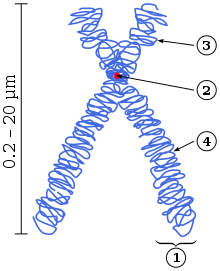

A chromatid (Greek khrōmat- 'color' + -id) is one half of a duplicated chromosome. Before replication, one chromosome is composed of one DNA molecule. In replication, the DNA molecule is copied, and the two molecules are known as chromatids.[1] During the later stages of cell division these chromatids separate longitudinally to become individual chromosomes.[2]

Chromatid pairs are normally genetically identical, and said to be homozygous. However, if mutations occur, they will present slight differences, in which case they are heterozygous. The pairing of chromatids should not be confused with the ploidy of an organism, which is the number of homologous versions of a chromosome.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/3Views:1 124 233112 959364 874

-

Chromosomes, Chromatids, Chromatin, etc.

-

Chromosome chromatin and chromatid

-

Chromosome Numbers During Division: Demystified!

Transcription

Before I dive into the mechanics of how cells divide, I think it could be useful to talk a little bit about a lot of the vocabulary that surrounds DNA. There's a lot of words and some of them kind of sound like each other, but they can be very confusing. So the first few I'd like to talk about is just about how DNA either generates more DNA, makes copies of itself, or how it essentially makes proteins, and we've talked about this in the DNA video. So let's say I have a little-- I'm just going to draw a small section of DNA. I have an A, a G, a T, let's say I have two T's and then I have two C's. Just some small section. It keeps going. And, of course, it's a double helix. It has its corresponding bases. Let me do that in this color. So A corresponds to T, G with C, it forms hydrogen bonds with C, T with A, T with A, C with G, C with G. And then, of course, it just keeps going on in that direction. So there's a couple of different processes that this DNA has to do. One is when you're just dealing with your body cells and you need to make more versions of your skin cells, your DNA has to copy itself, and this process is called replication. You're replicating the DNA. So let me do replication. So how can this DNA copy itself? And this is one of the beautiful things about how DNA is structured. Replication. So I'm doing a gross oversimplification, but the idea is these two strands separate, and it doesn't happen on its own. It's facilitated by a bunch of proteins and enzymes, but I'll talk about the details of the microbiology in a future video. So these guys separate from each other. Let me put it up here. They separate from each other. Let me take the other guy. Too big. That guy looks something like that. They separate from each other, and then once they've separated from each other, what could happen? Let me delete some of that stuff over here. Delete that stuff right there. So you have this double helix. They were all connected. They're base pairs. Now, they separate from each other. Now once they separate, what can each of these do? They can now become the template for each other. If this guy is sitting by himself, now all of a sudden, a thymine base might come and join right here, so these nucleotides will start lining up. So you'll have a thymine and a cytosine, and then an adenine, adenine, guanine, guanine, and it'll keep happening. And then on this other part, this other green strand that was formerly attached to this blue strand, the same thing will happen. You have an adenine, a guanine, thymine, thymine, cytosine, cytosine. So what just happened? By separating and then just attracting their complementary bases, we just duplicated this molecule, right? We'll do the microbiology of it in the future, but this is just to get the idea. This is how the DNA makes copies of itself. And especially when we talk about mitosis and meiosis, I might say, oh, this is the stage where the replication has occurred. Now, the other thing that you'll hear a lot, and I talked about this in the DNA video, is transcription. In the DNA video, I didn't focus much on how does DNA duplicate itself, but one of the beautiful things about this double helix design is it really is that easy to duplicate itself. You just split the two strips, the two helices, and then they essentially become a template for the other one, and then you have a duplicate. Now, transcription is what needs to occur for this DNA eventually to turn into proteins, but transcription is the intermediate step. It's the step where you go from DNA to mRNA. And then that mRNA leaves the nucleus of the cell and goes out to the ribosomes, and I'll talk about that in a second. So we can do the same thing. So this guy, once again during transcription, will also split apart. So that was one split there and then the other split is right there. And actually, maybe it makes more sense just to do one-half of it, so let me delete that. Let's say that we're just going to transcribe the green side right here. Let me erase all this stuff right-- nope, wrong color. Let me erase this stuff right here. Now, what happens is instead of having deoxyribonucleic acid nucleotides pair up with this DNA strand, you have ribonucleic acid, or RNA pair up with this. And I'll do RNA in magneta. So the RNA will pair up with it. And so thymine on the DNA side will pair up with adenine. Guanine, now, when we talk about RNA, instead of thymine, we have uracil, uracil, cytosine, cytosine, and it just keeps going. This is mRNA. Now, this separates. That mRNA separates, and it leaves the nucleus. It leaves the nucleus, and then you have translation. That is going from the mRNA to-- you remember in the DNA video, I had the little tRNA. The transfer RNA were kind of the trucks that drove up the amino acids to the mRNA, and this all occurs inside these parts of the cell called the ribosome. But the translation is essentially going from the mRNA to the proteins, and we saw how that happened. You have this guy-- let me make a copy here. Let me actually copy the whole thing. This guy separates, leaves the nucleus, and then you had those little tRNA trucks that essentially drive up. So maybe I have some tRNA. Let's see, adenine, adenine, guanine, and guanine. This is tRNA. That's a codon. A codon has three base pairs, and attached to it, it has some amino acid. And then you have some other piece of tRNA. Let's say it's a uracil, cytosine, adenine. And attached to that, it has a different amino acid. Then the amino acids attach to each other, and then they form this long chain of amino acids, which is a protein, and the proteins form these weird and complicated shapes. So just to kind of make sure you understand, so if we start with DNA, and we're essentially making copies of DNA, this is replication. You're replicating the DNA. Now, if you're starting with DNA and you are creating mRNA from the DNA template, this is transcription. You are transcribing the information from one form to another: transcription. Now, when the mRNA leaves the nucleus of the cell, and I've talked-- well, let me just draw a cell just to hit the point home, if this is a whole cell, and we'll do the structure of a cell in the future. If that's the whole cell, the nucleus is the center. That's where all the DNA is sitting in there, and all of the replication and the transcription occurs in here, but then the mRNA leaves the cell, and then inside the ribosomes, which we'll talk about more in the future, you have translation occur and the proteins get formed. So mRNA to protein is translation. You're translating from the genetic code, so to speak, to the protein code. So this is translation. So these are just good words to make sure you get clear and make sure you're using the right word when you're talking about the different processes. Now, the other part of the vocabulary of DNA, which, when I first learned it, I found tremendously confusing, are the words chromosome. I'll write them down here because you can already appreciate how confusing they are: chromosome, chromatin and chromatid. So a chromosome, we already talked about. You can have DNA. You can have a strand of DNA. That's a double helix. This strand, if I were to zoom in, is actually two different helices, and, of course, they have their base pairs joined up. I'll just draw some base pairs joined up like that. So I want to be clear, when I draw this little green line here, it's actually a double helix. Now, that double helix gets wrapped around proteins that are called histones. So let's say it gets wrapped like there, and it gets wrapped around like that, and it gets wrapped around like that, and you have here these things called histones, which are these proteins. Now, this structure, when you talk about the DNA in combination with the proteins that kind of give it structure and then these proteins are actually wrapped around more and more, and eventually, depending on what stage we are in the cell's life, you have different structures. But when you talk about the nucleic acid, which is the DNA, and you combine that with the proteins, you're talking about the chromatin. So this is DNA plus-- you can view it as structural proteins that give the DNA its shape. And the idea, chromatin was first used-- because when people look at a cell, every time I've drawn these cell nucleuses so far, I've drawn these very well defined-- I'll use the word. So let's say this is a cell's nucleus. I've been drawing very well-defined structures here. So that's one, and then this could be another one, maybe it's shorter, and then it has its homologous chromosome. So I've been drawing these chromosomes, right? And each of these chromosomes I did in the last video are essentially these long structures of DNA, long chains of DNA kind of wrapped tightly around each other. So when I drew it like that, if we zoomed in, you'd see one strand and it's really just wrapped around itself like this. And then its homologous chromosome-- and remember, in the variation video, I talked about the homologous chromosome that essentially codes for the same genes but has a different version. If the blue came from the dad, the red came from the mom, but it's coding for essentially the same genes. So when we talk about this one chain, let's say this one chain that I got from my dad of DNA in this structure, we refer to that as a chromosome. Now, if we refer generally-- and I want to be clear here. DNA only takes this shape at certain stages of its life when it's actually replicating itself-- not when it's replicating. Before the cell can divide, DNA takes this very well-defined shape. Most of the cell's life, when the DNA is actually doing its work, when it's actually creating proteins or proteins are being essentially transcribed and translated from the DNA, the DNA isn't all bundled up like this. Because if it was bundled up like, it would be very hard for the replication and the transcription machinery to get onto the DNA and make the proteins and do whatever else. Normally, DNA-- let me draw that same nucleus. Normally, you can't even see it with a normal light microscope. It's so thin that the DNA strand is just completely separated around the cell. I'm drawing it here so you can try to-- maybe the other one is like this, right? And then you have that shorter strand that's like this. And so you can't even see it. It's not in this well-defined structure. This is the way it normally is. And they have the other short strand that's like that. So you would just see this kind of big mess of a combination of DNA and proteins, and this is what people essentially refer to as chromatin. So the words can be very ambiguous and very confusing, but the general usage is when you're talking about the well-defined one chain of DNA in this kind of well-defined structure, that is a chromosome. Chromatin can either refer to kind of the structure of the chromosome, the combination of the DNA and the proteins that give the structure, or it can refer to this whole mess of multiple chromosomes of which you have all of this DNA from multiple chromosomes and all the proteins all jumbled together. So I just want to make that clear. Now, then the next word is, well, what is this chromatid thing? What is this chromatid thing? Actually, just in case I didn't, I don't remember if I labeled these. These proteins that give structure to the chromatin or that make up the chromatin or that give structure to the chromosome, they're called histones. And there are multiple types that give structure at different levels, and we'll do that in more detail. So what's a chromatid? When DNA replicates-- so let's say that was my DNA before, right? When it's just in its normal state, I have one version from my dad, one version from my mom. Now, let's say it replicates. So my version from my dad, at first it's like this. It's a big strand of DNA. It creates another version of itself that is identical, if the machinery worked properly, and so that identical piece will look like this. And they actually are initially attached to each other. They're attached to each other at a point called the centromere. Now, even though I have two strands here, they're now attached. When I have these two strands that contain the exact-- so I have this strand right here, and then I have-- well, let me actually draw it a different way. I could draw it multiple different ways. I could say this is one strand here and then I have another strand here. Now, I have two copies. They're coding for the exact same DNA. They're identical. I still call this a chromosome. This whole thing is still called a chromosome, but now each individual copy is called a chromatid. So that's one chromatid and this is another chromatid. Sometimes they'll call them sister chromatids. Maybe they should call them twin chromatids because they have the same genetic information. So this chromosome has two chromatids. Now, before the replication occurred or the DNA duplicated itself, you could say that this chromosome right here, this chromosome like a father, has one chromatid. You could call it a chromatid, although that tends to not be the convention. People start talking about chromatids once you have two of them in a chromosome. And we'll learn in mitosis and meiosis, these two chromatids separate, and once they separate, that same strand of DNA that you once called a chromatid, you now call them individually chromosomes. So that's one of them, and then you have another one that maybe gets separated in this direction. Let me circle that one with the green. So this one might move away like that, and the one that I circled in the orange might move away like this. Now, once they separate and they're no longer connected by the centromere, now what we originally called as one chromosome with two chromatids, you will now refer to as two separate chromosomes. Or you could say now you have two separate chromosomes, each made up of one chromatid. So hopefully, that clears up a little bit some of this jargon around DNA. I always found it quite confusing. But it'll be a useful tool when we start going into mitosis and meiosis, and I start saying, oh, the chromosomes become chromatids. And you'll say, like, wait, how did one chromosome become two chromosomes? And how did a chromatid become a chromosome? And it all just revolves around the vocabulary. I would have picked different vocabulary than calling this a chromosome and calling each of these individually chromosomes, but that's the way we have decided to name them. Actually, just in case you're curious, you're probably thinking, where does this word chromo come? I don't know if you know old Kodak film was called chromo color. And chromo essentially relates to color. I think it comes from the Greek word actually for color. It got that word because when people first started looking in the nucleus of a cell, they would apply dye, and these things that we call chromosomes would take up the dye so that we could see it well with a light microscope. And some comes from soma for body, so you could kind of view it as colored body, so that's why they call it a chromsome. So chromatin also will take up-- well, I won't go into all of that as well. But hopefully, that clears a little bit this whole chromatid, chromosome, chromatin debate, and we're well equipped now to study mitosis and meiosis.

Sister chromatids

Chromatids may be sister or non-sister chromatids. A sister chromatid is either one of the two chromatids of the same chromosome joined together by a common centromere. A pair of sister chromatids is called a dyad. Once sister chromatids have separated (during the anaphase of mitosis or the anaphase II of meiosis during sexual reproduction), they are again called chromosomes, each having the same genetic mass as one of the individual chromatids that made up its parent. The DNA sequence of two sister chromatids is completely identical (apart from very rare DNA copying errors).

Sister chromatid exchange (SCE) is the exchange of genetic information between two sister chromatids. SCEs can occur during mitosis or meiosis. SCEs appear to primarily reflect DNA recombinational repair processes responding to DNA damage (see articles Sister chromatids and Sister chromatid exchange).

Non-sister chromatids, on the other hand, refers to either of the two chromatids of paired homologous chromosomes, that is, the pairing of a paternal chromosome and a maternal chromosome. In chromosomal crossovers, non-sister (homologous) chromatids form chiasmata to exchange genetic material during the prophase I of meiosis (See Homologous chromosome pair).

See also

References

- ^ "What is a Chromatid?". About.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "Definition of CHROMATID". www.Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 18 July 2017.