| Part of a series on |

| Islamization |

|---|

|

The Islamization of the Sudan region (Sahel)[1] encompasses a prolonged period of religious conversion, through military conquest and trade relations, spanning the 8th to 16th centuries.

Following the 7th century Muslim conquest of Egypt and the 8th-century Muslim conquest of North Africa, Arab Muslims began leading trade expeditions into Sub-Saharan Africa, first towards Nubia, and later across the Sahara into West Africa. Much of this contact was motivated by interest in trans-Saharan trade, particularly the slave trade.

The proliferation of Islamic influence was largely a gradual process. The Christian kingdoms of Nubia were the first to experience Arab incursion starting in the 7th century. They held out through the Middle Ages until the Kingdom of Makuria and Old Dongola both collapsed in the early 14th century. Sufi orders played a significant role in the spread of Islam from the 9th to 14th centuries, and they proselytized across trade routes between North Africa and the sub-Saharan kingdom of Mali. They were also responsible for setting up zawiyas on the shores of the River Niger.

The Mali Empire underwent a period of internally motivated conversion following the 1324 pilgrimage of Musa I of Mali. Subsequently Timbuktu became one of the most important Islamic cultural centers in the Sahara. Alodia, the last holdout of Christian Nubia, was destroyed by the Funj Sultanate in 1504. During the 19th century the Sanusi order was highly involved in missionary work with their missions focused on the spread of both Islam and textual literacy as far south as Lake Chad.[2][3]

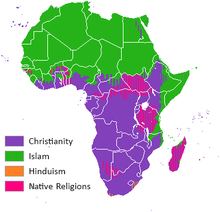

Consequently, much of the contemporary Sudan region is Muslim. This includes the Republic of Sudan (after the secession of Christian-majority South Sudan), the northern parts of Chad and Niger, most of Mali, Mauritania and Senegal. The problem of slavery in contemporary Africa remains especially pronounced in these countries, with severe divides between the Arabized population of the north and dark-skinned Africans in the south motivating much of the conflict, as these nations sustain the centuries-old pattern of hereditary servitude that arose following early Muslim conquests.[4] Ethnic strife between Arabized and non-Arab black populations has led to various internal conflicts in the Sudan region, most notably the War in Darfur, the Northern Mali conflict, and the Islamist insurgency in Northern Nigeria.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/3Views:2 567 5981 195932

-

Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

-

Maghreb

-

Conversations in the Commons with Peter Beinart: Islam in America

Transcription

Hi there, my name’s John Green, this is Crash Course World History and today we’re gonna talk about Africa. Mr. Green Mr. Green! We’ve already been talking about Africa. Egypt is in Africa, and you haven’t shut up about it the entire course— Yeah that’s true, Me from the Past. But Africa’s big— it’s like, super big— much bigger than it appears on most maps, actually. I mean, you can fit India and China, and the United States if you fold in Maine. All of that fits in Africa. Like any huge place, Africa is incredibly diverse, and its a mistake to focus just on Egypt. So today let’s go here, south of the Sahara desert. [music intro] [music intro] [music intro] [music intro] [music intro] [music intro] First, let’s turn to written record. Oh, right. We don’t have very many. At least not written by Sub-Saharan Africans. Much of African history was preserved via oral rather than written tradition. These days, we tend to think of writing as the most accurate and reliable form of description, but then again we do live in a print-based culture. And we’ve already said that writing is one of the markers of civilization, implying that people who don’t use writing aren’t civilized, a prejudice that has been applied over and over again to Africa. But 1. if you need any evidence that it’s possible to produce amazing literary artifacts without the benefits of writing, let me direct your attention to the Iliad and the Odyssey, which were composed and memorized by poets for centuries before anyone ever wrote them down. And 2. No less an authority than Plato said that writing destroys human memory by alleviating the need to remember anything. And 3. You think the oral tradition is uncivilized but HERE YOU ARE LISTENING TO ME TALK. But we do have a lot of interesting records for some African histories, including the legendary tale of Mansa Musa. By legendary I mean some of it probably isn’t true, but it sure is important. Let’s go to the Thought Bubble. So there was this king Mansa Musa, who ruled the west African empire of Mali, and in 1324ish he left his home and made the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca. He brought with him an entourage of over 1000 (some sources say 60,000) and, most importantly, 100 camel loads of gold. I wish it had been donkeys so I could say he had 100 assloads of gold, but no. Camels. Right, so along the way Mansa Musa spent freely and gave away lots of his riches. Most famously, when he reached Alexandria, at the time one of the most cultured cities in the world, he spent so much gold that he caused runaway inflation throughout the city that took years to recover from. He built houses in Cairo and in Mecca to house his attendants, and as he traveled through the world, a lot of people— notably the merchants of Venice— no, Thought Bubble, like actual merchants of Venice— right. They saw him in Alexandria and returned to Italy with tales of Mansa Musa’s ridiculous wealth, which helped create the myth in the minds of Europeans that West Africa was a land of gold, an El Dorado. The kind of place you’d like to visit. And maybe, you know, in five centuries or so, begin to pillage. Thanks Thought Bubble. So what’s so important about the story of Mansa Musa? Well, first, it tells us there were African kingdoms, ruled by fabulously wealthy African kings. Which undermines one of the many stereotypes about Africa, that its people were poor and lived in tribes ruled by chiefs and witch doctors. Also, since Mansa Musa was making the hajj, we know that he was A. Muslim and B. relatively devout. And this tells us that Africa, at least western Africa, was much more connected to the parts of the world we’ve been talking about than we generally are led to believe. Mansa Musa knew all about the places he was going before he got there, and after his visits, the rest of the Mediterranean world was sure interested in finding out more about his homeland. Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage also brings up a lot of questions about west Africa, namely, what did his kingdom look like and how did he come to convert to Islam? The first question is a little easier, so we’ll start with that one. The empire of Mali, which Mansa Musa ruled until the extremely elite year of 1337, was a large swath of West Africa, running from the coast hundreds of miles into the interior and including many significant cities, the largest and best-known of which was Timbuktu. The story of the Islamization of the Empire, however, is a bit more complicated. Okay, so pastoral North Africans called Berbers had long traded with West Africans, with the Berbers offering salt in exchange for West African gold. That may seem like a bad deal until you consider that without salt, we die, whereas without gold, we only have to face the universe’s depraved indifference to us without the benefit of metallic adornment. That went to an ominous place quickly. Right, so anyway the Berbers were early converts to Islam, and Islam spread along those pre-existing trade routes between North and West Africa. Right, so the first converts in Mali were traders, who benefited from having a religious as well as commercial connection to their trading partners in the North and the rest of the Mediterranean. And then the kings followed the traders, maybe because sharing the religion of more established kingdoms in the north and east would give them prestige, not to mention access to scholars and administrators who could help them cement their power. So Islam became the religion of the elites in West Africa, which meant that the Muslim kings were trying to extend their power over largely non-Muslim populations that worshipped traditional African gods and spirits. In order not to seem too foreign, these African Muslim kings would often blend traditional religion with Islam. For instance, giving women more equality than was seen in Islam’s birthplace. Anyway, the first kings we have a record of adopting Islam were from Ghana, which was the first “empire” in western Africa. It really took off in the 11th century. As with all empires, and also everything else, Ghana rose and then fell, and it was replaced by Mali. The kings of Mali, especially Mansa Musa but also Mansa Sulayman his successor, tried to increase the knowledge and practice of Islam in their territory. So for example, when Mansa Musa returned from his hajj, he brought back scholars and architects to build mosques. And the reason we know a lot about Mali is because it was visited by Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan cleric and scholar who kinda had the best life ever. He was particularly fascinated by gender roles in the Malian empire— and by Malian women— writing: “They are extremely beautiful, and more important than the men.” Oh. It must be time for the open letter. [rolls with wild, reckless abandon to the caged inferno] An Open Letter to Ibn Battuta: I wonder what’s in the Secret Compartment today. Oh. I appears to be some kind of fake beard... [a hirsute wish is made] Movie magic! [John = L4D Bill] Stan, why did you do this to me? Dear Ibn Battuta, Bro, I love twitter and my x-box and Hawaiian pizza, but if I had to go into the past and live anyone’s life, it would be yours! Because you were this outlandishly learned scholar who managed to parlay your knowledge of Islam into the greatest road trip in history. You went from Mali to Constantinople to India to Russia to Indonesia; you were probably the most widely traveled person before the invention of the steam engine. And everywhere you went, you were treated like a king and then you went home and wrote a really famous book called the Rihla, which people still read today and also you could grow a real beard and I'M JEALOUS! Best wishes, John Green That was a great open letter. Not to brag er anything, but you know, it was. One more thing about Mansa Musa: There are lots of stories that Mansa Musa attempted to engage in maritime trade across the Atlantic Ocean, and some historians even believe that Malians reached the Americas. DNA investigation may one day prove it, but until then, we’ll only have oral tradition. The Malian Empire eventually fell to the Songhay, which was eventually overthrown for being insufficiently Islamic, meaning that centuries after his death Mansa Musa had succeeded at bringing Islamic piety to his people. All of which is to say that— like China or India or Europe— West Africa had its own empires that relied upon religion and war and incredibly boring dynastic politics. Man, I hate dynastic politics. If I wanted to live in an ostensibly independent country that can’t let go of Monarchy, I’d be like Thought Bubble and move to Canada. Oh, come on, Thought Bubble- that’s not fair. Shut up and take back Celine Dion! Alright, now let’s move to the other side of Africa where there was an alternative model of “civilizational” development. The eastern coast of Africa saw the rise of what historians called the Swahili civilization, which was not an empire or a kingdom but a collection of city states— like Zanzibar and Mombasa and Mogadishu-- — All of which formed a network of trade ports. There was no central authority – each of these cities was autonomous ruled, usually, but not always, by a king. But there were three things that linked these city states such that we can consider them a common culture: language, trade and religion. The Swahili language is part of a language group called Bantu, and its original speakers were from West Africa. Their migration to East Africa not only changed the linguistic traditions of Africa but everything else, because they brought with them iron work and agriculture. Until then, most of the people living in the East had been hunter gatherers or herders, but once introduced, agriculture took hold as it almost always does. Unless, wait for it-- --you’re the Mongols. [Mongol-tage horns sound] Modern day Swahili, by the way, is still a Bantu based language, although it’s been heavily influenced by Arabic. On that topic: For a long time historians believed that the East African cities were all started by Arab or Persian traders, which was basically just racist: they didn’t believe that Africans were sophisticated enough to found these great cities, like Mogadishu and Mombasa. Now scholars recognize that all the major Swahili cities were founded well before Islam arrived in the region and then in fact trade had been going on since the first century CE. But Swahili civilization didn’t begin its rapid development until the 8th century when Arab traders arrived seeking goods that they could trade in the vast Indian Ocean network, the Silk Road of the sea. And of course those merchants brought Islam with them, which, just like in West Africa was adopted by the elites who wanted religious as well as commercial connections to the rest of the Mediterranean world. In many of the Swahili states these Muslim communities started out quite small, but at their height between the 13th and 16th century most of the cities boasted large mosques. The one in Kilwa even impressed Ibn Battuta, who of course visited the city, because he was having the best life ever. Most of the goods exported were raw materials, like ivory, animal hides and timber— it’s worth noting, by the way, that when you’re moving trees around, you have a level of sophistication to your trade that goes way beyond the Silk Road. I mean, if you’ll recall they weren’t just trading tortoise shells and stuff--- [Pouf-dodges with cat-like agility] Not again! Africans also exported slaves along the east coast, although not in HUGE numbers, and they exported gold, and they imported finished luxury goods like porcelain and books. In fact, archaeological digs in Kilwa have revealed that houses often featured a kind of built-in bookshelf. Learning of books through architecture nicely captures the magic of studying history. Archaeology, writing, and oral tradition all intermingle to give us glimpses of the past. And each of those lenses may show us the past as if through some funhouse mirror, but if we’re conscious about it, we can at least recognize the distortions. Studying Africa reminds us that we need to look at lots of sources, and lots of kinds of sources if we want to get a fuller picture of the past. If we relied on only written sources, it would be far too easy to fall into the old trap of seeing Africa as backwards and uncivilized. Through approaching it with multiple lenses, we discover a complicated, diverse place that was sometimes rich and sometimes not— and when you think of it that way, it becomes not separate from, but part of, our history. Thanks for watching. We’ll see you next week. CrashCourse is produced and directed by Stan Muller, Our script supervisor is Danica Johnson, The show is written by my high school history teacher Raoul Meyer and myself And our Graphics Team is ThoughtBubble [Perhaps hanging at the Hoser Hut?] Last week's Phrase Of The Week was Animal Crackers If you want to suggest future phrases of the week or guess at this one, you can do so in comments Also, if you have questions about today's video Ask them, and our team of historians will endeavor to answer them. Thanks for watching and supporting CrashCourse And as we say in my hometown, Don't forget there's always money in the Banana Stand.

The Arabs

Contacts between Nubians and Arabs long predated the coming of Islam,[5] but the Arabization of the Nile Valley was a gradual process that occurred over a period of nearly one thousand years. Arab nomads continually wandered into the region in search of fresh pasturage, and Arab seafarers and merchants traded at Red Sea ports for spices and slaves. Intermarriage and assimilation also facilitated Arabization. After the initial attempts at military conquest failed, the Arab commander in Egypt, Abd Allah ibn Saad, concluded the first in a series of regularly renewed treaties with the Nubians that governed relations between the two peoples for more than six hundred years with only brief interruptions.[6] This treaty was known as the Baqt. Relations between Egypt and Nubia were peaceful whilst Egypt was under Arabian control with tensions arising whilst the Mamluks were in power in Egypt.

The Arabs realized the commercial advantages of peaceful relations with Nubia and used the Baqt to ensure that travel and trade proceeded unhindered across the frontier. The Baqt also contained security arrangements whereby both parties agreed that neither would come to the defense of the other in the event of an attack by a third party. The Baqt obliged both to exchange annual tribute as a goodwill symbol: the Nubians sent slaves and the Arabs sent grain. This formality was only a token of the trade that developed between the two. It was not only a trade in slaves and grain but also in horses and manufactured goods brought to Nubia by the Arabs, and in ivory, gold, gems, gum arabic, and cattle carried back by them to Egypt, or shipped to Arabia.

Acceptance of the Baqt did not indicate Nubian submission to the Arabs; however, the treaty did impose conditions for Arab friendship that eventually permitted Arabs to achieve a privileged position in Nubia. Arab merchants established markets in Nubian towns to facilitate the exchange of grain and slaves. Arab engineers supervised the operation of mines east of the Nile in which they used slave labor to extract gold and emeralds. Muslim pilgrims en route to Mecca traveled across the Red Sea on ferries from Aydhab and Suakin, ports that also received cargoes bound from India to Egypt.

Traditional genealogies trace the ancestry of the Nile Valley's mixed population to Arab tribes that migrated into the region during this period. Even many non-Arabic-speaking groups claim descent from Arab forebears. The two most important Arabic-speaking groups to emerge in Nubia were the Ja'alin and the Juhaynah. Both showed physical continuity with the indigenous pre-Islamic population. The former claimed descent from the Quraysh, the Prophet Muhammad's tribe. Historically, the Ja'ali have been involved in the slave trade, making up an important subsection of the nomadic, slave trading jallaba, along with other tribes such as the Danagla.[7] The nomadic Juhayna comprised a family of tribes that included the Kababish, Baqqara, and Shukriya. They were descended from Arabs who migrated after the 13th century into an area that extended from the savanna and semi-desert west of the Nile to the Abyssinian foothills east of the Blue Nile. Both groups formed a series of tribal shaykhdoms that succeeded the crumbling Christian Nubian kingdoms, and were in frequent conflict with one another and with neighboring non-Arabs. In some instances, such as with the Beja, the indigenous people absorbed Arab migrants who settled among them. Beja ruling families later derived their legitimacy from their claims of Arab ancestry.

Although not all Muslims in the region were Arabic-speaking, acceptance of Islam facilitated the Arabization process. There was no policy of proselytism, however. Islam penetrated the area over a long period of time through intermarriage and contacts with Arab merchants and settlers.[8]

The Funj

| History of Sudan | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Before 1956 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Since 1955 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| By region | ||||||||||||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

At the same time that the Ottomans brought northern Nubia into their orbit, a new power, the Funj, had risen in southern Nubia and had supplanted the remnants of the old Christian Kingdom of Alodia. In 1504 a Funj leader, Amara Dunqas, founded the Kingdom of Sennar. This Sultanate eventually became the keystone of the Funj Empire. By the mid-sixteenth century, Sennar controlled Al Jazirah and commanded the allegiance of vassal states and tribal districts as far north as the third cataract of the nile and as far south as the rainforests.

The Funj state included a loose confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal chieftains drawn together under the suzerainty of Sennar's mek (sultan). As overlord, the mek received tribute, levied taxes, and called on his vassals to supply troops in times of war. Vassal states in turn relied on the mek to settle local disorders and to resolve internal disputes. The Funj stabilized the region and interposed a military bloc between the Arabs in the north, the Abyssinians in the east, and the non-Muslim blacks in the south.

The sultanate's economy depended on the role played by the Funj in the slave trade. Farming and herding also thrived in Al Jazirah and in the southern rainforests. Sennar apportioned tributary areas into tribal homelands each one termed a dar (pl., dur), where the mek granted the local population the right to use arable land. The diverse groups that inhabited each dar eventually regarded themselves as units of tribes. Movement from one dar to another entailed a change in tribal identification. (Tribal distinctions in these areas in modern Sudan can be traced to this period.) The mek appointed a chieftain (nazir; pl., nawazir) to govern each dar. Nawazir administered dur according to customary law, paid tribute to the mek, and collected taxes. The mek also derived income from crown lands set aside for his use in each dar.

At the peak of its power in the mid-17th century, Sennar repulsed the northward advance of the Nilotic Shilluk people up the White Nile and compelled many of them to submit to Funj authority. After this victory, the mek Badi II Abu Duqn (1642–81) sought to centralize the government of the confederacy of Sennar. To implement this policy, Badi introduced a standing army of slave soldiers that would free Sennar from dependence on vassal sultans for military assistance, and would provide the mek with the means to enforce his will. The move alienated the dynasty from the Funj warrior aristocracy which deposed the reigning mek, and placed one of their own ranks on the throne of Sennar in 1718. The mid-18th century witnessed another brief period of expansion when the Funj turned back an Abyssinian invasion, defeated the Fur, and took control of much of Kurdufan. But the civil war, and the demands of defending the sultanate, had overextended the warrior society's resources and sapped its strength.

Another reason for Sennar's decline may have been the growing influence of its hereditary viziers (chancellors), chiefs of a non-Funj tributary tribe who managed court affairs. In 1761, the vizier Muhammad Abu al Kaylak, who had led the Funj army in wars, carried out a palace coup, relegating the sultan to a figurehead role. Sennar's hold over its vassals diminished, and by the early 19th century, more remote areas ceased to recognize even the nominal authority of the mek.

The Fur

Darfur was the Fur homeland. Renowned as cavalrymen,[9] Fur clans frequently allied with, or opposed their kin, the Kanuri of Borno, in modern Nigeria. After a period of disorder in the sixteenth century, during which the region was briefly subject to the Bornu Empire, the leader of the Keira clan, Sulayman Solong (1596–1637), supplanted a rival clan and became Darfur's first sultan. Sulayman Solong decreed Islam to be the sultanate's official religion. However, large-scale religious conversions did not occur until the reign of Ahmad Bakr (1682–1722), who imported teachers, built mosques, and compelled his subjects to become Muslims. In the eighteenth century, several sultans consolidated the dynasty's hold on Darfur, established a capital at Al-Fashir, and contested the Funj for control of Kurdufan.

The sultans operated the slave trade as a monopoly. They levied taxes on traders, and export duties on slaves sent to Egypt, and took a share of the slaves brought into Darfur. Some household slaves advanced to prominent positions in the courts of sultans, and the power exercised by these slaves provoked a violent reaction among the traditional class of Fur officeholders in the late eighteenth century. The rivalry between the slave and traditional elites caused recurrent unrest throughout the next century.

See also

References

- ^ The "Sudan region" encompasses not just the history of the Republic of Sudan (whose borders are those of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, drawn in 1899) but of the wider Sahel, in Arabic known as bilad as-sudan, "the land of the blacks".

- ^ Holt, Peter M.; Daly, Martin W. (1971). History of the Sudan: From the Coming Islam to the present day. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1138432192.

- ^ Duta, Paul; Ungureanu, Roxelana (November 2016). "The Sudanese civil war – the effect of arabisation and islamisation". Research and Science Today. 2 (12): 50–59. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

Islam has been introduced in Sudan by several religious orders, each with their own interpretations and dogmas, being able to talk about different sects (tariqa), the Muslim Brotherhood corresponding the schools of Muslim thinking. Each Muslim cult has its own structure, leader, space and after independence from Anglo-Egyptian condominium it has its own political party. The multitude of sects and the differences between them do not permit to speak of a Muslim community; over time, the differences between these sects have generated conflicts, fighting against each other allowing the British and Egyptians to successfully apply the adage 'divide at impera.'

- ^ "The mobilization of local ideas about racial difference has been important in generating, and intensifying, civil wars that have occurred since the end of colonial rule in all of the countries that straddle the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. [...] contemporary conflicts often hearken back to an older history in which blackness could be equated with slavery and non-blackness with predatory and uncivilized banditry." (cover text), Hall, Bruce S., A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- ^ "INTRODUCTION", Arabia and the Arabs, Routledge, pp. 13–24, 2002-09-11, doi:10.4324/9780203455685-4, ISBN 978-0-203-45568-5, retrieved 2023-07-04

- ^ Hoyland, Robert (2015). In God's Path: The Arab Conquest and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 77.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2004). The Sword of the Prophet. Sutton: Gloucester. p. 55.

- ^ "East Meets West", The Archaeology of Malta, Cambridge University Press, pp. 171–217, 2015-08-25, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139030465.007, ISBN 978-1-139-03046-5, retrieved 2023-07-04

- ^ Minahan, James B. (30 May 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World A-Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 625. ISBN 9780313076961. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

Further reading

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – Sudan

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – Sudan- Spencer Trimingham, History of Islam in West Africa. Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels (eds). The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press, 2000.

- David Robinson. Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Bruce S. Hall, A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 9781107002876.

External links

- Trade and the Spread of Islam in Africa, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2001).