| 145th Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 3 April 1999 | ||

| Winner | Cambridge | ||

| Margin of victory | 3+1⁄2 lengths | ||

| Winning time | 16 minutes 41 seconds | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 76–68 | ||

| Umpire | Mark Evans (Oxford) | ||

| Other races | |||

| Reserve winner | Goldie | ||

| Women's winner | Cambridge | ||

| |||

The 145th Boat Race took place on 3 April 1999. Held annually, the Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge along the River Thames. Featuring the tallest rower in Boat Race history at that time, Cambridge won the race in the second-fastest time ever. It was their seventh consecutive victory in the event.

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie defeated Oxford's Isis in the fastest time ever, while Cambridge won the Women's Boat Race.

Background

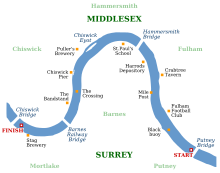

The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the University of Oxford (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues")[1] and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Light Blues").[1] First held in 1829, the race takes place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[2] The rivalry is a major point of honour between the two universities and followed throughout the United Kingdom and broadcast worldwide.[3][4] Cambridge went into the race as reigning champions, having won the 1998 race by three lengths,[5] with Cambridge leading overall with 75 victories to Oxford's 68 (excluding the "dead heat" of 1877).[6]

The first Women's Boat Race took place in 1927, but did not become an annual fixture until the 1960s. Up until 2014, the contest was conducted as part of the Henley Boat Races, but as of the 2015 race, it is held on the River Thames, on the same day as the men's main and reserve races.[7] The reserve race, contested between Oxford's Isis boat and Cambridge's Goldie boat has been held since 1965. It usually takes place on the Tideway, prior to the main Boat Race.[5]

Andrew Lindsay was confident that the Oxford crew would be more motivated than their opponents: "our advantage over Cambridge is that we are hungry for the victory. Everyone in the Oxford boat is driven to go and win this damn thing".[8] He was making his third and final appearance in the race having lost in both the 1997 and 1998 race. His grandfather represented Cambridge in the 1930s, and his uncle, Alexander Lindsay, rowed for the losing Oxford crew in the 1959 race before triumphing the following year.[8] Cambridge boat club president and Canadian international rower Brad Crombie was also making his third Boat Race appearance, attempting to complete a hat-trick of victories.[8] Sean Bowden was the head coach of Oxford. His Cambridge counterpart, Robin Williams, suggested "it still feels like all or nothing to us. The fear of defeat, the aim of trying to push the limits is motivation itself".[8] Just as he had done in the 1993 race, umpire Mark Evans introduced modifications to the starting procedure, suggesting that he would be content to hold the crews for up to ten seconds between issuing the "set" and "go" commands.[9] Cambridge's Williams remarked: "I'm happy as long as both crews abide by it", Bowden was nonplussed "Go is when you start races. I'm happy."[9]

The race was sponsored for the first time by Aberdeen Asset Management,[10] and both crews were competing for the Aberdeen Asset Trophy. It was the fiftieth anniversary of the BBC's coverage of the event and over the preceding five years had secured an average audience in excess of six million.[11]

Crews

The Oxford crew weighed-in at an average of 14 st 10 lb (93.2 kg), 0.5 pounds (0.23 kg) more per rower than Cambridge.[12] Josh West, rowing at number four for Cambridge, became the tallest rower in Boat Race history at 6 ft 9 in (2.06 m).[12] The Oxford crew comprised three Britons, three Americans, a Swede, a Canadian and a German, while Cambridge were represented by five Britons, two Americans, a German and a Canadian.[12] Three former Blues returned for Cambridge in Wallace, Crombie and Smith, while Oxford saw Humphreys and Lindsay return.[12] Vian Sharif, the Cambridge cox, became the tenth female to steer a Boat Race crew, and was the lightest competitor at the event since the 1986 race.[12]

| Seat | Oxford |

Cambridge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Nationality | College | Weight | Name | Nationality | College | Weight | |

| Bow | Charlie P A Humphreys (P) | British | Oriel | 13 st 1.5 lb | Toby J Wallace | British | Jesus | 15 st 2 lb |

| 2 | Henrik K Nilsson | Swedish | Hertford | 14 st 2 lb | T A Stallard | British | Jesus | 13 st 8.5 lb |

| 3 | D R Snow | British | Balliol | 15 st 12 lb | Brad Crombie (P) | Canadian | Peterhouse | 14 st 12 lb |

| 4 | Toby H Ayer | American | Worcester | 16 st 0 lb | A J West | American | Gonville and Caius | 15 st 2.5 lb |

| 5 | Martin Crotty | American | Keble | 14 st 10 lb | David O M Ellis | American | Trinity | 14 st 4 lb |

| 6 | Morgan A L Crooks | Canadian | Keble | 14 st 4 lb | K M West | British | Christ's | 14 st 13 lb |

| 7 | A J R Lindsay | British | Brasenose | 14 st 4 lb | Graham D C R Smith | British | St Edmund's | 14 st 2.5 lb |

| Stroke | Colin von Ettingshausen | German | Keble | 15 st 2 lb | Tim Wooge | German | Magdalene | 15 st 2 lb |

| Cox | Neil J O'Donnell | American | Keble | 7 st 13 lb | Vian Sharif | British | Clare | 6 st 10.5 lb |

| Source:[13] (P) – boat club president | ||||||||

Race

Bookmakers could not initially separate the crews, offering odds on for either boat to win.[12] However, as the start of the race approached, Williams had suggested that he was worried by his crew's "inconsistency" and Oxford were declared favourites.[14] Cambridge won the toss and elected to start from the Surrey station. Despite being warned by the umpire, Cambridge were soon half-a-length ahead, and a second clear by the Mile Post.[14] The lead was extended to a length by Hammersmith Bridge and Sharif had steered her boat into a better angle of attack. Pushing on, Cambridge were seven seconds up by Chiswick Steps and nine seconds at Barnes Railway Bridge. They passed the finishing post 3+1⁄2 lengths ahead, with an eleven-second advantage over the Dark Blues. The Light Blues finished in 16 minutes 41 seconds, a time only bettered once before, in 1998.[5][14] It was the first time since 1936 that Cambridge had secured seven consecutive victories.[14]

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie beat Oxford's Isis by 1+1⁄2 lengths, their ninth victory in ten years, and in a record time of 16 minutes 58 seconds which beat the fastest time recorded in 1996 and repeated in 1998.[5] Cambridge won the 51st Women's Boat Race by one length in a time of 6 minutes 1 second, their eighth consecutive victory.[5]

Reaction

Oxford's Bowden was dumbstruck: "I'm really floored. I just haven't got any answers until I talk to the crew."[15] His number four, Toby Ayer admitted: "my impression is that they were quicker than us and that is a very hard thing to have to say."[15] Cambridge's Williams noted: "I thought it would be a bit more competitive than that."[15] Cambridge boat club president Crombie exclaimed "that's the most fun I've ever had rowing for Cambridge."[15]

References

- ^ a b "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Former Winnipegger in winning Oxford–Cambridge Boat Race crew". CBC News. 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "TV and radio". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Boat Race – Results". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Classic moments – the 1877 dead heat". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "A brief history of the Women's Boat Race". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Rob (31 March 1999). "Hunger the starter in university challenge". The Times. No. 66475. p. 42.

- ^ a b Rosewell, Mike (2 April 1999). "Oxford are starting to impress". The Times. No. 66477. p. 52.

- ^ Matheson, Hugh (26 January 1999). "Rowing: New sponsor keeps Boat Race afloat". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Rosewell, Mike; Goodbody, John (3 April 1999). "Oxford prepare to pay back old rivals for past defeats". The Times. No. 66478. p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Roswell, Mike (25 March 1997). "Weigh-in offers few clues to the outcome of Boat Race". The Times. No. 65846. p. 48.

- ^ Rosewell, Mike (30 March 1999). "History weighs heavily on Oxford". The Times. No. 66474. p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Rosewell, Mike (5 April 1999). "Oxford fail to live up to expectations". The Times. No. 66478. p. 32.

- ^ a b c d Longmore, Andrew (4 April 1999). "The 145th Boat Race: Classic Cambridge turn the screw". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.