The Chinese telegraph code, Chinese telegraphic code, or Chinese commercial code (simplified Chinese: 中文电码; traditional Chinese: 中文電碼; pinyin: Zhōngwén diànmǎ or simplified Chinese: 中文电报码; traditional Chinese: 中文電報碼; pinyin: Zhōngwén diànbàomǎ)[1] is a four-digit decimal code (character encoding) for electrically telegraphing messages written with Chinese characters.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:14 1592 30210 51021 1512 668

-

A Chinese Typewriter in Silicon Valley

-

Morse Telegraph Club

-

The $11 Frog Sounds Chinese Transceiver Radio.

-

Pixie QRP - Chinese $7.00 CW Transceiver Kit (40m) 業餘無線電QRP

-

The BITX40 - Budget Friendly Hackable Ham Radio Transceiver

Transcription

>> up to recently at Google Research recently joined Google Android. As a native Chinese, I was very fascinated by Tom's work on Chinese ethnic group classification. It's actually interesting from a computer science point of view today that, how would you classify people into--who had been living, you know, who have had patch of land for thousand, thousand of years and how do you divide them into different ethnic groups? What features would you use? Is it--is the language that they speak? Is it the proximity in geography or is it the clothes they wear or how they marry? What features do we use to classify them to different categories? And Tom did the most thorough study of this, that how--officially was classified in the 1950s with the pretty important political ramifications in terms of representation even though most of the representations in province of China was talking but still, it was important for all groups to be represented. And he traced and analyzed how that project went and it was fascinating. But today, he's going to talk about another topic that is just as fascinating which truly is interesting to me because as a research scientist I've devoted a big portion to my career and study how to enter information into computers. And Tom's study shows that much of this work we do today on mobile phones, on touch screens are actually foreshadowed by what Chinese engineers and inventors have done in the past many decades. So, I'm very pleased to be able to invite him to give a talk on this topic today. So, please welcome, Tom Mullaney. >> MULLANEY: Thank you very much. Can you all hear me okay? Excellent. So, it's a great pleasure to be here and an honor and I want to thank Xu Man Jai for inviting me to speak with you today. The talk of the paper has changed many, many times, many iterations. So, we're going to keep the main title of the Chinese typewriter in Silicon Valley but the subtitle has changed a little bit from the abstract to how Chinese typists invented predictive text during the height of Maoism. To give you a little bit of context, the broader set of questions that I'm working on right now in a book, I guess tentatively titled, The Chinese Typewriter, a Global History, is a broader story of 19th and 20th century China which pretty closely connected to the history of European--Euro-American Imperialism is the question of how to render compatible--how to render the Chinese language compatible with the set of information technology such as the telegraph, the typewriter and later forms, which almost in their DNA have been so closely connected to alphabets or more generally speaking, to languages with a very limited set of modules, be they alphabets or syllabaries. And so, there was, during the 19th century and 20th century and even today, this very fundamental question that I post up here, is Chinese script, not the language as a whole, but is script, the Chinese script, Chinese characters, are they compatible with modernity or must they be jettisoned so that China can modernize. And this was a major question in the 19th and 20th Centuries with many people saying no, we have to get rid of characters, use English, even Esperanto in order to modernize. And many even more who saw--who used the imagery of the Chinese typewriter in particular, as kind of proof of this. I say proof in--I italicized that with my voice so as to say that the proof came in a sort of concocted imagined ideas of what a Chinese typewriter must theoretically look like. That would be an immense machine with thousands of keys upon which it takes even five people to type and so forth. And so, you see, some of the earliest and most derogatory and racist perceptions of this from turn of the century that top one is from an article in 1900 all the way through the kind of dregs of B movie culture with a Tom Selleck movie, the Chinese typewriter into the famous dance coined by MC Hammer in You Can't Touch This, known as the Chinese typewriter, that dance was called, because it was meant to mimic what a typist must look like as they move across a massive keyboard into the Simpsons and so forth. So, that is to say that within the story of--the question can--is Chinese--are Chinese characters compatible with modernity? The Chinese typewriter in particular became a kind of icon for those who said no, it's not. And it's a surprisingly durable icon. And what I'm here to talk about today is that parallel to the story, there's a far richer, more significant and interesting story of those who did not give up on this idea, that Chinese characters could be compatible--or rendered compatible with technologies designed without Chinese in mind. And I'm charting in my own work the kind of larger history about this involving Chinese telegraphy, typewriting, Braille, and indexing systems and so forth. But what I'm going to talk with you about today, if I had to kind of make this relevant for an audience that is obviously very interested in deep history, but is also setting out to build things and make things is that when I see the Chinese typewriter, I don't see this. I see a machine whose history is an incredible repository of designed inspiration and some of the most eccentric and brilliant innovation, most of which never saw the light of the day, never materialized into forms, but some of the most brilliant and penetrating analysis and innovation of human-machine interaction of input of data structuring and many other dimensions. And so, in particular, what I want to talk about today is a kind of episode that takes place in the 1950s in China. Now, this is going to be the sort of context and I will be explaining this in a bit. This is a few snap shots of different Chinese typewriters in the 20th century. The episode comes from November of 1956 in the pages of the most--the most widely circulated Chinese newspaper, the People's Daily which featured an article in that fall--one of the fall issues of a typist in the city of Luoyang in China that had performed this unparalleled feat and was reported to have using a Chinese typewriter whose operation I'll explain in a second, using a Chinese typewriter had typed at speeds verging on 80 characters per minute. Now, I invite you not to immediately compare that to QWERTY inputs or things like that, because there, I'm going to try to explain that they're largely irrelevant comparisons but the important comparison is how fast had a typewriter--a Chinese typewriter been at that point. Roughly speaking, if you look at a lot of the archival documents, teaching manuals and so forth in the '20s, '30s, '40s, '50s and on, the average typing speed at this moment was about 20 to 30 characters per minute. So, this thing--this event, this person doing this, if it was real, represented a three-fold increase in speed of input, if you can think of it that way, without any substantial changes to the kind of mechanism of the machine. This was not a new typewriter. This was some sort of change that had taken place to the existing machine. Now, to give you a sense of how the machine works, how these various models up here work, you'll notice that there are--there's a tray bed, if you see right here in the [INDISTINCT] model here. There's a tray bed on the 1960s Double Pigeon model, of 35 characters by 70 characters. These are free-floating metal slugs. If you were to pick up this tray and turn it over, they would all fall out. There is a tray selector that can operate along an XY axis and actually can XY--and then the tray bed itself which can move left and right along one axis. And so, you kind of move both, bring the selector in positions, pushed down on the lever and the--something pokes up the slug from the bottom, it is grabbed, inked, it strikes the surface of the platen and then it's returned into the same location. That's the basic functioning of these machines. Now then--so, if you can imagine, this is about--this is 2450 characters. So, the most important dimension of this is taxonomy, is the organization and disposition of these characters. Now, the way that in the 1920s and '30s and '40s characters on the--on the--on the machine had been organized will be very familiar to any--anyone in the room who reads or speaks Chinese, but for those of you who don't--excuse me, it was the--a system known as the radical-stroke system. And basically, this system which dates back to the Ming Dynasty, popularized in the Ching Dynasty, that is into, roughly around the 16th to 17th or 18th Centuries, we're talking about, is a system by which the tens of thousands of characters in the Chinese language are subdivided into a set of 214 classes or categories based on the primary component out of which the character is built. So for example, one category of these 214 is the person radical category, the shape here. And here are some examples of characters that fit within it, that are built out of it. The--another radical class is the water radical class here, these three strokes and you can see two characters that would fit into that. And then within each class, the characters are organized according to the number of strokes it takes to produce them. So the character Ta, meaning he would come before the character To because it takes more strokes of the pen or the brush to write the character To. This is the way that dictionaries have been organized and the way the typewriter had been organized. What the article in 1956 suggested was that this typist in the city of Luoyang had departed, had kind of taken a radical departure if you will from the system and reorganize the tray bed according to a natural language arrangement. And so if we give--if we take a sample, a very small sample of the 2,500 or so characters--those of you who don't read Chinese, follow with me now. The yellow--the highlighted yellow character is the character Tong. And the important thing about this is that unlike the previous organization which--in which that character would have been put next to characters that has nothing to do with. In this reorganization of the tray bed in 1950s, all of the adjacent--or many of the adjacent characters in the Morse neighborhood, the eight cells around it were--the disposition of those was such that they could be combined with the character Tong in order to produce a real word. Most words in Chinese are actually made of two characters not one. And so for example, this--the yellow character and--can be combined with what's below it, [SPEAKING IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE] meaning, at the same time. To the right, [SPEAKING IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE] in the same period. And then invertedly with the character above it, [SPEAKING IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE] meaning, shared. And then if you can do this with each of the characters on this, every character is both a center and a periphery can be in combined or combinable with everything around it. And, you know, we have to--when we look at an article like this from the People's Daily, which--we have to be very careful. We have to be very careful as to the story and not to believe what we read and kind of follow up. There had been many stories of model workers in the--in the--in the height of Maoism. Model laborers who out produce their quota. Model farmers who out produce their grain quota. And here we have a model typist who had out produced their typing quota, their character quota. So we have to be very careful here. But interestingly, is having spent quite a long time checking up on this, we see that this actually happened and was--I'm going to suggest here, one of the earliest implementations of a system of kind of techno-linguistic system that we now think of as predictive text or natural language arrangement or however we want to--we want to describe it. So more broadly I think before I get into the nitty-gritty of this, I think it's pretty self-evident but let me spell it out that if this is true, then what this alerts us to is the need to look very--much more seriously at a techno-linguistic innovation in three contexts where we don't often go looking for it, China, the Chinese language and in this case mechanical pre-computer system. At the very least, predictive text is not associated with Chinese Language, not associated with innovations in China and it's certainly a very rarely or ever associated with things in the pre-computer information age. So if we--if we--we have to begin by asking the question--this will be relevant here in a second. The primary innovation that I'm talking about here is obviously not a--not the design of a new machine but a new interface. This is a new interface between a Chinese typist and the machine. And so we have to ask the question, was there a context for this typist in Luoyang to kind of pick up and move around the modules on this interface? Was this a total radical--a totally radical act, a very unprecedented act or was there a context for this? And there was a context for this. And the simple--the simple framework for this is that unlike the story of the typewriter and specifically the semiotic interface of a typewriter in every other part of the world. Be it--let's refer to languages more particularly, be it English, French, Italian, Russian, Hebrew, Thai, Cambodian, Arabic and so forth, in the story of which the semiotic interface of each of these typewriters at some point stabilized into QWERTY, AZERTY, and--QWERTZ and so forth. That the story of the machine interface of the Chinese typewriter never stabilized, was never meant to stabilize and was understood as something that would constantly need to be adjusted or changed by the operator through a constant process of optimization. Why is that? The reason for this is--comes in the fact that the basic--let me put this up here, that the basic structure of the Chinese typewriter was based on the system called common usage. So there are many more than 2,400, 500--2,450 characters in Chinese, there are tens of thousands. The idea of the common usage Chinese typewriter, and that's what we're talking about, is to select the most frequently used characters and to put them on the tray bed. And then the rest of them would either be in a box about 5,000 characters of less commonly used characters and then anything else beyond that would have to be written by hand, okay? Now, the sort of--the issue for us here is that no matter how perfectly you chose these 2,450 characters, no one set would be perfect for every given context. In a police office versus a bank, the common usage character would be different from one to the other. And so therefore a typist in a police office--police office would have to take an uncommon character and put it on the tray bed, and the same thing for a typist in a bank or a government office and so forth. The other, there's a diachronic or a temporal part of this optimization story which is that from moment to moment, common usage characters fell out of existence, uncommon characters became common and some very--some prime examples of that pertain to the administrative geography of China. So for example in the--in the teens and early 20s, there was a province known as Fung--I'm sorry, as Jiuli Province, so--but--so the characters Jiu and Li both appear on the machine in the teens. After roughly the mid 20s, the province of Jiuli was abolished as an administrative region and was divided into a set of new provinces. Now, what happens to the tray bed? The character Jiu is very, very common in many, many, many other Chinese words and so it was kept. The character Li is very uncommon on its own and so it was judicent, the same thing happened with the province known as Fung Tien, which no longer exists. And after this transition, you can compare the tray beds and see that the character Tien which means sky, very, very common is kept and the character which means Fung which means to present something to a superior was a very, very, uncommon character in--and so it was judicent. So this is all to say that there was a kind of built-in--already a built-in kind of churning optimization process in which these operators in 1956 would have been operating. It's very interesting that--so actually, let me--let me tell you a little bit more about the structure of the tray bed here. Here are three different tray beds from three different periods just to get this impression in your mind. The red region are the most commonly used characters. All of these are commonly used but these are the most common used characters and then the dark blue or the kind of purplish regions are the secondarily common usage. And I'll talk about that kind of light blue in a second. So there was even a structuring of frequency within the tray bed that will become relevant in just a moment. And what's interesting about this is it's not just--the optimization of the machine was not simply at the level of the tray bed and the disposition of characters on it, it was also a question of how a Chinese typist would undergo training and how they train their body. And to put this in a comparative context again, because it helps illustrate the point, in Roman alphabet or Cyrillic, or Hebrew, or Arabic or so forth typing, the ideal state of being when you are typing is known as blind typing. If you are sitting there staring at the keyboard, you better go and practice a bit more. You know, the idea is that you can look at the manuscript or the text and then have a kind of non-visual relationship with the interface and just go. This way of interacting with the machine makes a lot of sense in alphabetic and syllabaristic languages and makes no sense and was never endorsed in the case of Chinese typewriting. For the Chinese typist and I put up some various typing manuals from different points in 20th century Chinese history actually emphasized the need for the typist to refine to ever greater and greater ability their vision, and their memory, and their peripheral vision. And I'll give one example. The idea--one of--one of the most important parts of being a good typist was to always be anticipating both cognitively and somatically the next character, the next character, the next character. So, if you were to go to one character that is all the way over to the right of A tray bed, I know that my laser point doesn't work very well. Let's say you need a character over here, and then you know--you're looking at the manuscript, you see the next character and you realize that it's over here, you need to start kind of orienting your body in such a way TO getting ready to move it back in that direction. You know. And if you don't do that, you'll still be able to type but you'll type very slowly. So that is to say that even in the training of the Chinese typist because of the sort of almost built-in affordances and limitations, constraints and abilities of the machine that we see in analog to this in which--in the way that a typist would train in China as opposed to many other techno-linguistic context. One other very quick example that I like very much pertains to the--what those of you who have read any [INDISTINCT] would know is materiality of signifiers and in a more concrete sense means that the typist would have to adjust the strength, the force that they use to press down on the typing lever, depending upon the number of strokes in the character, because the number of strokes in the character translated directly into the weight of the character. And so, what--some characters are one stroke like the character "e" meaning one, is just one horizontal stroke. And then there's another one for dragon long, which has many--more than 20 strokes. If you use the dragon strength force on the character one, you could puncture the paper and therefore have to start all--start all over again. And so this idea of--kind of optimization anticipation operated on many, many levels. Okay but this is--this is kind of necessary but insufficient set of conditions to get us to this more radical change, the semiotic change, this change of interface that takes place I'm arguing in the 1950s, and so how do we get to a place where in 1956 someone actually sits down and removes all of the characters from the tray bed and then rebuilds some sort of natural language arrangement of all of the characters. How do we get to the place where someone would feel mandated or authorized or inspired to do that? The question of this is really connected to the politics of the 1950s--the politics of the 1950s. And in particular, a politics that was, within 20th century China, unique to the Maoist Period, which was a centrally endorsed, proletarianization of knowledge that is kind of user-led innovation in a sense where in a vast number of different expert domains including seismology, paleontology, medicine, the State--the Central State in Beijing and the Communist Party was advocating mass participation of none elite, kind of, participants in these otherwise expert systems, and was also advocating the really--the overturning of knowledge systems. And the kind of, if you want to say--if you want to put it in the kind of a prose format to take much more seriously folk knowledge, to take much more seriously the knowledge that everyday people have. And so there does seem to be a strong correlation between this advocacy that's--and mandate in authorization that's being issued from the party states and the type of experimentation we see in the 1950s. So, its very, very difficult to locate the origins of moments like this, and in many cases finding an exact point is not all that important. But if we had to--if we had to choose the first moment in which we see a natural language arrangement of Chinese characters in an information technology environment, it takes place not in typewriting but in typesetting. In the City of KaiFeng with the work of this--a typesetter named Zhang Jiying. And Zhang Jiying worked as a typesetter both in the pre-Communist era in the 1940s and then into the early--into the Maoist Period in the '50s and he posted very respectable typesetting speeds throughout most to his career, and his character rack, the rack where all the characters were displayed for his use were also organized, largely according to the Radical Stroke System, the same one that we saw before. Around 1951-'52, inspired by this new mandate for the proletarianization of knowledge mass participation and so forth, he began to reorganize these characters, to maximize the adjacency of those characters that go together. Some of the kinds of prime examples for these come from the name of the Press he worked at, the Xin hua she. So he said, well I'm constantly setting Xin hua she so why should I reach around this character rack, why not just put them next to each other? Another example is Ge ming, Revolution. I'm constantly saying ge ming or constantly setting this type, so might as well put them together, and then my favorite is, mei di, American Imperialist. This was the time--this was the time of the Korean War in the first really Nationwide Campaign of the Maoist Period which was Aide Korea--Resist America, Aide Korea as--in connection with the Korean War. So these phrase mei di was said over and over and over again. Now what's interesting is it's very hard to say, was Zhang Jiying inspired by this--by this central new mandate of the Communist Party or were many people doing this and we just don't know about it. It's very hard to say the one thing that we do know is that the party state was not only advocating or promoting this type of proletarianization of knowledge but whenever it happened in a locale or a region, they were publicizing it and popularizing it. So Zhang Jiying was actually--became something of a little media star for a few years. He was--he was featured in the People's Daily, there was a book published about his method, he was sent on a paid tour of China, to various printing houses to tell people about his method, the Central Broadcasting Company filmed him doing his job and he was eventually admitted into the party, and so he kind of, was a--his method was celebrated. It's very quickly after that celebration of his method that we start to see the same application of natural language arrangement of the--of key--of characters on the Chinese Typewriter. And this brings us back to the 1950s in the story that began the talk. So this brings us back to again the same--the same example. Now what's interesting about this is that there are--if on a 42-key keyboard, there are 42 times 41 times 40 so forth possible arrangements on a key--on a tray bed with 2,450, there are 2, 450 times so forth and so on. There is effectively infinite number of arrangements--possible arrangements of these characters. And so, we see is that in after this--after the predictive turn in the 1950s, we see multiple people applying this to their own tray beds centering around certain basic--basically shared principles and yet each of them completely individualized and completely idiosyncratic. There are no two predictive tray beds that are--that are alike. And let me give you just a few examples of these. There's two tray beds that I'd like to talk about. One is a Chinese Typewriter used at the Paris--the Unesco Office in Paris. Another one is use in the United Nations Office in Geneva. These are two separate Chinese type--typewriters and typists working in very different contexts and I--and I'll walk you through this as well. On the left one here--and this is a 1930s just to give a comparison against the pre-predictive tray bed. In the middle here, in the Unesco Machine we see this character in yellow Mao, this is the surname of Mao Zedong. And if we look to the--below it, we--the two characters below it are Zedong, so that he could type or she could type Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong quickly and easily. Emanating off to the right of it are--is the character--are the characters Ju and Shi, Jushi, Mao Jushi which is Chairman Mao. And so kind of the Mao is again constellated in such a way that it can be kind of concatenated with a bunch of different characters that this typist needed. In the right example, in the Geneva Machine, we see the exact same idea but in essence constellated differently. We see again the character Mao in yellow, and now Mao Zedong doesn't go up--down as in this example but all off to the left. And Mao Jushi, Chairman Mao doesn't go off to the right but goes down. So in essence we see these typists converging around certain principles but each one very idiosyncratically organized. To make this a bit clearer for those, you know, for those who don't read Chinese we have the example of punctuation. Predictive text was even applied to punctuation in then actually in numerals. But anyway, in the 1930s the question mark, exclamation mark, period, comma, were put where they kind of rationally belong all together in one place and after the '50s a set of typists began to say, well that doesn't make much sense. We know that question marks always come after a question particle because that's how you express--that's one of the ways you express the interrogative in Chinese is by the addition of particles. We know that the particle--that the characters ma, ba and na those are in red there are always followed by the question marks so that's constellated around the question mark on the machine. We see in the United Nations machine by comparison the exact same idea but again a different configuration of these other particles. Now why are they differently configured? And this is the really fascinating thing that I'm sort of working with various set of data visualization specialist and others to try and think about, it could be all sorts of things left-handedness, right-handedness this is sort of mnemonic devices that one person prefers to remember the location or another. All sorts of factors could go in to why this idiosyncrasy prevails but the really--but kind of anchoring any of these idiosyncratic personalization are again these kind of cohering strategies that we often see from one example to the other. This is a basic heat map which is--basically visualizes the--is a calculation of adjacency it's the bright red or the dark red patches are those that in which the character can be combined with maybe seven--six, seven, or eight of the characters in the surrounding area the kind of--the whit, the very, very, very light white-red, the white can be combined with one and then the black here indicates that the character cannot be combined with any of the characters in the Morse neighborhood to form a real Chinese word. This is a heat map of a tray bed from the Republican period 1911 to 1949 before the type of innovation I'm taking about. So you can see that there is some almost accidental situations in which a character is flanked by other characters that it can be combined with and then there's one part here that I'm happy to talk about why there's--why there is a collection there. The important thing is that once we go to 19--after 1949 this is what the tray bed looks like it heats up, it lights up because the basic principle again is the maximization of adjacency of related characters. So to put them side by side we can kind of get a sense of what all of these incremental innovations in the interface of the machine translated into and this is how we explain an acceleration of the speed of typing that could be that high as indicated in the People's Daily. Not just this leap, it's not just this leap that is so interesting it's also again the variety between different interfaces. These are--both the UNESCO and the UN machine both of them predictively, a natural language arrangements, and how differently each of them behaves. They have clusters in different places they--the kind of architecture of the arrangement is very, very different and again in terms of interpreting why that's a very challenging active--of working backwards from the arrangement by the 19--late 1980s and into the 1990s we begin to see Chinese typewriting companies and Chinese typewriting instruction manuals, the appendix of which used to carry grids like tables that showed you where all of the characters on the tray bed are, you know, it's a very important thing for a manual to teach you. By the 1980s and 1990s we begin to see tables like this that are empty because they're basically saying to the user you decide, you decide where to put the characters. Now there are some suggestions these characters here, well it's hard to point too, the characters along the side are saying you should probably--you could probably put characters about Communism here, you could probably put characters about higher-education here, about war here, about science here, about and they're--but they're just suggestions ultimately it is left to the typist to decide where all of these arrangements are taking place. So in essence what this speaks to me is that machine--the manufacturers of these machines were in effect catching up with something that was a user lead innovation. So to close I just want to ask a few sort of set of open questions, the first set of questions is kind of what about the computer? You'll notice that electrical automation, computing, word processing is noticeably absent from this talk it's entirely about mechanical typewriting environment and if you go into the discussions of various innovation by BAIDU, or by SOGO, or by various input methods that use predictive or algorithmic probabilistic determinations for input. The assumption, the prevailing assumption is that this was kind of the--thanks to the computer which like the Data ex Machina comes in and saves Chinese from itself in essence, and what you see actually when you look into the history of early Chinese computing in the '60s and '70s is by in large the virtualization or digitization of principles and applications that had been developed in the mechanical Chinese typewriting environment. That is to say that at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and various others working in the late '60s and '70s, they are very aware of what's going on in the mechanical Chinese typewriting environment and they're trying to basically enhance or build upon that and it's not a question of this innovation coming in exclusively from the outside and changing the game as it were. So the larger question I guess is that--and I give this example here in BAIDU, excuse me, the BAIDU example all input systems not just search engines but all input systems for Chinese are all make use of predictive text, all of them now, and so there is this important question of where does this come from in the history of Chinese computing and Chinese internet. And quite obviously I'm arguing that there's not an exclusive genealogy that dates back into the history I'm talking about but one that certainly combines the history of Chinese typewriting and the history of computing more broadly. So if this is true, the question is a sort of bigger question, is how did we miss the typing rebellion? If there was this--no Chinese historians in the group so--okay, there's this massive civil war in China could the Typing Rebellion. Anyway, there is a question of that if this innovation is taking place in the 20th century then how do we keep missing it? How do we--why do we, in large part, continue to ignore the history of information technology in China before maybe five, ten years ago and imagine it as being--in essence more of proof of the anti-modernity of Chinese than anything we would ever look into to be inspired in our own innovation and what I would like to suggest is that, not only for my own purposes, but also maybe even for designers among you who are looking for massive repository of experimentation and innovation, which may have not seen the light of day but may itself provide inspiration and blueprints for things moving ahead. I'd like to suggest that the Chinese typewriter as a problem, historically has operated in very similar type of inspiration as the original billboard ad back in the day that was designed to kind of challenge and inspire the most innovative, eccentric kind of thinkers in the world and the Chinese typewriter in it's own way, throughout the course of the 20th century, became a magnet for not only innovators in China but from all across the world and same thing with Chinese computing and now into later technologies. And so it is actually an immense repository of inspiration and principles that I think we could all profit from looking more deeply into. Thank you very much. I'm happy to take questions. Why don't we start on the right and then go to the middle. >> So we speak a little bit about how these typewriters actually work in terms like how big they are, how do they get set-up because first thing's one of the things about this is it makes your typewriter a very personal device or you have to arrange it to your--to your additive [INDISTINCT] sit down at any keyword and you expect [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right. >> And that seems like a very different shift [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right, absolutely. Could everyone hear the question? Okay. So the machine was roughly--let's--I'll just use my hands, is roughly about this wide--the tray bed itself is about this wide and this deep, okay, and then machine itself kind of--may juts out from the back maybe about this far and it comes off--from top to bottom it would be about yay tall very, very heavy. So the--the dimensions of it are pretty comparable with many desktop systems we see but the weight of it is significantly higher but what you're talking about here, this kind of built in--this built in, almost personal relationship between the operator and the typist--and the machine is absolutely true. So even before what I'm describing as a predictive--kind of a predictive turn in the interface, you would have to personalize your machine. Not only in terms of the time period and whether or not you're work in a bank or a law firm as I suggested but things like maybe your co-worker or your boss has a surname whose character--the character if the person surname is within it of itself, very infrequent. It doesn't show up in newspapers very much but for you, it shows up everyday, every page. And so, you would have to make sure that your machine has that name. And so, if we imagine a scenario in which, you know, someone was sick that day and couldn't come in and someone else had to sit down at the machine. There would be a--before 1949, there would be kind of basic road map. The person would know that this is organized according to radical stroke but beyond that basic road map they might not know where to go. They might not know how the other person personalized it. So, it is a very different interface just as a build--from the GETCO than type writing in practically any other language that we--that we--that we see. And then after 1949 this becomes even more so. You would not be able to use really effectively a typewriter that someone else had rearranged according to their own natural language arrangements. The tray bed is almost an embodiment of their consciousness. If you think about it, it's how I remember where everything is, how my body works, how I prefer this to be. And then you come and try to use it. It's like trying to figure out someone else's file folder structure on their laptop. It's very, very personal. The gentleman in the--in the sweater and then to the gentleman with the glasses, yes? >> So you mainly talk about how people with their group--language, natural language [INDISTINCT] is there any evidence you're reading [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: I know, yeah. >> That, you know, [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: That's a great question. Yes? >> Do we have to repeat the question for the remote the audience? >> MULLANEY: Oh, for the remote audience. Oh, I'm sorry. The question is--the question is, so the talk mainly focused on how innocent people with their understanding of and their use of natural language--their own use of the language reorganized the interface of the machine. Is there any evidence to suggest that the kind of reorganization of the interface machines cycled back and really transformed language? The quick answer is, I suspect so. The longer answer is I suspect so but it is going to take massive corpus analysis to really decide whether or not that that's happening. We'd have to--we'd have to do stuff that really has never been done with the analysis of Chinese language material high throop. I mean it really depends upon Chinese OCR becoming better because we would need top do immense corpus analysis to see whether or not there are changes overtime. The one thing that maybe countervails against it--against the possibility, so that is to say that I suspected it's true but one thing that maybe suggested is not--is that the Chinese Typewriter was mainly a re-inscription device, a re-productive advice. It was--you would start out with a manuscript or something and you would copy it, you would produce a type--a type script version of it. What you don't see in the context of Chinese Typewriting as opposed to practically every other typewriting context, is then idea of the author sitting down at a machine and producing a manuscript, like there's no such thing as Lin--the writer Lin Yu Tang in China sitting down in his Chinese typewriter the way that Allen Ginsberg might sit down. And this comes back to the common usage system that not all of the characters are there. And it is the job of the poet and the job of the writer to in fact to delve into the infrequent and the beautiful. And so, maybe not but I think that that's one--that's one area that I'm trying to team up with distant reading and corpus linguistic specialist to see if it's possible to ask that, to ask that question about linguistic change. The gentleman in the glasses and then the gentleman in the black leather. >> So, there was also this [INDISTINCT] the simplified Chinese. Do you think to wish to simplify typing and wish to simplify writing would be correlated--basically correlate the [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Sure. The question is, you know, that the relationship between simplification campaigns and then this kind of taxonomic reform of the--of the tray bed are there any relationships? Because they are happening at the same time. There are happening in the early 1950's under the--in during Maoism they take--they take place in the '50s. There was an earlier aborted effort to simplify characters under the Republican regime but the places where they seem to be related is that the typewriter became--and the tray bed in particular became a highly politicized space or domain if we think about because for example, during the simplification campaigns, there were no--there were notifications sent to typewriting manufacturers saying that you need to replace these traditional characters with simplified characters now. Which from their perspective is a monetary--you know, is a financial burden--there's a financial burden on people at the local level to--that's theoretically half to replace the character with another one that has been identified as the simplified version. And, so people were reticent to that because it just--it just kind of cost money and was a--was a--was pain. And so, it became one of the places that the--that the--that the communist government was very eager along with printing presses, a very eager to promote simplification because these were obviously the places that produced texts. So, you want to go to the--if you can change the characters on a typewriter and change a character on a type--a printing press then you therefore transform every piece of every page that gets produced thereafter. So, in terms of them interacting or relating to each other causally I don't see that all that much but they are connected historically. Yes, sir? And then the gentleman. >> So, underlying the couple of assumption that [INDISTINCT] I grew up in this country and there wasn't a lot reading the newspaper. So, the language became very I would say [INDISTINCT] so, I wonder if there's any study on how much it affected the language. Because it proves to make it more [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right. The question-if I can--if I can synthesize it, let me know if I get it right. Is--I'd say it is the question, is there--is there a relationship between the kind of templetization--I like that word, of language in Mao--in Maoist China which relates to kind of--the kind of Newspeak phenomenon that happened in many communist context and this--that because the language was in essence more predictable, that it was more amenable to a predictive text arrangement. And the answer is--I mean I think yes. You know, in a longer paper, in a longer project that's actually an entire part of the argument is that the emergence of a un--of a--of a--of a political rhetoric, of unprecedented standardization during Mao--the Maoist period of unprecedented kind of routedness was itself largely facilitated the creation of a tray bed in which it would be very useful to create a natural language arrangement because, you know, that you're going to be saying American imperialist--the American imperialist over and over again. What's facilitating about it I think is that, normally the idea of Newspeak this kind of 1984 image of the communist rhetoric is typically understood as an inhibition as an inhibiting factor to innovation. It inhibits thought because you can--it kind of, you know, that's a--it's double plus good kind of idea of language. And it seems that perhaps there is--there's a lot of credence to that argument. But in this case, the--we see the exact opposite. That for the--for at least in this context Newspeak is inspiring or part of a history of radical techno-linguistic innovation in which there is a--there is a kind of encouraging or inspiring momentum for the typist to make the tray bed as idiosyncratic and personally optimized as possible. So, that they can more and more efficiently produce texts that are more and more route if you see what I mean. So, there's a--there's--do you see what I mean? There's actually--there's actually a relationship between innovation and Newspeak that we--that we rarely see another context but that is highly relevant--highly relevant here I think. Yes? In the back and then--in a black sweatshirt. >> Okay. You mentioned... >> MULLANEY: Oh, I'm sorry. >> You mentioned various factors [INDISTINCT] how about spoken dialect, is that [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: The question pertains to spoken dialect and if I can--if I can broaden it out because it is a really interesting questions about--I mean really the question of dialect and Chinese language information technology as a whole is a very, very political question throughout really the 20th century. For the most part, there has been a kind of antagonistic relationship between Chinese information technology and dialect. In the sense that people had been political leaders manufactures and others had been very resistant to the idea of developing for example, Cantonese input or Shanghainese input or Taiwanese input or to--even before that--before we think of input and whatnot. The question of whether or not different dialects in Chinese should be outfitted with their own written languages and whether or not people should be able to publish for example a book in Cantonese where the characters are actually--there are many Cantonese characters which do not exist in Mandarin Chinese should people be allowed to publish in that way which is also a kind of information technology question and the answer has consistently been, no because if we--if we pair up the massive diversity of dialect diversity in China with written form we will in some sense institutionalize these cleavages and that could actually damage the territorial integrity of the country. That's why most regimes in the 20th century in China had been very, very--and another elite, political elites have been very focused on the promotion of a single standard. And so for example with pinion with Chinese pinion inputs that is actually a--not only an information technology tool but a pedagogical tool that people know that if they're going to use a computer in China they have to use pinion input and pinion input is route is connected directly to the Chinese standard. And so the very active learning how to use a computer is in some way shaper form becoming oriented towards the standard. And so they've been very resistant to develop alternate techniques for that. And let me just jump to you I'm very sorry. >> Yes. I'm trying to kind of like you to get the kind of answer I really [INDISTINCT] did you try to--kind of figure out how they actually basically try to reverse the communication process applicable to this and how the actual typist make this happen? [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right. >> But how did they do it with like the numbers they're very equipped [INDISTINCT] very large numbers. >> MULLANEY: Right. >> And how do they arrive at that, I mean [INDISTINCT] I mean whenever we [INDISTINCT] too far things, we just Google near each other [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Yeah. So the question in this--the basic question is how did these re-engineers of their machine do it, how did they go about the process of producing these natural language arrangements, tray beds that's actually why or how I came to be here today was I gave a talk at Stanford which is my home institution and it was within STS and STS contacts was attended very luckily for me by Scott Clemer from HCI at Stanford who then invited me to give a talk there and I was talking with Scott and I said I need to, I need to talk to someone who works on optimization because I need to know how someone right now would think about the optimization of such a hyper-complex system not because I want to build a Chinese typewriter but because I want to hear someone talk about the process of optimization so that I can--so that it can excite my imagination and excite my sort of heuristic complex so that I can go back and have more intelligent--search more intelligently for exactly the answer that you're talking about. It is entirely a question there's two pathways to answering the question, I don't have an answer yet that's going to be--that's the kind of reason that I actually first emailed I'm sorry--to complete the story, then Scott said you need to talk to Xu Man Jai and then he put us in contact we had a really wonderful conversation and then that manifested itself in today but I have to admit with the tools of my disposal I'm at a loss because there I can try to reverse engineer from the tray beds that I have and that's where I really need to pair up with someone who thinks about those problems everyday and then the other thing that I can line up is ethnographic or oral-historical interviews with typists. But even that is a very challenging thing, tell me back in 1970 how you decided to move character one to space x and character--that's--you know that's embodied memory. They--that's not something that they're going to written down somewhere so even that is a incredibly challenging process but that's I think an incredible pay off not just for me as an historian but for designers who are looking for inspiration in my opinion. The gentleman on sorry--well actually I'm sorry maybe if I can keep the order and then resume in. Yes. >> [INDISTINCT] it seemed like, you mentioned [INDISTINCT] and character may have to be [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right. >> To be here you have to lose every character. >> MULLANEY: Yes. >> You have to actually hit the [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: Right. >> You have to put that actually [INDISTINCT] like [INDISTINCT] >> MULLANEY: No. No. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So the question pertains to before 1949, before the natural language rearrangements here. Even--how did the process of optimization of tray beds in the Republican period take place and the process that you just describe is exactly what would've been required there is no, I've seen no tray beds where some characters just strangely out of place and--but everything is always in place so if you think about it the closest analogue we have is the kind of that gain with the missing plastic with a plastic pieces with one piece missing and you've got to move it around, you move one thing everything must move, everything must move to fill in the space and so yes so even so that's an important dimension here is that even before the '50s there is some--there is a--there are dimensions or characteristics that are built into the tray bed itself and into this particular techno-linguistic apparatus that provided a context with a more radical transformation we see in the '50s. But every tray bed I've ever seen exhibits no laziness in terms of some weird character out in the middle of nowhere so yeah. Yes? >> Tom, as historian with a many to sustain such a political context to major changes to the institution but much of the results could be looked at or design purely problem of language or efficiency point of view just--or even in purpose we can optimize the arrangements so you had pasted on [INDISTINCT] so I wonder with your [INDISTINCT] is to wonder how important these political, social background. >> MULLANEY: Right. That's--I feel like--I feel like I owe you something because I--you gave me a chance to kind of mention one slide that I skipped which was very important which was the fact that--let's see if I can find it very quickly--that even in the Republican period there was one small part, remember the--remember the--remember in the heat map there's a one little bright red part there was a cluster there was one tiny, tiny region of the tray bed roughly two cells wide by maybe 10 cells tall so out of 2500 roughly, it's a very small a region which were arranged according to natural language arrangements and these were province names. So the example up here has a let's look at the character Jhang that's highlighted in yellow which means river Jhang can be combined with diagonally Sou create a province name Jhang Sou. It can be combined with the character to it's left Ju for Ju Jhang which is another province and then it can be combined through this kind of neat kind of knight like a chess kind of thing of Halong Jhang from the bottom to the top to the right. This was the one, there's few important things about this. One is that we know both here and in very esoteric discussions by some language reformers that people were thinking about this in the '30s, they were thinking about this. They were kind of--it was in the general swirl of possibility as a known thing and at the same time we also know that in the '20s and the '30s was a time of hyper innovative, hyper iconoclastic language reform. This was the time when people were saying let's get rid of all the characters and replace it with French. Let's simplify all the characters let's replace it with a symbolic notation system. Very, very crazy sort of ideas and yet even with this context the step towards the kind of radical departure towards this new arrangement was never, never tried to my knowledge and I've seen a lot of these machines now more than I cared to admit and so there seems to be--it seems to be that if this is purely a question of efficiency and optimization that we would have seen something far earlier because people would've known it [INDISTINCT] that it was just something was keeping the dams, the water behind the dam and that it really took the--it really took the '50s and it really took Maoism and it really took this idea of the kind of mass overturning knowledge systems to lay dynamite to that dam and just say okay everybody, do whatever you want to the tray bed, do whatever you want however you see fit and then from that moment on it takes place because in the people's daily it shows up in three different places, it shows up in dozens of other places and not everyone does it but suddenly it starts to spread out until by but again that slide from the 1980s shows that even typewriter manufacturers were like okay you guys are better at this than we are, you have better ways of optimizing your machines than we could ever come up with so the semiotic interface is yours basically. So I do think that there is, I thought about that for a long time and ultimately I came to the conclusion that the last piece of the puzzle on this is counter intuitively Maoism. >> Unfortunately we reached the end of the--this--[INDISTINCT] talk. Let's thank again for Tom. Thank you. For those of you who want to--thank you very much.

Encoding and decoding

A codebook is provided for encoding and decoding the Chinese telegraph code. It shows one-to-one correspondence between Chinese characters and four-digit numbers from 0000 to 9999. Chinese characters are arranged and numbered in dictionary order according to their radicals and strokes. Each page of the book shows 100 pairs of a Chinese character and a number in a 10×10 table. The most significant two digits of a code matches the page number, the next digit matches the row number, and the least significant digit matches the column number, with 1 being the column on the far right. For example, the code 0022 for the character 中 (zhōng), meaning “center,” is given in page 00, row 2, column 2 of the codebook, and the code 2429 for the character 文 (wén), meaning “script,” is given in page 24, row 2, column 9. The PRC’s Standard Telegraph Codebook (Ministry of Post and Telecommunications 2002) provides codes for approximately 7,000 Chinese characters.

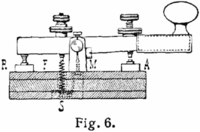

Senders convert their messages written with Chinese characters to a sequence of digits according to the codebook. For instance, the phrase 中文信息 (Zhōngwén xìnxī), meaning “information in Chinese,” is rendered into the code as 0022 2429 0207 1873. It is transmitted using Morse code. Receivers decode the Morse code to get a sequence of digits, chop it into an array of quadruplets, and then decode them one by one referring to the book. Due to the fact that non-digit characters were not used, the Morse codes for digits could be simplified, for example one's several consequent dashes could be replaced with a single dash.

The codebook also defines codes for Zhuyin alphabet, Latin alphabet, Cyrillic alphabet, and various symbols including special symbols for months, days in a month, and hours.

Senders may translate their messages into numbers by themselves, or pay a small charge to have them translated by a telegrapher.[2] Chinese expert telegraphers used to remember several thousands of codes of the most frequent use.

The Standard Telegraph Codebook gives alternative three-letter code (AAA, AAB, ...) for Chinese characters. It compresses telegram messages and cuts international fees by 25% as compared to the four-digit code.[3]

Use

Looking up a character given a number is straightforward: page, row, column. However, looking up a number given a character is more difficult, as it requires analyzing the character. The Four-Corner Method was developed in the 1920s to allow people to more easily look up characters by the shape, and remains in use today as a Chinese input method for computers.

History

0001 to 0200 (Viguier 1872). These codes are now obsolete.The first telegraph code for Chinese was brought into use soon after the Great Northern Telegraph Company (大北電報公司 / 大北电报公司 Dàběi Diànbào Gōngsī) introduced telegraphy to China in 1871. Septime Auguste Viguier, a Frenchman and customs officer in Shanghai, published a codebook (Viguier 1872), succeeding Danish astronomer Hans Carl Frederik Christian Schjellerup’s earlier work.

In consideration of the former code’s insufficiency and disorder of characters, Zheng Guanying compiled a new codebook in 1881. It remained in effect until the Ministry of Transportation and Communications printed a new book in 1929. In 1933, a supplement was added to the book.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the codebook forked into two different versions, due to revisions made in the Mainland China and Taiwan independently from each other. The Mainland version, the Standard Telegraph Codebook, adopted the simplified Chinese characters in 1983.

Application

The Chinese telegraph code can be used for a Chinese input method for computers. Ordinary computer users today hardly master it because it needs a lot of rote memorization. However, the related Four-Corner Method, which allows one to look up characters by shape, is used.

Both the Hong Kong and Macau Resident Identity Cards display the Chinese telegraph code for the holder’s Chinese name. Business forms provided by the government and corporations in Hong Kong often require filling out telegraph codes for Chinese names. The codes help to input Chinese characters into a computer. When filling up the DS-160 form for the US Visa, the Chinese telegraph codes are required if the applicant has a name in Chinese characters.

Chinese telegraph code is used extensively in law enforcement investigations worldwide that involve ethnic Chinese subjects where variant phonetic spellings of Chinese names can create confusion. Dialectical differences (Mr. Wu in Mandarin becomes Mr. Ng in Cantonese (吳先生); while Mr. Wu in Cantonese would become Mr. Hu in Mandarin (胡先生)) and differing romanization systems (Mr. Xiao in the Hanyu Pinyin system, and Mr. Hsiao in the Wade–Giles system) can create serious problems for investigators, but can be remedied by application of Chinese telegraph code. For instance, investigators following a subject in Taiwan named Hsiao Ai-Kuo might not know this is the same person known in mainland China as Xiao Aiguo and Hong Kong as Siu Oi-Kwok until codes are checked for the actual Chinese characters to determine all match as CTC: 5618/1947/0948 for 萧爱国 (simplified) / 蕭愛國 (traditional).[4]

See also

- Code point

- Four-Corner Method, a 4-digit structural encoding method designed to aid lookup of telegraph codes

- Telegraph code

- Wiktionary page of Standard Telegraph Codebook (标准电码本(修订本)), 1983

Notes

- ^ Simply diànmǎ or diànbàomǎ may refer to the “Chinese telegraph code” whereas diànmǎ is a general term for “code,” as seen in Mó'ěrsī diànmǎ (simplified Chinese: 摩尔斯电码; traditional Chinese: 摩爾斯電碼) for the “Morse code” and Bóduō diànmǎ (simplified Chinese: 博多电码; traditional Chinese: 博多電碼) for the “Baudot code.”

- ^ The Tianjin Communications Corporation (2004) in the PRC charges RMB 0.01 per character for their encoding service, compared to their domestic telegraph rate of RMB 0.13 per character.

- ^ Domestic telegrams are charged by the number of Chinese characters, not digits or Latin characters, hence this compression technique is only used for international telegrams.

- ^ For more information, refer to: A Law Enforcement Sourcebook of Asian Crime and Cultures: Tactics and Mindsets, Author Douglas D. Daye, Chapter 20

References and bibliography

- Baark, Erik. 1997. Lightning Wires: The Telegraph and China’s Technological Modernization, 1860–1890. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30011-9.

- Baark, Erik. 1999. “Wires, codes, and people: The Great Northern Telegraph Company in China.” In China and Denmark: Relations Since 1674, edited by Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard and Mads Kirkebæk, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, pp. 119–152. ISBN 87-87062-71-2.

- Immigration Department of Hong Kong. 2006. Card face design of a smart identity card. Hong Kong Special Administrative District Government. Accessed on December 22, 2006.

- Jacobsen, Kurt. 1997. “Danish watchmaker created the Chinese Morse system.” Morsum Magnificat, 51, pp. 14–19.

- Lín Jìnyì (林 進益 / 林 进益), editor. 1984. 漢字電報コード変換表 Kanji denpō kōdo henkan hyō [Chinese character telegraph code conversion table] (In Japanese). Tokyo: KDD Engineering & Consulting.

- Ministry of Post and Telecommunications (中央人民政府郵電部 / 中央人民政府邮电部 Zhōngyāng Rénmín Zhèngfǔ Yóudiànbù), editor. 1952. 標準電碼本 / 标准电码本 Biāozhǔn diànmǎběn [Standard telegraph codebook], 2nd edition (In Chinese). Beijing: Ministry of Post and Telecommunications.

- Ministry of Post and Telecommunications (中华人民共和国邮电部 Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Yóudiànbù), editor. 2002. 标准电码本 Biāozhǔn diànmǎběn [Standard telegraph codebook], 修订本 xiūdìngběn [revised edition] (In Chinese). Beijing: 人民邮电出版社 Rénmín Yóudiàn Chūbǎnshè [People’s Post and Telecommunications Publishing]. ISBN 7-115-04219-5.

- Reeds, James A. 2004. Chinese telegraph code (CTC). Accessed on December 25, 2006.

- Shanghai City Local History Office (上海市地方志办公室 Shànghǎi Shì Dìfāngzhì Bàngōngshì). 2004. 专业志: 上海邮电志 Zhuānyèzhì: Shànghǎi yóudiànzhì [Industrial history: Post and communications history in Shanghai] (In Chinese). Accessed on December 22, 2006.

- Stripp, Alan. 2002. Codebreaker in the Far East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280386-7.

- Tianjin Communications Corporation. 2004. 资费标准: 国内公众电报业务 Zīfèi biāozhǔn: Guónèi gōngzhòng diànbào yèwù [Rate standards: Domestic public telegraph service] (In Chinese). Accessed on December 26, 2006.

- Viguier, Septime Auguste (威基謁 / 威基谒 Wēijīyè). 1872. 電報新書 / 电报新书 Diànbào xīnshū [New book for the telegraph] (In Chinese). Published in Shanghai.

- Viguier, Septime Auguste (威基謁 / 威基谒 Wēijīyè) and Dé Míngzài (德 明在). 1871. 電信新法 / 电信新法 Diànxìn xīnfǎ [New method for the telegraph] (In Chinese).

- Yasuoka Kōichi (安岡 孝一) and Yasuoka Motoko (安岡 素子). 1997. Why is “唡” included in JIS X 0221? (In Japanese). IPSJ SIG Technical Report, 97-CH-35, pp. 49–54.

- Yasuoka Kōichi (安岡 孝一) and Yasuoka Motoko (安岡 素子). 2006. 文字符号の歴史: 欧米と日本編 Moji fugō no rekishi: Ōbei to Nippon hen [A history of character codes in Japan, America, and Europe] (In Japanese). Tokyo: 共立出版 Kyōritsu Shuppan ISBN 4-320-12102-3.

External links

- Chinese Commercial/Telegraph Code Lookup by NJStar

- 標準電碼本 (中文商用電碼) Standard telegraph code (Chinese commercial code) (in Chinese)

- Unihan database from Unicode Consortium: includes mappings between Unicode and Mainland or Taiwan versions of the telegraph code (kMainlandTelegraph, kTaiwanTelegraph, in

Unihan_OtherMappings.txt).