This Timeline of European imperialism covers episodes of imperialism outside of Europe by western nations since 1400; for other countries, see Imperialism § Imperialism by country.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:5 939 3681 011 7152 893 666635 69841 700

-

Imperialism: Crash Course World History #35

-

What if European Imperialism Never Ended?

-

Colonization of Africa - Summary on a Map

-

A Brief History of The Scramble For Africa

-

Early Modern Europe Explained in 11 minutes

Transcription

Hi, I’m John Green, this is Crash Course World History and today we’re going to discuss 19th century Imperialism. So, the 19th century certainly didn’t invent the Empire, but it did take it to new heights. By which we means lows. Or possibly heights. I don’t know. I can’t decide. Roll the intro while I think about it... [Intro music] [intro music] [intro music] [intro music] [intro music] [intro music] [intro music] Yeah, I don’t know. I’m still undecided. Let’s begin with China. When last we checked in, China was a thriving manufacturing power about to be overtaken by Europe but still heavily involved in world trade, especially as an importer of silver from the Spanish Empire. Europeans had to use silver because they didn’t really produce anything else the Chinese wanted. And that state of affairs continued through the 18th century. For example, in 1793, the McCartney mission tried to get better trade conditions with China and was a total failure. Here’s the Qianlong emperor’s well-known response to the British: Hitherto, all European nations, including your own country's barbarian merchants, [yowser] have carried on their trade with our Celestial Empire at Canton. Such has been the procedure for many years, although our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no product within its own borders. But then Europeans, especially the British, found something that the Chinese would buy: opium. By the 1830s British free trade policy unleashed a flood of opium in China, which threatened China’s favorable balance of trade. It also created a lot of drug addicts. [you think?] And then, in 1839, the Chinese responded to what they saw as these unfair trade practices with a stern letter that they never actually sent. [opium: not a productivity aid] Commissioner Lin Zexu drafted a response that contained a memorable threat to cut off trade in “Rhubarb, tea and silk… all valuable products of ours, without which foreigners could not live.” But even if the British had received this terrifying threat to their precious rhubarb supply, they probably wouldn’t have responded, because selling drugs is super lucrative. [newsflash in any era] So the Chinese made like tea partiers, [tri-corn hats and all?] confiscating a bunch of British opium and chucking it into the sea. [This is sounding like a Hunter S. Thompson hallucination…] And then, the British responded to this by demanding compensation and access to Chinese territory where they could carry out their trade. And then, the Chinese were like, “Man, that seems a little bit harsh,” whereupon the British sent in gunships, opening trade with Canton by force. [response: "Yeuup."] Chinese General Yijing made a counterattack in 1842 that included a detailed plan to catapult flaming monkeys onto British ships— STAN, IS THAT TRUE? Alright apparently the plans involved strapping fireworks to monkeys’ backs and were never carried out. But, still... Slightly off-topic, obviously I don’t want anyone to light monkeys on fire. I’m just saying that flaming monkeys lend themselves to a lot of great band names, like the Sizzling Simians, Burning Bonobos, Immolated Marmoset. [Imolated Marmoset???] Stan, sometimes I feel like I should give up teaching World History and just become a band name generator. That’s my real gift. [Seriously, don't quit your day job.] Anyway, due to lack of monkey fireworks, the Chinese counterattacks were unsuccessful. And they eventually signed the Treaty of Nanjing, which stated that Britain got Hong Kong and five other treaty ports, as well as the equivalent of $2 billion in cash. Also, the Chinese basically gave up all sovereignty to European “spheres of influence,” wherein Europeans were subject to their laws, not Chinese laws. In exchange for all of this, China got a hot slice of nothing. You might think the result of this war would be a shift in the balance of trade in Britain’s favor, but that wasn’t immediately the case. In fact, the British were importing so much tea from China that the trade deficit actually rose more than $30 billion. But eventually, after another war (and one of the most destructive civil rebellions in Chinese and possibly world history, the Taiping Rebellion) the situation was reversed and Europeans, especially the British became the dominant economic power in China. Okay, so, but when we think about 19th century imperialism, we usually think about the way that Europe turned Africa from this into this, the so-called Scramble for Africa. Speaking of scrambles and the European colonization of Africa, you know what they say, sometimes to make an omelet, you’ve gotta break a few eggs. And then sometimes, you break a lot of eggs and you don’t get an omelet. [that's a downer of a saying] Europeans had been involved in Africa since the 16th century when the Portuguese used their cannons to take control of cities on coasts to set up their trading post empire. But in the second half of the 19th century, Europe suddenly and spectacularly succeeded at colonizing basically all of Africa. Why? Well, the biggest reason that Europeans were able to extend their grasp over so much of the world was the same reason they wanted to do so in the first place: industrialization. Nationalism played its part, of course: European states saw it as a real bonus to be able to say that they had colonies, so much so that a children’s rhyme in An ABC for Baby Patriots went: “C is for Colonies, Rightly we boast that of all the great countries, Great Britain has the most.” But it was mostly— not to get all Marxist on you or anything— about controlling the means of production. Europeans wanted colonies to secure sources of raw materials, especially cotton, copper, iron, and rubber, that were used to fuel their growing industrial economies. And in addition to providing the motive for imperialism, European industrialization also provided the means. Europeans didn’t fail to take over territory in Africa until the late 19th century because they didn’t want to; they failed because they couldn’t. This was mostly due to disease. [Disease: History's Frenemy] Unlike in the Americas, Africans weren’t devastated by diseases like smallpox, because they’d had smallpox for centuries and were just as immune to it as Europeans were. Not only that, but Africa had diseases of its own, including yellow fever, malaria, and sleeping sickness, all of which killed Europeans in staggering numbers. Also, nagana was a disease endemic to Africa that killed horses, which made it difficult for Europeans to take advantage of African grasslands, and also difficult for them to get inland because their horses would die as they tried to carry stuff. Also, while in the 16th century, Europeans did have guns, they were pretty useless, especially without horses, so most fighting was done the old fashioned way, with swords. That worked pretty well in the Americas, unless you were the Incas or the Aztecs, but it didn’t work in Africa because the Africans also had swords and spears and axes. So, as much as they might have wanted to colonize Africa in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Africa’s mosquitoes, microbes, and people were too much for them. So what made the difference? Technology. First, steam ships made it possible for Europeans to travel inland bringing supplies and personnel via Africa’s navigable rivers. No horses? No problem. Even more important was quinine medicine, sometimes in the form of tonic water mixed into refreshing, quintessentially British gin and tonics. Quinine isn’t as effective as modern anti-malarial medication, and it doesn’t cure the disease, but it does help moderate its effects. But, of course, the most important technology that enabled Europeans to dominate Africa was guns. By the 19th century, European gun technology had improved dramatically, especially with the introduction of the Maxim machine gun, which allowed Europeans to wipe out Africans in battle after battle. Of course, machine guns were effective when wielded by Africans, too— but Africans had fewer of them. Oh, it’s time for the Open Letter? [king triumphantly re-throned] And my chair is back! [must've been in shock last week, eh?] An Open Letter to Hiram Maxim. But first, let’s see what’s in the secret compartment today. Oh, it’s Darth Vader. What a great reminder of imperialism. Dear Hiram Maxim, I hate you. [Best Wishes, John Green?] It’s not so much that you invented the Maxim Machine Gun although obviously that’s a little bit problematic, or even that you look like the poor man’s Colonel Sanders. [sick burn] First off, you’re a possible bigamist. I have a longstanding opposition to bigamy. [quite a bold proclamation there, pal] Secondly, you were born an American but then became a Brit thereby metaphorically machine gunning our founding fathers. But most importantly, among your many inventions was the successful amusement park ride, the Captive Flying Machine. Mr. Maxim, I hate the Captive Flying Machine. The Captive Flying Machine has resulted in many a girlfriend telling me that I’m a coward. I’m not a coward! I just don’t want to die up there. It’s all your fault, Hiram Maxim. And nobody believes your story about the light bulb. Best Wishes, John Green Alright so, here is something that often gets overlooked: European imperialism involved a lot of fighting and a lot of dying. And when we say that Europe came to dominate Africa, for the most part that domination came through wars, which killed lots of Africans (and also lots of Europeans, although most of them died from disease). It’s very, very important to remember that Africans did not meekly acquiesce to European hegemony: they resisted, often violently, but ultimately they were defeated by a technologically superior enemy. In this respect, they were a lot like the Chinese, and also the Indians, and the Vietnamese and, you get the picture. So, by the end of the 19th century, most of Africa, and much of Asia, had been colonized by European powers. I mean, even Belgium got in on it and they weren’t even a country at the beginning of the 19th century. I mean, Belgium has enjoyed, like, 12 years of sovereignty in the last three millenia. Notable exceptions include Japan -- which was happily pursuing its own imperialism— Thailand, Iran, and of course Afghanistan. Because no one can conquer Afghanistan. Unless you are— wait for it— the Mongols. [we missed you, Mongoltage] [Triumphant return #2: best week ever!] Mongoltage It is tempting to imagine Europe ruling their colonies with the proverbial topaz fist, [ouch?] and while there was always the threat of violence, the truth is a lot more complicated. Let’s go to the Thought Bubble. In most cases Europeans ruled their colonies with the help of, and sometimes completely through, intermediaries and collaborators. For example, in the 1890s in India, there were fewer than 1000 British administrators supposedly “ruling” over 300 million Indians. The vast majority of British troops at any given time in India— more than two thirds— were in fact Indians under the command of British officers. Because of their small numbers relative to local populations, most European colonizers resorted to indirect rule, relying on the governments that were already there but exerting control over their leaders. Frederick Lugard, who was Britain’s head honcho in Nigeria for a time, called this “rule through and by the natives.” This worked particularly well with British administrators, who were primarily middle class men but had aristocratic pretensions and were often pleased to associate with the highest echelons of Indian or African society. Now, this isn’t to say that indigenous rulers were simply puppets; often they retained real power. This was certainly true in India, where more than a third of the territory was ruled by Indian princes. The French protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia were ruled by Arab monarchs, and the French also ruled through native kings in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. For the most part Europeans could almost always rely on their superior military technology to coerce local rulers into doing what the Europeans wanted and they could replace native officials with Europeans if they had to, but in general they preferred to rule indirectly. It was easier and cheaper. Also, less malaria. Thanks, Thought Bubble. So, while we can’t know why all native princes who ruled in the context of European imperialism put up with it, we can make some pretty good guesses. First of all, they were still rulers: They got to keep their prestige and their fancy hats and to some extent their power. Many were also able to gain advantages through their service, like access to European education for themselves and for their children. Mahatma Gandhi, for instance, was the son of an Indian high official, which made it possible for him to study law in England. And we can’t overlook the sheer practicality of it – the alternative was to resist and that usually didn’t work out well. I’m reminded of the famous couplet: “Whatever happens, we have got / the Maxim gun and they have not.” But even with this enormous technological advantage, it wasn’t always easy. For example, it took 25 years, from 1845 to 1870, for the British to fully defeat the Maori on New Zealand, [No John! Think Sister, Sister twins!] because the Maori were kick-ass fighters [and tattooists] who had mastered musketry and defensive warfare. And I will remind you, it is not cursing if you’re talking about donkeys. In fact, it took them being outnumbered three to one with the arrival of 750,000 settlers for the Maori to finally capitulate. And I will remind you that the rule against splitting infinitives is not an actual rule. Those of you more familiar with U.S. history might notice a parallel between the Maori and some of the Native American tribes like the Apaches and the Lakota, a good reminder that the United States did some imperial expansion of its own as part of its nationalizing project in the 19th century. But, back to Africa. Sometimes African rulers were so good at adapting European technology that they were able to successfully resist imperialism. Ethiopia’s Menelik II defeated the Italians in battle, securing not just independence, but an empire of his own. But embracing European style modernization could also be problematic, as Khedive Ismail of Egypt found out during his rule in the late 19th century. The European-style ruler celebrated his imperial success by commissioning an opera, Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, for the opening of the Cairo opera house in 1871. Giuseppe Verdi, by the way, no relation to John Green. [get it? huh, do you?] And Ismail had ambitions of extending Egypt’s control up the Nile west toward Lake Chad, but to do that, he needed money, and that’s where he got into trouble. His borrowing bankrupted Egypt and led to Britain’s taking control over the country’s finances and its shares in the Suez Canal that Ismail had built (with French engineers and French capital) in 1869. The British sent in 1,300 bureaucrats to fix Egypt’s finances, an invasion of red tape that led to a nationalist uprising. Which brought on full scale British intervention after 1881, in order to protect British interests. This “business imperialism,” as it is sometimes known, is really at the heart of the imperialistic impulse: Industrialized nations push economic integration upon developing nations, and then extract value from those developing nations, just as you would from a mine or a field you owned. And here we see political history and economic history coming together again. As western corporations grew in the latter part of the 19th century, their influence grew as well, both in their home countries and in the lands where they were investing. But ultimately, whether the colonizer is a business enterprise or a political one, the complicated legacy of Imperialism survives. It’s why your bananas are cheap, why your call centers are Indian, why your chocolate comes from Africa, and why everything else comes from China. These imperialistic adventures may have only lasted a century, but it was the century in which the world, as we know it today, began to take shape. Thanks for watching. I’ll see you next week. Crash Course is produced and directed by Stan Muller. Our script supervisor is Danica Johnson. The show is written by my high school history teacher, Raoul Meyer, and myself. And our graphics team is Thought Bubble. Oh, our intern! I’m sorry, Meredith the Intern. [vengeance is imminent] Our intern is Meredith Danko. Last week’s phrase of the week was “homogeneous mythologized unitary polity.” Thank you for that suggestion. If you want to guess this week’s phrase of the week or suggest future ones, you can do so in comments where you can also ask questions about today’s video that will be answered by our team of historians. Thanks for watching Crash Course. Remember, you can get this shirt, the Mongols shirt, or our poster at DFTBA.com. [back to the capitalism episode, eh?] Speaking of which, as we say in my hometown, don’t forget All Persons, Living and Dead, are Purely Coincidental.

Pre-1700

- 1402 Castillian invasion of Canary Islands.

- 1415 Portuguese conquest of Ceuta.

- 1420-1425 Portuguese settlement of Madeira.

- 1433-1436 Portuguese settlement of Azores.

- 1445 Portuguese construction of trading post on Arguin Island.

- 1450 Portuguese construction of trading post on Gorée Island.

- 1462 Portuguese settlement of Cape Verde islands.

- 1474 Portuguese settlement of Annobón island.

- 1470 Portuguese settlement of Bioko island.

- 1482 Portuguese construction of Elmina Castle.

- 1493 Portuguese settlement of São Tomé and Príncipe.

- 1510 Portuguese conquest of Goa.

- 1511 Portuguese conquest of Malacca City.

- 1517 Portuguese conquest of Colombo.

- 1556 Portuguese colonization of Timor.

- 1557 Portuguese construction of trading post in Macau.

- 1556-1599 Spanish conquest of Philippines.

- 1598: Dutch established colony on uninhabited island of Mauritius; they abandon it in 1710.[1]

- 1608: Dutch opened their first trading post in India at Golconda.[2]

- 1613: Dutch East India Company expands operations in Java.[3]

- 1613–20: Netherlands becomes England's major rival in trade, fishing, and whaling. The Dutch form alliances with Sweden and the Hanseatic League; England counters with an alliance with Denmark.[4]

- 1623. The Amboyna massacre occurs in Japan with execution of English traders; England closes its commercial base opened in 1613 at Hirado. Trade ends for more than two centuries.

- 1664. French East India Company Chartered for trade in Asia and Africa.[5]

Colonization of North America

- 1565 – St. Augustine, Florida – Spanish[6][7]

- 1604 – Acadia – French[8]

- 1605 – Port-Royal – French; in Nova Scotia

- 1607 – Jamestown, Virginia – English; established by Virginia Company

- 1607 – Popham Colony – English; failed effort in Maine

- 1608 – Quebec, Canada – French

- 1610 – Cuper's Cove, First English settlement in Newfoundland; abandoned by 1820

- 1610 – Santa Fe, New Mexico – Spanish[9]

- 1612 – Bermuda – English; established by Virginia Company[10][11]

- 1615 – Fort Nassau – Dutch; became Albany New York

- 1620 – St. John's, Newfoundland – English; capital of Newfoundland

- 1620 – Plymouth Colony, absorbed by Massachusetts Bay– English; small settlement by Pilgrims

- 1621 – Nova Scotia – Scottish

- 1623 – Portsmouth, New Hampshire – English; becomes the Colony of New Hampshire

- 1625 – New Amsterdam – Dutch; becomes New York City

- 1630 – Massachusetts Bay Colony – English; The main Puritan colony.[12]

- 1632 – Williamsburgh – English; becomes the capital of Virginia.[13]

- 1633 – Fort Hoop – Dutch settlement; Now part of Hartford Connecticut

- 1633 – Windsor, Connecticut – English

- 1634 – Maryland Colony – English

- 1634 – Wethersfield, Connecticut – First English settlement in Connecticut, comprising migrants from Massachusetts Bay.[14]

- 1635 – Territory of Sagadahock – English

- 1636 – Providence Plantations – English; became Rhode Island* [15]

- 1636 – Connecticut Colony – English

- 1638 – New Haven Colony – English; later merged into Connecticut colony

- 1638 – Fort Christina – Swedish; now part of Wilmington Delaware

- 1638 – Hampton, New Hampshire – English[16]

- 1639 – San Marcos – Spanish

- 1640 – Swedesboro- Swedish

- 1651 – Fort Casimir – Dutch

- 1660 – Bergen – Dutch

- 1670 – Charleston, South Carolina – English[17]

- 1682 – Pennsylvania – English Quakers;[18]

- 1683? – Fort Saint Louis (Illinois)- French;[19]

- 1683 – East New Jersey – Scottish

- 1684 – Stuarts Town, Carolina – Scottish

- 1685 – Fort Saint Louis (Texas)- French

- 1698 – Pensacola, Florida – Spanish (colonized by Tomas Romero II)

- 1699 – Louisiana (New France) – French;[20]

1700 to 1799

- 1704: Gibraltar captured by British on 4 August; becomes British naval bastion into the 21st century[21]

- 1713: Treaty of Utrecht, ends War of the Spanish Succession and gives Britain territorial gains, especially Gibraltar, Acadia, Newfoundland, and the land surrounding Hudson Bay. The lower Great Lakes-Ohio area became a free trade zone.[22]

- 1756–1763 Seven Years' War, Britain, Prussia, and Hanover against France, Austria, the Russian Empire, Sweden, and Saxony. Major battles in Europe and North America; the East India Company also in involved in the Third Carnatic War (1756–1763) in India. Britain victorious and takes control of all of Canada; France seeks revenge.[23][24]

- 1775–1783: American Revolutionary War as Thirteen Colonies revolt; Britain has no major allies. It is the first successful colonial revolt in European history.[25]

- 1783: Treaty of Paris ends Revolutionary War; British give generous terms to US with boundaries as British North America on north, Mississippi River on west, Florida on south. Britain gives East and West Florida to Spain[26]

- 1784: Britain allows trade with America but forbid some American food exports to West Indies; British exports to America reach £3.7 million, imports only £750,000

- 1784: Pitt's India Act re-organised the British East India Company to minimise corruption; it centralised British rule by increasing the power of the Governor-General

1793 to 1870

- 1792: In India, British victory over Tipu Sultan in Third Anglo-Mysore War; cession of one half of Mysore to the British and their allies.[27]

- 1793–1815: Wars of the French Revolution, and Napoleonic wars; French conquests spread Ideas of the French Revolution, including abolition of serfdom, modern legal systems, and of Holy Roman Empire; stimulate rise of nationalism

- 1804–1865: Russia expand across Siberia to Pacific.[28]

- 1804–1813: Uprising in Serbia against the ruling Ottoman Empire

- 1807: Britain makes the international slave trade criminal; Slave Trade Act 1807; United States criminalizes the international slave trade at the same time.

- 1810–1820s: Spanish American wars of independence[29]

- 1810–1821: Mexican War of Independence[30]

- 1814–15: Congress of Vienna; Reverses French conquests; restores reactionaries to power. However, many liberal reforms persist; Russia emerges as a powerful factor in European affairs.[31]

- 1815–1817: Serbian uprising leading to Serbian autonomy

- 1819: Stamford Raffles founds Singapore as outpost of British Empire.[32]

- 1821–1823: Greek War of Independence

- 1822: Independence of Brazil proclaimed by Dom Pedro I[33]

- 1822–27: George Canning in charge of British foreign policy, avoids co-operation with European powers.[34]

- 1823: United States issues Monroe Doctrine to preserve newly independent Latin American states; issued in cooperation with Britain, whose goal is to prevent French & Spanish influence and allow British merchants access to the opening markets. American goal is to prevent the New World becoming a battlefield among European powers.[35]

- 1821–32: Greece wins Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire; the 1832 Treaty of Constantinople is ratified at the London Conference of 1832.

- 1830: Start of the French conquest of Algeria[36]

- 1833: Slavery Abolition Act 1833 frees slaves in British Empire; the owners (who mostly reside in Britain) are paid £20 million.

- 1839–42: Britain wages First Opium War against China

- 1842: Britain forces China to sign the Treaty of Nanking. It opens trade, cedes territory (especially Hong Kong), fixes Chinese tariffs at a low rate, grants extraterritorial rights to foreigners, and provides both a most favoured nation clause, as well as diplomatic representation.[37]

- 1845: Oregon boundary dispute threatens war between Great Britain and the United States.[38]

- 1846: Oregon Treaty ends dispute with the United States. Border settled on the 49th parallel. The British territory becomes British Columbia and later joins Canada. The American territory becomes Oregon Territory and will later become the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as parts of Wyoming and Montana.[39][40]

- 1846: The Corn Laws are repealed; free trade in grain strengthens the British economy By increasing trade with exporting nations.[41]

- 1845: Republic of Texas voluntarily joins the United States. Annexation causes the Mexican–American War, 1846–48.

- 1848: United States victorious in Mexican–American War; annexes area from New Mexico to California

- 1848–49: Second Sikh war; the British East India Company subjugates the Sikh Empire, and annexes Punjab

- 1857: Indian Rebellion suppressed. It has major long-term impact on reluctance to grant independence to Indians.[42]

- 1858: The government of India transferred from East India Company to the crown; the government appoints a viceroy. He rules portions of India directly, and dominates local princes in the other portions. British rule guarantees that local wars will not happen inside India.[43][44]

- 1861–1867: French intervention in Mexico; United States demands French withdrawal after 1865; France removes its army, and its puppet Emperor is executed.

- 1862: Treaty of Saigon; France occupies three provinces in southern Vietnam.[45]

- 1863: France establishes a protectorate over Cambodia.

- 1867: British North America Act, 1867 creates the Dominion of Canada, a federation with internal self-government; foreign and defence matters are still handled by London.[46]

1870–1914

- 1874: Second Treaty of Saigon, France controls all of South Vietnam

- 1875–1900: Britain, France, Germany, Portugal and Italy join in the Scramble for Africa[47]

- 1876: Korea signs unequal treaty with Japan

- 1878: Austria occupies Bosnia-Herzegovina while Ottoman Empire is at war with Russia

- 1878: Ottoman Empire wins main possessions in Europe; Treaty of Berlin recognising the independence of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro and the autonomy of Bulgaria

- 1882: Korea signs equal treaties with the United States and others

- 1884: France makes Vietnam a country .

- 1885: King Leopold of Belgium establishes the Congo Free State, under his personal control. There is a role for the government of Belgium until the King's financial difficulties lead to a series of loans; it takes over in 1908.[48]

- 1893: France makes Laos a protectorate.[49]

- 1893: Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

- 1895: Creation of French West Africa (AOF)

- 1896–1910: Japan takes full control of Korea.[50]

- 1900: Fashoda Incident in Africa threatens war between France and Britain; Settled peacefully

- 1898: United States demands that Spain immediately reform its rule in Cuba; Spain procrastinates; US wins short Spanish–American War

- 1898: Annexation of the Republic of Hawaii as a United States territory via the Newlands Resolution[51]

- 1898: In the Treaty of Paris, the United States obtains the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and makes Cuba a protectorate.[52]

- 1899–1900: Anti-imperialist sentiment in the United States mobilizes but fails to stop the expansion.[53]

- 1900-08: King Leopold is denounced worldwide for his maltreatment of rubber workers in Congo. The campaign is led by journalist E.D. Morel.[54]

- 1908: Austria annexes Bosnia and Herzegovina; pays compensation and colonial issues. The chief pressure group was the Parti colonial, a coalition of 50 organizations with a combined total of 5,000 members.[55]

1914–1919

- 1917: Jones Act gives full American citizenship to Puerto Ricans.[56]

- 1918: Austrian Empire ends, Austria becomes a republic, Hungary becomes a kingdom, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia become independent

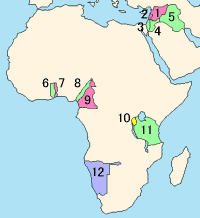

1. Syria, 2. Lebanon, 3. Palestine, 4. Transjordan, 5. Mesopotamia, 6. British Togoland, 7. French Togoland, 8. British Cameroons, 9. French Cameroun, 10. Ruanda-Urundi, 11. Tanganyika and 12. South West Africa

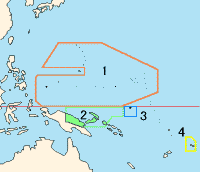

- 1919: German and Ottoman colonies came under the control of the League of Nations, which distributed them as "mandates" to Great Britain, France, Japan, Belgium, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[57]

Maps

See also

- Timeline of European exploration

- Chronology of Western colonialism

- British Empire

- French colonial empire

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- Chinese expansionism

- Empire of Japan

- Inca Empire

- Ottoman Empire

- Timeline of the European colonization of North America

Notes

- ^ Perry J. Moree, A Concise History of Dutch Mauritius, 1598-1710: A Fruitful and Healthy Land (Routledge, 1998).

- ^ Om Prakash, The Dutch East India Company and the Economy of Bengal, 1630-1720 (2014)

- ^ Leonard Blusse, An Insane Administration and Insanitary Town: The Dutch East India Company and Batavia (1619–1799) (Springer Netherlands, 1985).

- ^ Jack S. Levy and Salvatore Ali. "From commercial competition to strategic rivalry to war: The evolution of the Anglo-Dutch rivalry, 1609-52." in Paul Diehl, ed. The dynamics of enduring rivalries (1998) pp29-63.

- ^ Donald C. Wellington, French East India companies: A historical account and record of trade (Hamilton Books, 2006)

- ^ Theodore G. Corbett, "Migration to a Spanish imperial frontier in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: St. Augustine." Hispanic American Historical Review (1974): 414–430 in JSTOR

- ^ Charles W. Arnade, "Cattle Raising in Spanish Florida, 1513–1763." Agricultural History (1961): 116–124. in JSTOR

- ^ Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- ^ Horgan, Paul (1994). The Centuries of Santa Fe. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826314918.

- ^ Addison Emery Verrill, The Bermuda Islands: Their Scenery, Climate, Productions, Physiography, Natural History and Geology: With Sketches of Their Early History and the Changes Due to Man (1902) online

- ^ Wesley Frank Craven, "An introduction to the history of Bermuda." William and Mary College Quarterly (1937): 318–362. in JSTOR

- ^ George F. Dow, Every Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1935).

- ^ Olmert, Michael (2007). Official Guide to Colonial Williamsburg. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. ISBN 9780879352349.

- ^ Liam Connell, "‘A Great or Notorious Liar’: Katherine Harrison and her Neighbours, Wethersfield, Connecticut, 1668–1670." Eras 12.2 (2011); Story of an accused witch put on trial but survived. online

- ^ Arnold, Samuel Greene (1859). History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations vol 1 1636–1700. Applewood Books. ISBN 9781429022774.

- ^ Joseph Dow (1894). History of the Town of Hampton, New Hampshire: From Its Settlement in 1638, to the Autumn of 1892. ISBN 9781548542160.

- ^ Fraser, Walter J. (1990). Charleston! Charleston!: The History of a Southern City. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872497979.

- ^ Illick, Joseph E. (1976). Colonial Pennsylvania: A History. Scribner. ISBN 9780684145655.

- ^ John Francis McDermott, The French in the Mississippi Valley (1965)

- ^ Carl A. Brasseaux, "The Moral Climate of French Colonial Louisiana, 1699–1763." Louisiana History (1986): 27-41. in JSTOR

- ^ Stetson Conn, Gibraltar in British diplomacy in the eighteenth century (1942).

- ^ R. Cole Harris; Geoffrey J. Matthews (1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: From the beginning to 1800. U. of Toronto Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780802024954.

- ^ Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (2001)

- ^ Julia Osman, online essay

- ^ Edward Gray and Jane Kamensky, eds/ The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2013) Wide-ranging overview by scholars.

- ^ Andrew Stockley, Britain and France at the Birth of America: The European Powers and the Peace Negotiations of 1782-1783 (U. of Exeter Press, 2001)

- ^ Denys Mostyn Forrest, Tiger of Mysore: The life and death of Tipu Sultan (1970)

- ^ Mark Bassin, "Inventing Siberia: visions of the Russian East in the early nineteenth century." American Historical Review 96.3 (1991): 763-794. online

- ^ Rory Miller, Britain and Latin America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (1993).

- ^ Barbara A. Tenenbaum, "Merchants, Money, and Mischief the British in Mexico, 1821–1862." The Americas 35.03 (1979): 317-339.

- ^ Brian E. Vick, The Congress of Vienna: power and politics after Napoleon (Harvard UP, 2014).

- ^ Victoria Glendinning, Raffles and the Golden Opportunity (2012).

- ^ Alan K. Manchester, "The recognition of Brazilian independence." Hispanic American Historical Review 31.1 (1951): 80-96 in JSTOR.

- ^ H.W.V. Temperley, The Foreign Policy of Canning, 1822-1827: England, the Neo-Holy Alliance, and the New World (1925) online

- ^ Dexter Perkins, "Europe, Spanish America, and the Monroe Doctrine." American Historical Review (1922) 27#2 pp: 207–218. in JSTOR

- ^ Jennifer E. Sessions (2015). By Sword and Plow: France and the Conquest of Algeria. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801454462.

- ^ James S. Olson and Robert Shadle, eds. Historical dictionary of the British empire (1996) vol 1 p 47

- ^ Joseph Schafer, "The British Attitude toward the Oregon Question, 1815–1846." American Historical Review (1911) 16#2 pp: 273–299. in JSTOR

- ^ Richard W. Van Alstyne, "International Rivalries in Pacific Northwest." Oregon Historical Quarterly (1945): 185–218. in JSTOR

- ^ David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1973).

- ^ Bernard Semmel, The Rise of Free Trade Imperialism: Classical Political Economy the Empire of Free Trade and Imperialism, 1750–1850 (2004)

- ^ Michael Adas, "Twentieth Century Approaches to the Indian Mutiny of 1857–58", Journal of Asian History (1971) 5#1 pp 1–19

- ^ Bhupen Qanungo, "A study of British relations with the native states of India, 1858–62." Journal of Asian Studies (1967) 26#2 pp: 251–265.

- ^ Donovan Williams, "The Council of India and the Relationship between the Home and Supreme Governments, 1858–1870." English Historical Review (1966): 56–73 in JSTOR.

- ^ Oscar Chapuis, The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai (Greenwood, 2000). online

- ^ Donald Creighton, The Road to Confederation: The Emergence of Canada, 1863–1867 (1965).

- ^ Thomas Pakenham, Scramble for Africa: The White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876–1912 (1991)

- ^ Adam Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost (1998)

- ^ Martin Stuart-Fox, "The French in Laos, 1887–1945." Modern Asian Studies (1995) 29#1 pp: 111–139.

- ^ Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895–1910 (1995)

- ^ Thomas J. Osborne, "The Main Reason for Hawaiian Annexation in July, 1898," Oregon Historical Quarterly (1970) 71#2 pp. 161–178 in JSTOR

- ^ Fabian Hilfrich, Debating American Exceptionalism: Empire and Democracy in the Wake of the Spa (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

- ^ Christopher Lasch, "The Anti-Imperialists, the Philippines, and the Inequality of Man." Journal of Southern History (1958): 319–331. in JSTOR

- ^ Matthew G. Stanard, Selling the Congo: A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism (U of Nebraska Press, 2012).

- ^ Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur And Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe, 1914–1940 (1995) p 6

- ^ Willie Santana, "Incorporating the Lonely Star: How Puerto Rico Became Incorporated and Earned a Place in the Sisterhood of States." Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy 9 (2013) pp: 433+ online.

- ^ Nele Matz, "Civilization and the Mandate System under the League of Nations as Origin of Trusteeship." Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law (2005) 9#1 pp: 47–95. online

Further reading

Surveys

- Morris, Richard B. and Graham W. Irwin, eds. Harper Encyclopedia of the Modern World: A Concise Reference History from 1760 to the Present (1970) online

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp; a basic introduction, 1815–1955 online free to borrow

- Baumgart, Winfried. Imperialism: The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion, 1880–1914 (1982)

- Betts, Raymond F. The False Dawn: European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (1975)

- Betts, Raymond F. Uncertain Dimensions: Western Overseas Empires in the Twentieth Century (1985)

- Black, Jeremy. European International Relations, 1648–1815 (2002) excerpt and text search

- Burbank, Jane, and Frederick Cooper. Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference (2011), Very wide-ranging coverage from Rome to the 1980s; 511pp

- Dodge, Ernest S. Islands and Empires: Western Impact on the Pacific and East Asia (1976)

- Furber, Holden. Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, 1600-1800 (1976)

- Furber, Holden, and Boyd C Shafer. Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, 1600-1800 (1976)

- Hodge, Carl Cavanagh, ed. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914 (2 vol. 2007), Focus on European leaders

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (1989) excerpt and text search; very wide-ranging, with much on economic power

- Langer, William. An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed. 1973), very detailed outline; 6th edition ed. by Peter Stearns (2001) has more detail on Third World

- McAlister, Lyle N. Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492-1700 (1984)

- Mowat, R. B. A History of European Diplomacy 1815–1914 (1922), basic introduction

- Page, Melvin E. ed. Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia (3 vol. 2003); vol. 3 consists of primary documents; vol. 2 pages 647-831 has a detailed chronology

- Porter, Andrew. European Imperialism, 1860-1914 (1996), Brief survey focuses on historiography

- Savelle, Max. Empires to Nations: Expansion in America, 1713-1824 (1975)

- Smith, Tony. The Pattern of Imperialism: The United States, Great Britain and the Late-Industrializing World Since 1815 (1981)

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) excerpt and text search; advanced analysis Of diplomacy

- Wilson, Henry. The Imperial Experience in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1870 (1977)

Africa

- Pakenham, Thomas (1991). The Scramble for Africa, 1876–1912. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-51576-5..

- Wesseling, H.L. and Arnold J. Pomerans. Divide and rule: The partition of Africa, 1880–1914 (Praeger, 1996.) online

Asia

- Cady, John Frank. The roots of French imperialism in Eastern Asia (1967).

- Darby, Phillip. Three Faces of Imperialism: British and American Approaches to Asia and Africa, 1870-1970 (1987)

- Davis, Clarence B. "Financing Imperialism: British and American Bankers as Vectors of Imperial Expansion in China, 1908–1920." Business History Review 56.02 (1982): 236–264.

- Harris, Paul W. "Cultural imperialism and American protestant missionaries: collaboration and dependency in mid-nineteenth-century China." Pacific Historical Review (1991): 309–338. in JSTOR

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz. Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864-1914: A Study in Imperialism (1968)

- Lebra-Chapman, Joyce. Japan's Greater East Asia co-prosperity sphere in World War II: selected readings and documents (Oxford University Press, 1975)

- Lee, Robert. France and the exploitation of China, 1885-1901: A study in economic imperialism (1989)

- Webster, Anthony. Gentleman Capitalists: British Imperialism in Southeast Asia 1770-1890 (IB Tauris, 1998)

Atlantic world

- Greene, Jack P., and Philip D. Morgan, Atlantic History: A Critical Appraisal, ed. by (Oxford University Press, 2009)

- Hodson, Christopher, and Brett Rushforth, "Absolutely Atlantic: Colonialism and the Early Modern French State in Recent Historiography," History Compass, (January 2010) 8#1 pp 101–117

Latin America

- Brown, Matthew, ed. Informal Empire in Latin America: Culture, Commerce, and Capital (2009)

- Dávila, Carlos, et al. . Business History in Latin America: The Experience of Seven Countries (Liverpool University Press, 1999) online

- Miller, Rory. Britain and Latin America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Longman, 1993)

British Empire

- Bayly, C. A. ed. Atlas of the British Empire (1989). survey by scholars; heavily illustrated

- Brendon, Piers. "A Moral Audit of the British Empire." History Today, (Oct 2007), Vol. 57 Issue 10, pp 44–47, online

- Brendon, Piers. The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781-1997 (2008), wide-ranging survey

- Colley, Linda. Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600-1850 (2004), 464pp

- Dalziel, Nigel. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire (2006), 144 pp

- Darwin, John. The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830-1970 (2009) excerpt and text search

- Darwin, John. Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain (2013)

- Ferguson, Niall. Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (2002)

- Gallagher, John, and Ronald Robinson. "The Imperialism of Free Trade" Economic History Review (1953) 6#1 pp: 1-15. Highly influential argument that British merchants and financiers imposed an economic imperialism without political control. in JSTOR

- Hyam, Ronald. Britain's Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion (1993).

- James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997), very highly regarded survey.

- Judd, Denis. Empire: The British Imperial Experience, From 1765 to the Present (1996). online edition

- Lloyd; T. O. The British Empire, 1558-1995 Oxford University Press, 1996 online edition

- Louis, William. Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire, 5 vols. (1998–99).

- vol 1 "The Origins of Empire" ed. by Nicholas Canny

- vol 2 "The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall excerpt and text search

- vol 3 The Nineteenth Century edited by William Roger Louis, Alaine M. Low, Andrew Porter; (1998). 780 pgs. online edition

- vol 4 The Twentieth Century edited by Judith M. Brown, (1998). 773 pgs online edition

- vol 5 "Historiography" ed, by Robin W. Winks (1999)

- Marshall, P.J. (ed.) The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996). excerpt and text search

- James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997).

- Marshall, P.J. (ed.) The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996). excerpt and text search

- Robinson, Howard. The Development of the British Empire (1922), 465pp 30 online edition

- Schreuder, Deryck, and Stuart Ward, eds. Australia's Empire (Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series) (2010)

- Simms, Brendan. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire (2008), 800pp excerpt and text search

- Smith, Simon C. British Imperialism 1750-1970 (1998). brief

- Stockwell, Sarah, ed. The British Empire: Themes and Perspectives (2008) 355pp.

- Weigall, David. Britain and the World, 1815–1986: A Dictionary of International relations (1989)

French Empire

- Hutton, Patrick H. ed. Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940 (2 vol 1986)

- Northcutt, Wayne, ed. Historical Dictionary of the French Fourth and Fifth Republics, 1946- 1991 (1992)

- Aldrich, Robert. Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion (1996)

- Betts, Raymond. Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914 (2005) excerpt and text search

- Clayton, Anthony. The Wars of French Decolonization (1995)

- Newbury, C. W.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1969). "French Policy and the Origins of the Scramble for West Africa". The Journal of African History. 10 (2): 253–276. doi:10.1017/s0021853700009518. S2CID 162656377..

- Roberts, Stephen H. History of French Colonial Policy (1870-1925) (2 vol 1929) vol 1 online also vol 2 online; Comprehensive scholarly history

- Rosenblum, Mort. Mission to Civilize: The French Way (1986) online review

- Priestley, Herbert Ingram. (1938) France overseas;: A study of modern imperialism 463pp; encyclopedic coverage as of late 1930s

- Thomas, Martin. The French Empire Between the Wars: Imperialism, Politics and Society (2007) 1919–1939

- Thompson, Virginia, and Richard Adloff. French West Africa (Stanford University Press, 1958)

Decolonization

- Lawrence, Adria K. Imperial Rule and the Politics of Nationalism: Anti-Colonial Protest in the French Empire (Cambridge UP, 2013) online reviews

- Rothermund, Dietmar. Memories of Post-Imperial Nations: The Aftermath of Decolonization, 1945-2013 (2015) excerpt; Compares the impact on Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Portugal, Italy and Japan

- Sanders, David. Losing an Empire, Finding a Role: British Foreign Policy Since 1945 (1990) broad coverage of all topics in British foreign policy

- Simpson, Alfred William Brian. Human Rights and the End of Empire: Britain and the Genesis of the European Convention (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Smith, Tony. "A comparative study of French and British decolonization." Comparative Studies in Society and History (1978) 20#1 pp: 70-102. online

- Thomas, Martin, Bob Moore, and Lawrence J. Butler. Crises of Empire: Decolonization and Europe's imperial states (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015)

Primary sources

- Page, Melvin E. ed. Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia (3 vol. 2003); vol. 3 consists of primary documents