| Suntop Homes | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | Usonian |

| Location | Ardmore, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40°00′00″N 75°17′32″W / 39.999917°N 75.292183°W |

| Construction started | 1939 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Frank Lloyd Wright |

The Suntop Homes, also known under the early name of The Ardmore Experiment, were quadruple residences located in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, and based largely upon the 1935 conceptual Broadacre City model of the minimum houses. The design was commissioned by Otto Tod Mallery of the Tod Company in 1938 in an attempt to set a new standard for the entry-level housing market in the United States and to increase single-family dwelling density in the suburbs. In cooperation with Frank Lloyd Wright, the Tod Company secured a patent[1] for the unique design, intending to sell development rights for Suntops across the country.

The first (and only) of the four buildings planned for Ardmore was built in 1939, with the involvement of Wright's master builder Harold Turner, after initial construction estimates far surpassed the project budget set by the Tod Company. There were several reasons that construction of the other three planned units did not move forward, including the escalation of the World War, high construction costs and later, protests by local residents against multi-family housing in the neighborhood.

Fire damaged or destroyed two of the four original dwellings. The first was badly damaged only a few years after construction was completed, and remained as a burned-out shell for several decades before it was restored by a private owner using Wright's original plans and early concepts. A second residence was lost to fire in the 1970s during an interior restoration, but was rebuilt with extensive changes to the plan and ceiling heights. The carports of several residences have been enclosed to provide more interior space.

Later projects modeled on the quadruple dwelling unit included the Cloverleaf Quadruple Housing project (1941/42) for the U.S. Government on a tract near Pittsfield, Massachusetts. A change in housing administration and complaints from local architects that they, not an "outsider," should design the project, prevented construction.

Floorplan and features

The Ardmore Experiment was designed so each building had four individual Usonian dwellings around a central point, in a radial pinwheel plan. The living spaces of each unit were stacked vertically instead of horizontally. This is a departure, because horizontal arrangement was typical of Wright's residential work at the time. However, most of this work was for wealthy families. A single floor is more comfortable, but more expensive in land.

The arrangement combined the usual suburban front and rear yards into single outdoor spaces or gardens. In planning the initial Tod Company development, Wright arranged four buildings (16 dwellings) asymmetrically on the lot so that no unit's view directly faced another (or any existing neighbor). This maximized privacy and shared green space at the same time.[2]

The prototype Suntop building has four separate quadrants. Each quadrant is an individual dwelling designed for 2,300 square feet (210 m2), stacked in four floors. The dwellings are separated by fireproof, soundproof brick walls. The walls cut off all sight lines from any part of any dwelling to any part of the other dwellings in the building. The floor-plans reduce the effects of noise by placing a dwelling's daytime activities (e.g. kitchen, bath, etc.) on one side of each wall, and the adjacent dwelling's night time activities (bedrooms, etc.) on the other side of the same wall. The walls also contain all vents to the roof, including the heater and fireplace chimneys. The barrier walls go below grade, dividing a single, small, economical central excavation into four small basement heater rooms.[2]

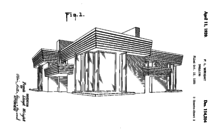

A walk-through logically starts outside the combined driveway and entrance walkway, which lead to the carport. (In the patent drawing, the carport opening is below the narrower, second-story parapet.) From the entrance, the planked parapets of the balcony and terrace help privacy by cutting off sight-lines to the windows of the master bedroom and penthouse bedrooms on the roof terrace. (This is why those windows are not visible in the patent drawing.) The planked parapets shade the garden and walk. The parapets also make each unit's balcony and terrace safe even for small children. They also reinforce each other visually. In some drawings, planters line the parapets, with greenery spilling down them. Owners liked the parapet design well-enough to adopt it for garden walls.[3][2]

The balcony shelters the carport's entranceway and its pedestrian entrance on the inside right. The door in the carport provides access to the street, the carport and basement with one door. Combining the sidewalk and driveway permits more garden space, and also reduces land and construction costs.

Inside the carport, the left wall is the left barrier wall. In the carport's back are some cabinets and the two-flight stair to the basement. It leads to a small below-grade furnace room under the rear floor of the carport. Wright considered basements "waste" so this is an interesting variation from other Usonian houses. It may be an attempt to maximize the convenient living space by placing utilities out of the way.[2]

Utilities are literally centralised for all four units, reducing piping. The floorplan could utilize only electric, oil or gas heat: No coal chute or bin is shown. However, coal heat was common at the time. With minor design changes, including a fuel bin and chute, the heater below the carport permits a vendor to deliver solid fuels by gravity. The basement heater room is below habitable areas, separated from them by masonry walls and two floors, reducing fire risks. The basement is also suitable for a storm shelter. Its walls are bearing walls, it is below grade, and the stair leading to it opens to a barrier wall, protecting the basement entrance from wind-borne projectiles.[2]

Like most Usonian houses, Suntop utilizes radiant hydronic heating in the first-floor slab, with radiators in upper rooms. Gravity convection efficiently circulates heated water to the living areas. In each dwelling, the heater room and its water-heater is also directly under the second floor bathroom, and near the second floor kitchen. This can enable instant-on hot water, at some cost in fuel to keep return hot-water loops warm. Wright even designed custom cedar radiator covers for Suntop.[3][2]

Returning to the carport, the main pedestrian entrance is sheltered just inside the right side of the ground-floor carport. Passing in, on the left the three habitation levels are joined by a single four-flight staircase. It connects the main pedestrian entrance on the first floor, the second floor's mezzanine, kitchen, bath and bedrooms and the third floor's bedrooms, and roof terrace. The upper levels wrap around the stairs. The stairs separate private spaces.[3][2]

The pedestrian entrance leads directly to the outside rim of the first-floor's large living room. The entrance faces the dramatic two-story-tall corner window. It dramatically brings the garden inside. The walls of the living room are lined with built-in cedar closets, a fireplace, padded seating, book-shelves and a table.[3]

The window has a corner niche on its outside. In some drawings, a small vertical tree (an Italian cypress or small Lombardy poplar) is in a planter there, and seems inside the room.

The living room can be finished with small sectional sofas or chairs to make conversational niches around the fireplace, window corner and, in the corner opposite the entrance, the library corner and its table. These naturally form social spaces for entertainment and family.

Two-story walk-through ventilation windows open to the garden at the sides of the large corner window. These windows open between the conversational areas and both of them open opposite to the kitchen on the mezzanine.[2]

The library corner is in the quiet corner opposite the entrance. Its built-in table or desk is next to the corner window, with a built-in sofa under the bookshelves and room for chairs on two sides of the table. Modern owners extended the built-in sofa for the entire wall, from the library corner to the fireplace under the mezzanine.

Wright's trademark Usonian fireplace is two-sided, a square on the inside corner of the first-floor living room. The fireplace's brick matches the exposed brick of the barrier wall and the adjacent bearing wall (the rear of the carport is behind it). The fireplace economically uses the corner masonry for its chimney. Since the chimney is mostly in heated areas, the chimney will remain warm, and draw in winter without a backdraft. In the upper stories, the chimney and other ventilation ducts (including the furnace, water-heater, room vents, kitchen and bathroom drain vents) are built into the barrier wall.[2]

Passing by the cedar closets, back to the house entrance, a short two-flight staircase goes up to the second floor. The lower flight's staircase is over the basement stairs, which open to the carport. The upper flight's staircase space is used and concealed by cedar closets facing the living room. The stairs go to the mezzanine's dining loft. Against the second-story's barrier wall (to the right of the patent drawing), a galley kitchen faces the dining area in the mezzanine,

A portion of the mezzanine's ceiling is contiguous with the living room ceiling, but half of the mezzanine has a ceiling a couple of feet (2/3m) higher. This clerestory line joins to the upward stairwell. Clerestory windows in this gap light and ventilate the kitchen's work area, bedroom hall opening, central mezzanine, and the stairwell upward. The clerestory windows open onto the roof terrace. Wright hoped that when the windows were open, a mother working in the kitchen might be able to supervise children on the roof terrace, and vice versa if the mother were on the terrace.

The crowded mezzanine excuses its tight spaces with a cozy nautical flavor: This is from a combination of the galley kitchen, exposed, finished joinery, overhead clerestory, planked ceiling, wood paneling, and built-in dining table. Some owners noticed this and emphasized it with their decor.[3]

The mezzanine opens down to the living room and its dramatic windows. A dining booth is built into the outside corner of the mezzanine, overlooking the corner window of the living room and its entrance-way. The booth's inward-facing seat is the inner side of the mezzanine's parapet. In Wright's drawings, the outer face of the mezzanine's parapet has planters with greenery visible from the outer living room. These would freshen the air, and green complements the red and brown of Wright's materials. Plants here would even be visible outside, through the large windows, and would unify the garden outside with the garden inside.[2]

A decorative, Art Deco Usonian lamp lights the mezzanine's dining-table. It's near the outer corner of the mezzanine, at the level of the living-room ceiling. It lights the mezzanine and kitchen much as the clerestories would. It can serve as a nightlight for the mezzanine, its kitchen, the second story hall, the first-floor's living room entranceway and the outer living room. From the outside, it is clearly visible for long distances through both sides of the two-story living-room window, to welcome guests and family. Its light can't reach or disturb any of the four bedrooms.[2] (Inhabitants have related humorous stories about the difficulty of changing its light-bulbs.)

The inner wall of the mezzanine opens to a hall. Turning right leads first to a linen closet, then past a corner to the left, to help preserve privacy, the hall reaches an enclosed commode and bathroom.

To the left from the mezzanine, behind the stairwell's wall, a short hall leads to the nursery and the master bedroom. The second-floor nursery is to the inside of the master bedroom. Placing the nursery next to the master bedroom permits parents easy access at night. When entering the master bedroom, one faces the outside windows and door to the second-floor parapet over the carport. To the right are built-in twin beds, and shelves or dressers. A changing-table or desk is to the left. Further left, beyond the changing table is the door to a walk-in closet. The closet is over the stairs. The master bedroom and nursery are over the carport, aiding privacy. The master bedroom and closet also have outside windows. Furniture can be lifted from the outside driveway to the parapet and into the bedroom.[2]

Lighting and ventilating the inner rooms of the second floor (nursery, bath and commode) may have challenged Wright, because they don't adjoin exterior walls or the roof. A 6-foot-square (approx. 2m-square) central light well reaches from the roof skylight through the third floor to light and ventilate the bath. The nursery's wall with the master bedroom aligns with the upper penthouse wall, and has clerestory windows high on the walls, facing the roof terrace. The nursery therefore has a ceiling two feet (80cm) higher than the master bedroom. Inhabitants report that the commode, closets and other parts of the inner rooms are also lit and ventilated by clerestories to the light well or roof terrace, concealed in built-in joinery.[3][2]

The second-story master bedroom is designed for privacy. It has no shared floors or walls with spaces that are inhabited at the same time. It's around a corner and down a short hall from the dining mezzanine. Closets separate it from the nursery. The staircase and walk-in wardrobe separate it from the dining mezzanine and upper living room. It's on the "night" side of the barrier wall, opposite the empty wall over the library corner of the adjacent unit. It's over the carport, and below the roof terrace. It has a window and door to the small balcony over the carport and entrance, but the parapet stops sight lines from the yard and driveway.[2]

On the third "penthouse" story, the L-shaped outside terrace wraps around the penthouse. Wright's drawings show clothes-lines and drying clothes on the terrace, sunlit, yet protected from tampering. The planked parapet of the terrace prevents views from the garden or driveway to the terrace, clotheslines, penthouse or clerestory windows. Some drawings show plants hanging from the parapet. The terrace is also the roof of the living room.

The upper flights of stairs lead up from the internal mezzanine on the second floor to a tiny hall on the outer corner of the penthouse. The stairwell is lit by clerestory windows to the terrace, and large windows in the corner of the penthouse hall. The hall windows survey the roof terrace. The hall leads right to the two bedrooms and the terrace door.

The larger bedroom, for guests or older children, is over the kitchen, against the right barrier wall. The smaller bedroom, suitable for young children, is over the nursery. The bedrooms' plans show large windows facing the terrace with closets, built-in twin or bunk beds, night-stands and shelves. The closets adjoin the second-floor bathroom's lightwell, permitting natural light in the closets and on two sides of the bedrooms. The windows of the bedrooms are on different sides of the penthouse, making them private from each other.[2]

The third-story roof terrace's outside door opens from the penthouse hall to a two-foot (60 cm) stair descending to the outside terrace. At the base of the penthouse, this elevation contains clerestory windows from the third-story terrace to the internal second-story nursery, stairwell and central mezzanine.[2]

Criticism

Two dwellings (half of all that were ever built) have burned. The design fails modern fire safety regulations. Drawings show only a door in the back of the carport to keep a car's heavy fuel vapors away from open flames in the below-grade furnace room. Fires apparently stopped after the carports were converted to living space. The design might economically address fire safety by eliminating the basement, saving excavation costs. Modern appliances would fit on a rear shelf in the carport. A simple storm cellar could be optional. Sprinklers are also inexpensive, offset by reduced fire insurance.

Construction was expensive because of Wright's obsession with high-finish joinery.[3] Wright's luxury materials, cantilevers and clerestories are also inherently costly. Textured cement is a Wright material. Textured tilt-up concrete barrier walls might be possible, with some loss of amenities. 3D-printed masonry on a steel frame might economically build almost all amenities, including cantilevers, clerestories, built-in furniture and parapets. Printed built-ins could utilize catalog fittings and upholstery.

The floor plan was for commodity housing. Modern owners complained about the small size of the house and the small bedrooms. Some owners converted the carports to living space. One converted it from a four bedroom house (in plan) to two bedrooms, and added a bath.[3] Many modern owners would expect a commode or bath on each floor, possibly even for each bedroom.[2]

The second and third floor's dining area, kitchen and bedrooms can be uncomfortable for older adults to reach. (To be fair, it was designed for young families.) Groceries had to be carried upstairs. A dumbwaiter, laundry and garbage chutes would help. The needed space might be had by using circular stairs. A redesign for older adults might "unscrew" the floors, putting one apartment on each floor, rotated for privacy, reclaiming the stairwell-area for bathrooms or bedrooms, yet using the same land. This loses much privacy, natural light and the dramatic twelve-foot ceiling of the great room.[2]

Wright's trademark flat roof leaked. The problem was not completely fixed until modern roofing materials solved the issue, at some expense.[3] A low-density reinforced concrete roof with a few percent of rise and a wax or asphalt infusion could hip the roof, balcony and terrace, reducing leaks, yet leave the terrace usable. The insulation (e.g. by pumice aggregate) of the low-density concrete would reduce condensation on rafters (i.e. dry rot), ice-dams on the roof (leaks), and cooling problems that are normally reduced by a vented attic.[4] The outside design would appear unchanged: The parapet could conceal the slight hip and thicker roof. (Wright designed flat roofs to avoid the "waste" of attics.)

Wright expressed concern about ventilation in this design, because each dwelling only has two open sides. A modern design might utilize zoned air circulation, with a heater, whole-house fan and air-conditioning. The patent drawing shows two-story ventilation windows edging the corner window, but modern photos show single-story glass garden doors on the first floor, with screened, tilt-in upper windows. The mezzanine's clerestories should exhaust hot air too, but they are in the wind-shadows of the barrier walls, preventing both breezes and Bernoulli suction. They are small, preventing convection, and their mechanism is high and may be hard to reach. A breeze across the chimney should draw air into the fireplace, but the damper might too often be closed. Also the chimney may reach only the top of the barrier wall, and it may be too short to reach the fast outside air needed for the Bernoulli effect.[2]

Double-insulating the dramatic windows and glass doors would reduce heating and cooling costs. Correct solar design of the terrace's shade line on the windows would keep the sun out in the summer, yet permit solar heat in the winter. North-facing units might be solar-heated with mirrors on the garden fence. A solar roof on the penthouse could reduce the cost of electricity for air-conditioning or a heat pump.

A hinge and latch could make it easy to change the Usonian lamp's light bulbs.

References

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd. "U.S. Design Patent 114,204". U.S. Patent Office. U.S.Government. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "The Ardmore Experiment". The Architectural Forum. January 1938.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Walsh, Thomas J. "Frank Lloyd Wright House for Sale". Patch. Patch.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Alexander, Christopher (1977). A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press.

- Storrer, William Allin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University Of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2 (S.248)

- Sergeant, John. Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses. Whitney Library of Design, 1976, ISBN 0-8230-7177-4

- Wright, Frank Lloyd. The Natural House. Horizon Press, 1954.

External links

- Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record

- Frank Lloyd Wright house | Patent Room

- Suntop Homes

- Suntop Home, Built by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ardmore - Photograph

- Lower Merion Conservancy - Suntop