments". ESPN. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (September 29, 2007). "Work continues at drag strip site". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (October 2, 2007). "Council orders halt to work on drag strip". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Zeller, Bob (October 13, 1991). "Speedway owner lives in fast lane". News & Record. pp. C1, C2. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Utter, Jim (May 19, 2010). "Wheeler: Increasing secrecy led to his exit". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 7C. Retrieved July 30, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Poole, David (May 21, 2008). "Checkered Flag For 'Humpy'". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 8A. Retrieved July 30, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newton, David (May 21, 2008). "Humpy Wheeler kicked out before his time was really up". ESPN. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ Bonkowski, Jerry (May 21, 2008). "Humpy's sad farewell". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ Poole, David (May 29, 2008). "Smith picks son to lead speedway, firm". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 2D. Retrieved January 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valle, Kirsten (August 7, 2009). "Concord track will be renamed – but what?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 4D. Retrieved January 12, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Janes, Théoden (August 13, 2017). "The true story behind the fictional movie about the Charlotte Motor Speedway heist". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 2C. Retrieved February 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Spanberg, Erik (September 13, 2019). "How he's building Charlotte Motor Speedway for the future". Charlotte Business Journal. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Davison, Drew (October 1, 2020). "Texas Motor Speedway to host NASCAR All-Star Race in 2021". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. pp. 1B, 3B. Retrieved January 19, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fowler, Scott (May 11, 2011). "Speedway's hi-def TV a def must-see". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 2C. Retrieved January 12, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Person, Joesph (May 24, 2015). "Charlotte adding safety measures". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ackley, J. A. (April 19, 2023). "Plans for a new road course at Charlotte Motor Speedway". Grassroots Motorsports. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Crissman, Bob (August 23, 1959). "Turner Visualizes 'World 600' Race". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 8D. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Einstein, Tom (September 17, 1959). "Lee Petty Shrugs Off 500 Showing... Has Big Week". News & Record. pp. B11. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "May 29 Scheduled For Speedway Opener". The Charlotte Observer. September 23, 1959. pp. 5B. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Einstein, Tom (June 19, 1960). "Grueling World 600 Set At Charlotte Speedway Today". News & Record. pp. B2, B5. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (June 19, 1960). "600 Reality Today, If Track Holds". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Retrieved February 2, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lipowski, Joshua (May 22, 2023). "NASCAR's Crown Jewel Events: What Are They, and Which Ones Can be Added?". The Daily Downforce. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Ken (May 27, 2021). "How the Coca-Cola 600 became a crown jewel event for NASCAR". NASCAR. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Cunningham, Geroge (June 29, 1960). "Speedway Slates October 400-Miler". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moore, Bob (December 19, 1965). "National 400 Race Goes To 500 Miles". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 4D. Retrieved February 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Utter, Jim (July 4, 2018). "NASCAR Cup race on Charlotte Roval to see length reduced". Motorsport.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ Fryer, Jenna (October 4, 2018). "'Roval' a smashing success for all except Johnson". Austin American-Statesman. Associated Press. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (January 15, 1985). "Charlotte To Host $500,000 Race". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 3B, 4B. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pearce, Al (May 18, 2023). "NASCAR All-Star Race Format, History, And What's Right (And Wrong) With All-Star Concept". Autoweek. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Armstrong, Megan (June 15, 2020). "2020 NASCAR All-Star Race Moved to Bristol Motor Speedway; 30K Fans Permitted". Bleacher Report. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Miller, Robin (December 27, 1979). "USAC Announces 1980 Schedule". The Indianapolis Star. p. 31. Retrieved June 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Champ' Race Cancelled". The Charlotte Observer. April 23, 1980. pp. 4B. Retrieved February 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bonnell, Rick (December 15, 1996). "Charlotte to stage IRL race on July 26". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1G. Retrieved August 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Utter, Jim (April 2, 2000). "Panoz makes run at BMW". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 11H. Retrieved February 6, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ryan, Nate (October 10, 2020). "Corvette duo of Antonio Garcia and Jordan Taylor win again at Charlotte Roval". NBC Sports. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Eichel, Henry (August 11, 1974). "Thousands Jam Rock Fest". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 12A. Retrieved February 1, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Domecq, Cailyn (March 7, 2022). "Woodstock, part 2? Fans remember massive rock concert at Charlotte Motor Speedway". The Charlotte Observer. UNC Media Hub. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Sifford, Darrell (August 15, 1974). "Rock Violence". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 6A. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hahne, Jeff (February 1, 2013). "Carolina Rebellion music festival announces 2013 lineup". Creative Loafing Charlotte. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "'Epicenter Festival' To Replace 'Carolina Rebellion' In 2019". The PRP. November 30, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Desmond, Colin (October 4, 2021). "FESTIVAL HIGHLIGHTS: Breakaway Charlotte 2021 Lights Up the Speedway". Tuned Magazine. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Korynta, Emma (January 18, 2024). "Breakaway Presents: Another World coming to the Charlotte Motor Speedway". WCNC-TV. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Blackmon, Chyna (January 25, 2024). "1 weekend. 3 music festivals. How will Lovin' Life Music Fest in Charlotte compare?". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Marusak, Joe (September 17, 2010). "Christmas lights to shine at speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10A, 11A. Retrieved January 12, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Graduations Held at Charlotte Motor Speedway". Spectrum News 1 North Carolina. June 13, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Charlotte Motor Speedway - Racing Circuits". Racingcircuits.info. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Charlotte - Motorsport Database". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Trans Am Series Presented by Pirelli March 17 - 20 2022 Charlotte Motor Speedway TA XGT SGT GT Round 2 Official TA / GT Race Results" (PDF). March 20, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR Cup 2022 Bank of America Roval 400 Race Statistics". October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR Xfinity 2022 Bank of America Drive for the Cure 250 Race Statistics". October 8, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "2020 MOTUL 100% Synthetic Grand Prix Race Official Results (1 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). October 11, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR Cup 2018 Charlotte II Fastest Laps". September 30, 2018. Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR XFINITY 2018 Charlotte II Fastest Laps". September 29, 2018. Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "1998 VisionAire 500K". July 25, 1998. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR Cup 2017 Charlotte Fastest Laps". May 28, 2017. Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "NASCAR XFINITY 2020 Charlotte Fastest Laps". May 25, 2020. Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "2023 North Carolina Education Lottery 200 Race Statistics". May 26, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c "2000 Grand Prix of Charlotte". April 1, 2000. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Charlotte 500 Kilometres 1984". May 20, 1984. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Can-Am Charlotte 1978". May 28, 1978. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Charlotte 300 Kilometres IMSA GTO 1985". May 19, 1985. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Charlotte 500 Kilometres 1985". May 19, 1985. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Charlotte 300 Miles 1974". May 18, 1974. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Trans-Am Charlotte 1981". May 17, 1981. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2024.