The Tree of Peace Society was founded in 1984 and incorporated in New York State on October 17, 1994, as a "foreign" not-for-profit corporation ("foreign" a legal formality owing to tribal sovereignty considerations).[1] Its headquarters are located on the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation in Hogansburg, New York, which borders the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, Canada, along the St. Lawrence River.

Since 1984, society members, headed by founder Chief Jake Swamp have ceremoniously planted trees in significant public places, such as near Philadelphia's Constitution Hall in 1986[2] and on April 10, 1986, at Shasta Hall, California State University, Sacramento, California[3] The organization's official website explains the ancient Native American legend behind the group's work:

The Great Tree of Peace [of the] Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy -- Over a thousand years ago, the Peacemaker...Aiionwatha (Hiawatha) brought the Great Law of Peace (Kaianerekowa[6][7]) to the warring Indian nations of what is now New York State. The message of Peace, Power, and the Good Mind resulted in the forming of the Haudenosaunee Iroquois Confederacy. The league of nations consisted of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga,and Seneca, and later the Tuscarora. These nations were instructed to bury their weapons of war under the Great Tree of Peace, and to unite as one to uphold the Great Law of Peace by joining "arms" so that the Tree of Peace would never fall.[8]

The educational website Past is Prologue[9] contains an article explaining more about how and why Trees of Peace are planted by the group:[10]

...Chief Jake Swamp of the Mohawk Nation and co-director of the Tree of Peace Society travels around the world planting Trees of Peace, including on the Smithsonian Mall during the Bicentennial celebration in honor of the contributions to the U.S. Constitution which came from the Iroquois Great Law of Peace. Such traditional ceremonies cannot, of course, be replicated by non-Iroquois...Suggestions for Ceremony: Call the group together with music. If a Native American drumming (much of which is sacred) group is available in your area, this would be appropriate. Form a circle around the tree. Readings could include The Great Tree of Peace from Three Strands in the Braid: A Guide for Enablers of Learning ...Select two items to be buried under the roots to symbolize national unity and peace. In the original ceremony, weapons of war were buried...

(Another book by the author of Three Strands in the Braid features cover art depicting Benjamin Franklin sitting under a Tree of Peace and negotiating with a chief in the Iroquois Grand Council.)[11]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/3Views:2 2827 3603 102

-

Preamble to the Republic: Condolence, Wampum, and the Language of Peace

-

The 1st Financial Tree Of Life -By Qasim Ali Shah (Rotary Club of Lahore) (In Urdu/Hindi)

-

Muslim Imam Anjem Admits Islam Not a Religion of Peace

Transcription

DR. JOSE BARREIRO: Welcome, everyone. Welcome every one of you, and welcome to the Swamp family, Jake, Judy, Skahendowaneh. We're so happy to welcome you to the National Museum of the American Indian, and we're honored today by the presence of such a distinguished American Indian family, a distinguished Haudenosaunee family. So thank you so much for coming. This is a family of people that get out a lot, speak a lot. Jake has been all over the world especially, Judy as well. Skahendowaneh's starting to fill in the miles as well. Jake Swamp served on the Mohawk Nation Council for nearly 40 years and was called upon to travel the world, representing Iroquois diplomacy of contemporary times. Also, he and Judy and family founded a major international NGO, the Tree of Peace Society to carry the message of peace of righteousness to the four corners of the earth. They are well-known people, but still we are very privileged today because it is always a rare opportunity in a place like Washington, D.C. who hear from traditional people who live the life, reside in a Native community. In this case, the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne, and are part of an ancient Haudenosaunee way of life that persists into the contemporary institution of the Longhouse. So welcome, Swamp family. We're honored by your visit. The six nations, also known as Iroquois, of course use their own indigenous name, Haudenosaunee, meaning people who build the Longhouse. They are the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora, Cayuga and Seneca. Together, they comprise a population of perhaps as many as 100,000 or so. Hard to know these census figures, what's accurate and what isn't, 100,000 people residing in some 17 reservations and territories, mostly in the geography of what is now known as New York State and the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario, and also with reservations in Wisconsin and Oklahoma. Influential way beyond their numbers, the Haudenosaunee developed, as the late Seneca scholar, John Mohawk liked to put it, a way of life that is a thinking tradition. That is an intellectual tradition based on a clear perception of the world, translated into a philosophy of life. Jake Swamp and his family naturally represent that philosophy, which is embodied in a classic, human, oral and now written document called the Great Law of Peace. Among the American founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin wrote about these early treaties about the marvel of the forest diplomacy they represented, and went on to publish a book of early colonial protocol, represented by the six nations. Consistently, as we read the words of the interpreters of the early treaties, the first 200 years or so of the colony, translating the recitations of the native chiefs, we hear the introductions of the words of the condolence ceremony. Historically, this most American of diplomatic protocols was used for the last time during the 1794 transactions at the Treaty of Canandaigua, which was called for by George Washington, which in fact is known as Washington's covenant. There is much history in all of this, very rich, very American, and most importantly, very much alive. A living tradition, ongoing, creative, wise and useful. We at the National Museum of the American Indian again are honored to present the Swamp family and their messages because it appears very much that the world needs to hear such messages. Some of you had an earlier description of the program. We're going to reverse the order to start with the younger generation, then ask for words from the woman's side of the house, and then go to our main speaker, Chief Jake Swamp, president of the Tree of Peace Society. So we're celebrating here today in particular the mounting this week of the Mohawk chief's gustowa [phonetic], or head dress of honor and position in the chief's council, which is to be found in the - - room at the entrance to our museum. It was installed this week. This circular pathway of mounted - - conveying the museum's core messages. It is a contribution of Skahendowaneh Swamp, gifted artist, gifted practitioner in the Longhouse culture, and a speaker, faith keeper of the Longhouse. Skahendowaneh was last year appointed to the inaugural chair in Indigenous Knowledge at Trent University, a new chairmanship signaled to bring worldwide attention to the university's already renowned Indigenous Studies Program. Skahendowaneh. [Applause] MR. SKAHENDOWANEH SWAMP: [Speaking Native language]. MR. SKAHENDOWANEH SWAMP: I was asked to come here today to give an explanation for a piece of my people's teachings that I've shared with this museum. As Jose mentioned earlier, there's a new display in the Potomac Atrium where traditional Mohawk loyane [phonetic], or a chief's headdress, is now available for everyone to look at. So I was asked to come here today to give an explanation of this item. But first, in our ways, whenever we gather for anything, the things that we are to do, the first thing we are to do is offer greetings and thanksgiving to each other for arriving here safely and to all of the natural world, beginning with the Mother Earth and everything that grows from her, everything that she provides to us as human beings as we walk upon this earth. Then we move onto the sky, to the sun, to the moon, the stars, the thunder beings, the winds, and we give thanks to the four sacred beings who watch over us each and every day and every night to make sure that we are safe as we dwell upon this earth. Lastly, we send our greetings and thanksgiving to our original place of being, what we call [Speaking Native language], the original place of life. That is where the creator dwells. As I gathered my thoughts on what I would say today in relation to this traditional headdress, there were some teachings that came to my mind that I wanted to share with you. I thought it was a good idea to start off with our [Speaking Native language]. First I'd like to mention where the word [Speaking Native language] comes from. That word, [Speaking Native language], what it means. That word is what we call the giving of thanks. It's central to our teachings as Haudenosaunee people belonging to the Longhouse of one family, or [Speaking Native language]. The main root word of [Speaking Native language] is [Speaking Native language]. And what [Speaking Native language] refers to is our minds. After each and every passage, I ask that everyone would gather our minds together as one, as we gave thanks to all of the natural world. [Speaking Native language], as one we will all give of this thanks. So as you notice my shirt here, I'm wearing this shirt. This is a shirt that I wore at my wedding five years ago. You see the beadwork designs that are beaded throughout my shirt. I wore this shirt specifically so I could share some teachings with you about our designs. I took a few moments, and I walked around the museum earlier, and I noticed that this design was on many items. What I wanted to share with you about this is this comes from our creation story. They call it the celestial dome. What it symbolizes here is there's a separation between the two worlds, this world that we live in here, and that place that I mentioned earlier, [Speaking Native language], the original place of life. And it's this separation. This is also a really central idea in our teachings as Haudenosaunee people. We acknowledge it each and every day of our life. This idea behind this symbol was so important to our people that we actually designed our original Longhouses after it. If you see our original dwelling places in pictures or drawings, you'll notice that our Longhouses were in a dome. The symbolism of the Longhouse is there is no door. There are no walls. There is no roof. The Longhouse is where the sun comes up, to where the sun goes down. That is the Eastern and the Western door. The ground beneath our feet is the floor of this structure, and the sky above us is that roof. So each and every day that we walk in this world, we are always in this Longhouse, and one thing that was shared with me, as a young boy and was taught to me throughout my life by my mother, who is sitting right here with us, was whenever you go to Longhouse, always have a peaceful mind. [Speaking Native language]. And so when I was growing up, I used to think about that. If I thought of this Longhouse as being a building, I would only think of carrying that good mind when I'm outside of those walls. But also growing up with the teaching of this symbolism of this Longhouse taught me to always have a good mind in everything I've done, everything I do and everything I will do because I am always in this Longhouse. This teaching comes to us from the Peacemaker, from the [Speaking Native language], which my father will speak about later on. So in relation to the gustowa, in a similar way, this symbol of the dome was also incorporated into the design of our traditional headdresses, our gustowas. And I have--I brought my own today, and I wanted to share some symbolism of this headdress, which I wear today. And in relation to that word, [Speaking Native language], our original name for a gustowa, as I was told by my cousin, Segohaneawa [phonetic], [Speaking Native language], and what that comes from is when we split the feather, how the feather curls. And when we tie all these bunches of feathers together, it is like creating a body of water upon our minds. And in relation to the tree of peace, the symbolism of the great tree of peace, some of you sitting here may have heard the symbolism, and I'll share a little bit about it. The tree of peace, the tree that was chosen to be the symbol of an everlasting peace, is the [Speaking Native language], the tree of great long leaves, or the great white pine, also known as [Speaking Native language] or [Speaking Native language]. And from this tree, there are four [Speaking Native language], or four white roots of peace that spread into the four directions. And this tree was chosen because no matter what time of year, it is always green. And the symbol of this is that no matter what time of year, no matter what year, no matter what day, there will always be an everlasting peace. So today, I was wandering about, and I was exploring this place, Washington, D.C., and I took my children to a location where this white pine is planted. It was 22 years since I had been there, and 22 years ago, my father planted a tree next to the Vietnam Memorial Wall. You'll notice, if you look closely, there's one lonesome white pine growing there, and it's to remind us of this peace, and I couldn't help but see all those names on that wall that were sacrificed in the name of war. I looked to my right, and I seen that white pine growing there. That's what I wanted to share with my children, and that's what I wanted to take back from that place, which I had not been since 22 years ago, when I was here, when it was planted. So it was a nice place to come and revisit. So another symbol of this tree of peace is that this tree was uprooted. They say it was a young tree in its beginnings, and this young tree was uprooted, and in the crevasse that was created by uprooting this tree, the weapons of war were placed beneath the roots, and the symbolic river or this body of water was to take all of those weapons of war away from our people forever. So in a similar way when we wear these gustowas, those bad things that we may have on our minds, the negativity that we may be carrying, grief, sadness, when we wear these headdresses, those things can be washed away in a symbolic way. So for that reason, I'd like to use the white feathers in my own gustowas. I've incorporated it into my own headdress that I'm wearing today as well as the one that is now in the gallery. The other symbolism of it is that in the [Speaking Native language], or the five nations, there are the [Speaking Native language], who are where I come from the People of the Flint, the [Speaking Native language], the people of the Standing Stone, [Speaking Native language], the people of the hills, [Speaking Native language], people of the mucky land, [Speaking Native language], people of the great mountain, and then in the 1700s, the [Speaking Native language] joined our confederacy, following those great white roots of peace. Each of our headdresses are different. For the [Speaking Native language] people, our headdresses have three feathers upright. The [Speaking Native language] have two feathers upright and one down. The [Speaking Native language] have one feather up have one up and one down. The [Speaking Native language] have one feather down. The [Speaking Native language] have one feather up, and the [Speaking Native language] don't have a feather. Another teaching that I got from my mother when I was inquiring about this, my young mind when I used to ask a lot of questions, and she told me, each of our nations around this world, everywhere, we have special headdresses that symbolize who our people are. I asked her, how come our gustowas are different? How come there our war bonnets? How come there are many different headdresses that you see? She told me that that soul [Speaking Native language] will know who you are when you pass on from this earth, and you will know what your nation is when you live in this world. So these things were taught to me at a young age, and so today, it was a very nice feeling to be able to go and visit that place that I had helped plant that tree so many years ago. So now I'd like to--are you going to introduce--I'd like to introduce my mother. She's going to speak a few words. [Applause] DR. BARREIRO: Thank you, Skahendowaneh. I just wanted to say that Judy, as the woman, is the heart of the family. Lifelong participant in Mohawk traditional culture from a long lineage of women leaders, healers and clan mothers. Again, I think we're privileged today to have a person like Judy Swamp here. In a culture where the women have the special responsibility to select and place and impeach the men chiefs, I asked Judy to talk about the qualities sought for in choosing and training and expectations of leaders among the men and chiefs. Judy? [Applause] MS. JUDY SWAMP: [Speaking Native language]. My Mohawk name is [Speaking Native language], which means I take the leaves off the trees. My English name is Judy. I'm not going to say the last name because that's something that was given to us later on in life where we had to take our men's last names. But the one thing that I would like to talk about is our women and how important they are in our society. The women are the ones that gave birth, and we should be put up in high esteem for that, but we also, as women, have to give a lot of respect and show a lot of respect so ones coming up in the future will see that and try to follow that way. I was brought up as a Longhouse person, [Speaking Native language], and for many years growing up, I remember all the times that my mother would say, you stay around the house. I would always find a way to get away and run barefoot toward the river where my uncle resided. Because the way we grew up, my father was a farmer. He was a hunter. He was a fisherman, and he was also an ironworker. So he was home till we put the gardens in, and then we would be gone away to work. So we spent a lot of time with our uncle. He was a single parent. What I remember the most was how during that time, as a little girl, I was always one that was never satisfied with one answer. There had to be several, but I didn't debate with him. I somehow took all his teachings to heart, and he taught me a lot. He talked of the creation story, and he also told me, he says, you know, I know you came here without your mother's permission because if you had come here with her permission, you would have shoes on. And so there was no way that I could get around him, but he let me stay. He said, your mother will be expecting you back in less than an hour, so you make sure that--I don't want to hear no arguments, but I would like for you to go home. He says, I'll walk you back. I remember at that time, I must've been only about five years old, and his house was the usual. You know, the road going to the neighbors or to family members. But I remember even back then, that it was years later that I asked my mother, I said, why is it that I keep feeling that I was there when my uncle got - - as a leader? And she looked at me, and she says, no, you couldn't have been there. I said, but then I--then I started to tell her what I had seen. She looked real shocked at me, and she didn't listen. She didn't ask any questions, and I told her a story of the condolence of my uncle. His name was Skahendowan, his Mohawk name, but his title name was [Speaking Native language]. She told me, she says, you know, we have been told these things, that they do happen. She said, I was pregnant with you. You were not born yet. She says, your uncle was - - in June, and you were born in August, but yet, I saw what was going on. I even described the old stove they used to cook the corn soup. I remember the women with shawls on that start to hug and they start to cry. And I asked her about it, and she says the reason why they cry was that they know hopefully in the far future, that there would come a time when it would be a hardship to - - somebody, that the ways of our people had started to die out. She says, I think the reason you were shown this is that you have to keep that alive. So today, as I stand here, I'm thinking of the role we have as people of a clan. Some of our people, our family clans are here, and one of them is - - and her boys, and I am proud to know that they are here to share this day with us. One of the things that we do know is as women, that when we go and search for a leader, it doesn't take a day. It doesn't take a year. It takes a while because you look at so many things, and to me, it's always been the most important to make sure that we get somebody who's honest, a person who's compassionate, a person who is fair, and will not only allow favors for his family, but that he will deal with things fairly, and a person who has to be of the right clan. And there's I guess the thing is that the person has to be a very good person, and he has to be a very good family man because when he is in as a leader, he has to look at his whole clan as his family. So for 37 years, 38 years, my husband was asked by my mother if he could take that role because he's Wolf clan, to take that role and sit in as a leader for us until we found somebody. I think what we did is I think we went to sleep because we found that he's a fine man, and when he went in, we left him in there for 37, 38 years. But the reason that then we had to look for a clan mother. My mother was a clan mother, and she had been put in not very many years after my uncle was. We always looked at ourselves, the daughters of our mother, that we were her arms and legs. When she needed things to be done, she would look around, and she would say, can you do this for me? I need to get a hold of this. So we all got used to as a family to look out for our mother and help her out. Eventually she became sick, so she had to look around. She had to review her whole family life. Who would be the next clan mother? Who could take care of this family because you don't only look at your family in your home. You look at your whole clan, and that's a big difference, especially today when we have thousands of people in the Mohawk nation. It's almost impossible to be able to look at each and every one. But you always welcome your clan with open arms. Sometimes disagreements come about. You forgive, you forget, and you go on because we know it's not a good example for the little ones. So when that happened, that she became ill and she could no longer continue her role as a clan mother, I remember that day when she called me, and she said, are you busy today? I said, not really, what did you want? She says, can you come over? We're not exactly that close in distance, but it was my mother, so I went. And she kind of looked at my father. She kept looking at the door. Finally, he got up, finished his tea and he went out. She looked at me, and we both sat down, and it took her a while, and I just give her that time because I wasn't sure what she wanted to say to me. What she did was she told me how she had become ill. She says, you all know that I've become ill. I've been in and out of the hospital. She said, I have a heart condition that won't ever really get better, and eventually I'll be gone, and she says, I want you to accept that. She says, but before I go, I have a big job to do, and that is to put somebody in my place. She says, I have a lot of daughters. I have taught you well. Some of you are eligible to fill that space. I just looked at her, and I kind of had an idea who she was going to choose. So she started by my oldest sister, and she said, your older sister is already married to one of our leaders of the Turtle clan, and I can't really ask her because she's already got a full time job on her hand. She said, the next one has become Catholic, and the people would not accept her. Our clan would ask questions about it. She went down, and when she got to me, she looked at me and smiled, and she said, the reason why I more or less shooed your father out was that him and I had a debate since 7:30 this morning. We've been debating. She says, I cannot understand that you and him kind of butt heads quite a bit, and yet, she says, when I told him what my plan was, he says, I'll tell you what I think, and she just listened to him. He says, I think the best one would be Judy, and she says, it really shocked me because you and him can never see eye to eye on things. Why this time when it's a big responsibility, and I asked. I said, could it be that he wants to punish me once and for all? And she says, I don't think so. She says, he was very serious. Yet I knew as I sat there who she was going to choose because when she got to her, she says, how many times have I walked the road from here to her house down the road? How many times have I walked in her home and they'll be eating because it's haying time? And there would be all kinds of boys there. She says, I'd look at each one of the boys, and they'll smile, somewhat shy and kind of - - turn away, and I would not always know who they are, but your sister make them welcome in her home, no matter if there's 20 boys. She would feed them all, and some would even stay overnight because they were there to help because that's what her and her husband did. They had a farm. And their table was always set for more than the eight children that she had. So she didn't tell me then that she was going to choose her. She just told me that the reason she disagreed with my father was that she says, you tend to--she said it in Mohawk. [Speaking Native language]. I always try not to laugh about it when I think of that word, and what that means is--the only way I could translate it is fanciful. That I would always look for the brighter colors or something that's shiny, and she says, it's not really a good thing to teach your people, to all walk around in all fanciful was how she said it. I just smiled at her because I knew myself and I know she knew me well, too. She says, I'll tell you one thing. I don't want you to feel bad because I will put one of your sisters in this position. I thought, how could I feel bad when you just lifted the world off my shoulder? And she sat there, and she always not real, real serious, but she always had this calm look about her. She looked at me, and she started to cry. I told her, don't cry. I think you're making the right decision. What she laughed at me was that I knew and I mentioned my sister. She says, how did you know I was going to choose her? I said, because it's the one who's most suitable. But what happened as time went on was that she tried for 12 years to get us together. We have to get somebody to take that position. I took it temporarily. She says, it's a lot of work. I don't see you coming together to help as much as all of you should. I said, all you had to do was ask. She said, I shouldn't have to ask. We grew up with the same teachings. We have to all come together and work together as one. Then I think back, and I thought of our mother's words of--she said it many times of the kind of person that a man has to be before he can be that position, and she told us, never make the mistake of putting a man who does not have no family in that position because the reason why they're so strong in family is that when you have a family, you more or less learn yourself without being told that you look out for everybody else's children. If they're there, and it's time to eat, you don't send them home. You call them in and invite them to eat with you. If they have a dirty face, you reach out, get a wet cloth, wipe their face. If their hair needs combing, you do it. She says, that's what we are as women. That's our role. That's the most important role, that we always look after the children and we never let them cry. She says, never let them cry in pain. Today, as I look around me, I find that we are in that position, that the children are crying because there's so many changes in our lives. So many things have come about in our communities that myself at this time, I'm kind of--I don't know quite how to describe how I feel. Kind of numb for a while, but I know when - - my mother used to say, if I decide something, if I'm sitting down, I get right up, and I'm off running. And that's the reason why she didn't choose me was that she says you might sometimes forget that you owe this family. You owe your whole family the good things in life, and if you run too fast or move too fast, you tend to forget some things. So the day came when our sister told us we have to make a decision. We have to put a clan mother in place, she says, because I don't think I can continue. So they all turned around and looked at the other sisters, and our other family members, our cousins. We invite a lot of them, but a lot didn't show. And they point to me. And I thought of my mother, and I thought, all those years, she did teachings for us so quietly that she never made it seem like work, but all of a sudden, I felt like I shrunk about two feet, just a little person. But I didn't want to disappoint anybody, so at that time, I accepted. Later on, was two things that made me pull back, and one of them was that in my job, one of the things I was doing was teaching the culture to the students, the many students. And this young girl got up, and she asked me, she says, you know, she says, I look forward to your teachings every time you come in. But the one thing that hurts me, and she started crying, was that if you accept that role as a clan mother, she says, I don't think I could forgive you for it. I just looked at her, and it hit me, that what she was saying was true. She might have been only 16 years old, but she was telling me a truth that I had not even really considered and looked at. That was that Jake and I are from the same clan, and we're not even supposed to be married. People of the same clan do not marry. And it hit me. I felt like somebody punched me in the chest, and I looked at her, and I could feel the tears, but I smiled and I thanked her for reminding me. She just looked at me, and she says, you mean I'm only 16, but you're going to listen to me? I said, I have to because you're telling a truth I have forgotten. So those are the many things that we learn and that we are taught. In how to pick a good man. They say you always look at the person who's always out there, always helping others. He does not only take good care of his family but take good care of anybody who's around. If help is needed, you don't have to go in and ask him to help you. He'll come. He says, those are what we call the natural leaders. Don't overlook that. Don't be choosing somebody who comes waltzing in with his ribbons and big headdress. You know, looking around, trying to get attention because he'll fail you. Always look for those quieter ones, the ones who think deeply, the ones that always think of the future, and doesn't dwell on the past. So I guess that's what we did when my mother had picked Jake. We kind of overburdened. And the one thing that I have to share is how it was being his wife and during those years, I became almost a mother and father in our home, but I'm determined, even now, I'm a very lucky woman for all the times that the door opens and one of my sons or daughters will walk in because they're very much at home, and it still has open doors. So I think it's time for me to give up this time and have Jake take my place. [Applause] DR. BARREIRO: Thank you, Judy. That's wonderful. It's the real thing, huh? Well, Jake has informed me, and as the family has mentioned, he no longer sits on council. He's been released from council after 37 years, but I still call him chief. I've known Jake Swamp as the chief of the people since 1976, nearly 35 years, and I don't think I can call him otherwise. Jake, I remember you during the dangerous, proud and difficult days of the Racketpoint [phonetic] encampment back in 1979 to '81 when the Mohawk women asked their chiefs to stand up for their sovereignty in the face of 400 trooper and vigilante rifles, and how you worked so diligently to bring that crisis to a peaceful end. I think that's been your job, your role, your duty, many times as it is for all of the council chiefs of the Haudenosaunee. I remember you in Geneva and Rotterdam and other places where you have stood for the people, and since then, you have circled the whole world, planting millions of trees and teaching millions the Haudenosaunee message of peace. For that, I'm very proud to call myself your friend. Please welcome Chief Jake Swamp. [Applause] MR. SWAMP: Thank you, Jose, and I want to thank everyone for coming out today. I guess I lost two inches in height when I broke my back years ago. Afterwards, I shrunk two inches, and I'm always complaining about my long pant legs. Judy's always fixing them. Today we're here to talk about the great law of peace. It is so evasive, meaning the peace in our world, and we need to come to terms with how do we bring our world together into one body, one heart, one mind. It is very extensive to talk about the great law of peace. We went on a pilgrimage one time, which I led a group of people from the Grand River, and elsewhere. We took along some busses, and we went back to where the peacemaker was born, and we did the history. It felt so good to walk and to go to the places where the peacemaker had been. Knowing at the same time what a terrible life he must have led because beforehand, there was so many areas of violence that were happening. The things that he had to encounter. When I think about those things, I think about today, our world today. And back in 1984, I decided to go out into the world, planting trees of peace because this would give me the opportunity to talk about the great law of peace in front of different audiences that may be able to listen. Mainly to gain new experiences of how do we come to terms with what's happening in our world. And I have come to the conclusion that our world and its people have 80% in grief because people in grief experience different things in life. For one thing, symbolically, when we have a great loss, it brings tears to our eyes for our vision. And when we are teary-eyed, we have a blurry vision, not being able to recognize what's in front of us. Secondly, whenever we experience a great loss, our hearing becomes stopped. We cannot communicate clearly any longer, for our mind is positioned on our losses. Therefore, it is hard to hear under those conditions. When we suffer a loss, it is hard to speak because something grabs us in the throat. And it lives there. And it's hard to speak because of that. So early on when we encountered the new people that came to this land, they were carrying much grief in arriving here. Things had happened where they came from. They were running away to find a new way of life. So our ancestors were pretty knowledgeable about feelings. So as these people and our people started to make agreements of how they're going to live together, they used to always spend some time to address the areas of pain. And they would say, our brothers, we haven't seen you in a very long time. Perhaps you may have encountered an experience of loss in your life. But we cannot have an agreement unless we have clarity between us. And so that's what they did. We call it the three areas that must be covered, and that will bring clarity to everyone. They say, we take you by the hand, and we reach to the sky. And we bring forth the purest cloth that we could find. We'll bring it to you, and we will wipe away your tears. So that your vision will be restored for the future. Then after they finish that, then they'll go to the next one. They'll say, our brother, we'll take you by the hand, and we will reach to the heavens, and we will find the purest and softest feather that we could find, and we will go to your ears, and we will move the [Speaking Native language] of grief from your ears. Ask the great creator above to stand with you as the new sun rises tomorrow. That everything that makes noise in the world will come to you again. The birds, as they sing their song. The wind as it whistles through the branches in the leaves. You will hear that again. That is important. Then he said, now, our brother, this is another. He said, when you experience a loss, it takes away your voice for something gets stuck in your throat, and it's hard to speak. Therefore, it's hard to communicate. He said, this is what we're going to do. We're going to reach to the heavens up above, and we're going to find the purest water, and we're going to bring that for you to drink. This pure water will wash away that lump in your throat, and we'll ask the great creator in the universe to give you the power that tomorrow morning as the new sun dawns, you will stand there, and your voice will be restored. So those are only three areas, but there are others that we have, especially when they raise leaders, new leaders in our nation. And so I have found in my travels that indeed there is about 80% of our people in grief, not knowing, not noticing that they are carrying this from day-to-day. Till it has consumed them, and it begins to become a great burden upon themselves. And so what do we need to do? Using the great law of peace and its teachings, I share that around the world. And I try to bring comfort to people who are in distress, for when people talk about the condolences, they suddenly become aware of where they have been and where they need to go in the future. So I've been very fortunate to learn these values and traditions through the - - teachings that are constantly being recited by the elders. Now it's our turn. People my age, it's our turn to teach our youth. And I think my son here has done a very good job in learning, and I think we all, both of us owe it to my wife, Judy, who has had the strength to teach us everything she learned because for me, I did not grow up with it. I was a colonized person. And I had to go through much pain to find myself again. But that's behind me now. Today, I'm working on a big project whereby we're going to invite all the indigenous people to the Mississippi River in 2012, and I just got back from Ecuador last week. I shared this knowledge with native leaders, the Mayans and the - - and the native leaders in South America. They liked this idea of congregating on each side of the Mississippi River where we will carry on a very great condolence ceremony to address the pain of the past 500 years. For there is a teaching, - - condolence says, when you put somebody in the ground, of course there's a mound that is created as you're walking away. They say do not look back when you turn around from the grave. As you walk away, look back into the future, do not look back for you cannot change what's happened. This is how we look at indigenous people. We're walking like that. We're walking sideways, trying to look back all the time. So when we live like that, it's hard to share our gifts, our knowledge between each other. We're all isolated in our different places, and we need to come together as one people again. So that is the message I brought to Ecuador, and it will become known pretty soon what is going to be happening. The others in Canada have already accepted the challenge. We're going to the Arctic north. So today we busy ourselves using the great law of peace, and there are other teachings in other cultures amongst the indigenous people. They're very closely linked. Together we will start to share our knowledge with one another. The Tree of Peace has been described, it's true. The greenery represents the peace and never loses color through the seasons. The four white roots go in four directions, which means it's going to spread the peace into the four directions, to whoever may listen. The greenery of the tree and its branches and it's - - , there are needles hanging on there with five tied together. This is where the idea came from, to bring together the United States. The symbol of the five nations tied together into one heart, one body, one mind was the teaching that was given to the leaders who were putting together the Constitution of this country. Hardly anyone knows in our country where the ideas of democracy came from. It came from that place, the original tree of peace. The original tree of peace was applied to John Hancock. They called him [Speaking Native language] because he understood the principles. So they decided to give him that name, meaning Big Tree or Sturdy Tree. [Speaking Native language] gave a speech in 1744 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and he was showing the colonial leaders how to form themselves into an organization, and he was saying, such as ours for we have been practicing this way for generations and generations. Why can't you do it the same for yourselves because it is easier to settle problems when you talk to one another, not when you bicker because the colonial leaders were usually in conflict to one another. So when Benjamin Franklin went back to Albany, New York, 1754, they called it the Albany Plan of Union, and the six nations went there with their belts. And they explained to them once again. So you can trace how the independence movement kind of started. By 1775, it was really evident that these people are going to break away from their mother country, and they're going to form themselves into an organization, such as what we have today as United States government. I cannot stop there because when we look at the United States government, it is very young. We have to look at the United States as we would look at a 17-year-old boy that tends to get in trouble sometimes. So that's the way we look at the United States. There's another thing, too. I was approached by a person in India. He's a lawyer, and he purchased one of those books, and he said, now I know where democracy really came from. He went around back into India, and he asked the judges and the lawyers, the circle he wanders around in, and he asked them, do you know really where democracy came from? No one knew, and that blew his mind. He e-mailed me, and he said, nobody knew where democracy came from, and we're going to help you now. We're going to let the whole world know. He said, there's 221 countries practicing democracy, and no one knows where it came from. So we have to let them know. It's true, we've been kind of left out of history. We have come this far, and people in general need to know these principles and ideas. That way, we can all feel good about ourselves and go into the future and build a real good future for our children. We always have to talk about our children that's our future. We always talk about the future generations, wherever you go, where Native people are, they're always doing that for their children, and their children. Seven generation concept. That's a law that's been given to Iroquois leaders. You must think seven generations ahead before you make a decision. What does that mean? It means we're bringing security to the children that will be born into the future. So that they may enjoy what we enjoy today. We have to be careful how we live on Mother Earth, for our elders told us that certain things are going to occur. Sometimes in our lifetime, sometimes in the future. Many warnings were given and today one of them have come true. The oil is leaking in the ocean. In the Thanksgiving address he gave us today, it says to the thunder beings, we thank you for the water you bring to us to quench the thirst of the earth. We also thank you for withholding those things under the surface of the earth that were put there by the creator so that if they should ever surface, they would bring much damage to the world. In other words, when we dig up uranium and different things out of the ground, we don't know what we're doing that's going to cause us many, many heartaches and pains. So we have to listen to the elders who have been given the instruction, what to tell the people. We have been given the prophecies, but when we talk about it in the public, sometimes they say that's old wives tales. Well, when the truth hits, that's when people become wary. You don't know how many phone messages I have received already. Please come to this gathering. We need your help. Talk about your prophecies. Talk about your culture. People don't know. But one of the safest and easiest way to prevent this is to go by the teaching that we were given as children. They said if you ever arrive at a river or a stream, and you're thirsty, you have your cup in your hand. Do not go directly to that water to get your water. Look at the water first and see which direction it flows. After you have determined that, then take your container and you always dip with the current, in the direction of the current. Do not ever dip against it, for it will come back on you. So that's a teaching we follow. In anything we do in life, if we go with nature's current, we will never get into trouble, and we can go on and on and on in our way of life. We have done so many things against nature. [Loudspeaker announcement] MR. SWAMP: I guess we're getting close to that time. I sometimes compare myself to them toys where you wind it up, and I'm kind of used to standing up here for a couple hours, but I guess what we can do with the remainder of our time is maybe we can ask for a question period. Maybe someone has a question, maybe a lingering question. That's a response I always get. [Laughter] FEMALE VOICE: When you go to these other countries around the world, are you invited there by their government, or - - ? MR. SWAMP: In this case, I went to Ecuador, we went to visit the volcanoes. Recently one went off, and that's where we went. We went there to do ceremonies to acknowledge the volcano because this kind of activity is saying to us, you better acknowledge us. So we went there to be thankful to that volcano. We know that's where life came from. We acknowledge that, and we left gifts and things to there for the volcano. A very funny thing happened. It was kind of something that there was an elder from Mexico. He had this contraption in his hand, and as he was praying--when we got there, it was all covered with clouds. So as he was praying, then the clouds started to split, and it opened up. The whole volcano, we could see it. When he finished his prayer, then the clouds come back together. I knew what it meant, that the volcano accepted our gift, but the volcano covered itself again saying you better go and get to work. So that's how I understood that. The only thing that's happening is I had pneumonia before, and I had a hard time breathing. So I couldn't go on some of those trip that went way up. But we got her done. MALE VOICE: Have you decided where you're going to be holding your - - ? MR. SWAMP: No, we left it up to the Ojibwa people who are the caretakers on the waters and might be in that area. Yeah. MALE VOICE: - - MR. SWAMP: Thank you. FEMALE VOICE: - - MR. SWAMP: Yeah, right now we're working on MR. SWAMP: Yeah, right now we're working on that problem, hydro fracking. Yeah. And it's a very bad thing that they pour that water down there. So that's what I mean about how we're doing things in life. We're going to spoil the earth, or we're going to destroy ourselves if we don't be careful. We just have to go out there and teach and keep teaching. One more. MALE VOICE: - - MR. SWAMP: It happened prior because the Seneca people liked war so much that the peacemaker needed to give them a sign so that they could become believers. So there was a total eclipse for three minutes, and they traced that back, the astronomer traced that back to 1142. It was in the afternoon in August. I forget what day it was. FEMALE VOICE: - - MR. SWAMP: What happened with that is the Iroquois nations, as a confederacy, remained neutral. Then different people came from British and Americans, enticing young men to join either side. But the agreement then had was they would not kill each other if they met in battle. But it happened in Eriskiny [phonetic], Battle of Eriskiny, and it was very bad. So I want to thank all of you for being patient. Thank you. [Applause] DR. BARREIRO: Well, I want to thank everyone. One always hates to put a timeframe on elders' speaking, and this kind of an event always calls for some limitations. I want to reiterate again that the condolence ceremony that Jake and family spoke about was the primary protocol of treaty making for 200 years, through the 1700s and the 1600s, and it was used finally in the last Treaty of Canandaigua. The oral tradition that we see, and I won't read it now. I'd hoped to be able to, but in a book that Franklin published of the treaties of that time, there are excerpts from father to son to remember, and there's an excerpt to the British at one point where they speak to the fact that even though it may seem to the British that the Iroquois were not remembering and did not have writing and so they would forget these treaty provisions, that in fact then the speaker goes into the philosophy and the practice of oral tradition and the importance of getting it right. I'm just very thankful and very honored to see a family that got it right. Thank you very much. [Applause]

References

- ^ New York Department of State data: "Current Entity Name: TREE OF PEACE SOCIETY, INC. - Initial DOS Filing Date: OCTOBER 17, 1994 - County: FRANKLIN - Jurisdiction:DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA - Entity Type:FOREIGN NOT-FOR-PROFIT CORPORATION...

- ^ The Great Law of Peace: New World Roots of American Democracy, by David Yarrow, September, 1987

- ^ "TREE OF PEACE. Dedicated by Chief Jake Swamp of the Mohawk Nation, April 10, 1986. "When I look at this tree, May I be reminded that I laid down my weapons forever."

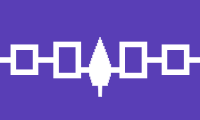

- ^ "From beads to banner". Indian Country Today. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ "Haudenosaunee Flag". First Americans. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ Kaianerekowa Hotinonsionne – The Great Law of Peace of The Longhouse People

- ^ "White Roots of Peace, Mohawk Nation; Kaianerekowa Hotinonsionne - The Great Law of Peace"

- ^ 'The Great Tree of Peace' (explanation) © 2010 Tree of Peace Society

- ^ "The Past Is Prologue Educational Program (PIP) is a program that teaches students the procedures involved in operating a democratic government. It facilitates critical thinking and governance. PIP uses three Native American Learning Stories from an Iroquois tradition to teach students..."

- ^ PLANTING A TREE OF PEACE, author unknown, retrieved 07-24-2010

- ^ Paula Underwood, 1997: Franklin listens when I speak: tellings of the friendship between Benjamin Franklin and Skenandoah, an Oneida Chief