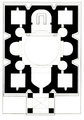

A tetraconch, from the Greek for "four shells", is a building, usually a church or other religious building, with four apses, one in each direction, usually of equal size. The basic ground plan of the building is therefore a Greek cross. They are most common in Byzantine, and related schools such as Armenian and Georgian architecture. It has been argued that they were developed in these areas or Syria, and the issue is a matter of contention between the two nations in the Caucasus.[1] Apart from churches, the form is suitable for a mausoleum or baptistery. Normally, there will be a higher central dome over the central space.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/1Views:780

-

A World Monument: Zvart'nots', Armenia, & the Wars of the Seventh Century

Transcription

Overview

The Basilica of San Lorenzo, Milan (370) is possibly the first example of a grander type, the "aisled tetraconch", with an outer ambulatory. In middle Byzantine architecture, the cross-in-square plan was developed, essentially filling out the tetraconch to form a square-ish exterior. Either of these types may also be described less precisely as "cross-domed". In these types the semi-dome of the apse usually starts directly from the central domed space.

The ruined Ninotsminda Cathedral of c.575 in Georgia is perhaps the oldest example in that country. The Armenian and Georgian examples are later than some others but a distinctive and sophisticated form of the plan. They are similar to the cross-in-square plan, but in Georgia the corner spaces, or "angle chambers", are only accessible from the central space through narrow openings, and are closed off from the apses (as at Jvari monastery, see plan above). In Armenia, the plan also developed in the 6th century, where the plan of St. Hripsime Church, Echmiadzin (618) is almost identical to Jvari.[2] Later a different plan was developed, with a tetraconch main space completely encircled by an aisle, or ambulatory in the terminology used for Western churches,[3] as at the ruined mid-7th century Zvartnots Cathedral.[4] The ruined so-called Cathedral of Bosra, of the early 6th century, is the earliest major Syrian tetraconch church,[5] though in Syria the type did not remain as popular as in the Caucasus.

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna (425–30), world-famous for its mosaics, is almost a tetraconch, although there are short vaulted arms leading from the central space to each apse-end. These end in a flat wall with no semi-dome, and the entrance end is slightly longer.

A famous revival of the tetraconch formula in the West is Bramante's first design for the Basilica of St. Peter, Rome.

-

Plan of Saint Hripsime Church, Armenia, 7th-century

-

Bramante's plan for St Peter's Basilica, 1503–06

-

Floorplan of Saint Sava, Belgrade, 2004

Triconch

A triconch building has only three apses; normally omitting the one at the liturgical west end, which may be replaced with a narthex. The eastern apse may be considerably larger than the ones to north and south. Many churches of both types have been extended, especially to the west by addition of naves, so that they came to resemble more conventional basilica-type churches. The church in Istanbul of St. Mary of the Mongols is an example. Many triconch churches were built with a nave from the start; this formula was very common in the West, especially in Romanesque architecture.

Notes

References

- V.I. Atroshenko and Judith Collins, The Origins of the Romanesque, Lund Humphries, London, 1985, ISBN 0-85331-487-X

- Hill, Julie. The Silk Road Revisited: Markets, Merchants and Minarets, AuthorHouse, 2006, ISBN 1-4259-7280-2, Google books

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene. Zvart'nots and the Origins of Christian Architecture in Armenia, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 245–262 JSTOR

External links

- Graphic model of a 7th-century Armenian simple tetraconch church.