| St. Jean Baptiste Roman Catholic Church | |

|---|---|

north profile and west elevation; in the background left is The Siena, built using air rights bought from the church (2014) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church (Latin Church) |

| District | Archdiocese of New York |

| Leadership | The Rev. John Kamas, S.S.S. |

| Year consecrated | 1912 |

| Location | |

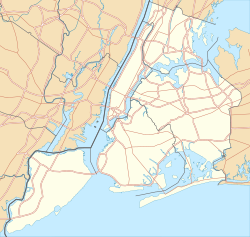

| Location | 1067-71 Lexington Avenue (184 East 76th Street) Manhattan, New York City |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Nicholas Serracino |

| Style | Italian Renaissance Revival, Classical Revival, Italian Mannerism |

| Groundbreaking | 1910 |

| Completed | 1913 |

| Construction cost | $600,000 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | west |

| Capacity | 1,200 |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Dome height (outer) | 175 feet (53 m) |

| Spire(s) | 2 |

| Spire height | 150 feet (46 m) |

| Materials | Limestone |

St. Jean Baptiste Roman Catholic Church | |

| Coordinates | 40°46′21″N 73°57′36″W / 40.77250°N 73.96000°W |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002720 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 23, 1980[2] |

| Designated NYCL | November 19, 1969[1] |

| Website | |

| The Church of St. Jean Baptiste, New York City | |

St. Jean Baptiste Roman Catholic Church, also known as the Église St-Jean-Baptiste, is a Catholic parish church in the Archdiocese of New York at the corner of Lexington Avenue and East 76th Street in the Lenox Hill neighborhood of the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City. The parish was established in 1882 to serve the area's French Canadian immigrant population and remained the French-Canadian National Parish until 1957. It has been staffed by the Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament since 1900.[3]

Financier Thomas Fortune Ryan, a Catholic convert in his teens, bankrolled its construction. It was designed by Nicholas Serracino, an Italian architect practicing in New York, who, inspired by the Italian Mannerists,[4] combined elements of the Italian Renaissance Revival and Classical Revival architectural styles, Seracino won first prize for the design at the Esposizione Internazionale delle Industrie e del Lavoro in Turin, Italy in 1911. It is his only surviving church in the city.

The church is one of the few Catholic churches in New York City with a dome, and only one of two – the other being St. Patrick's Cathedral – with stained glass windows from the glass studios of Chartres. The building was designated a city landmark in 1969, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 along with its rectory.[2] From 1995 to 1996 the interior and exterior were both restored and renovated.

Started in 1882 in a rented hall above a stable, the congregation has been through three buildings at two locations. St. Jean Baptiste High School was started on the grounds as an elementary school by nuns of the Congregation of Notre Dame in 1886. In the late 19th century, an exposure by a visiting priest of a relic of St. Anne, intended for one night, grew into a three-week event during which many miracle cures were alleged by thousands of pilgrims who crowded the church; as a result, the church now has its own shrine to the saint, which led to a failed effort to get it designated a basilica. In 1900 it passed from the control of the founding Fathers of Mercy to the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, who introduced Eucharistic adoration as a worship style.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:27 9301 181 1982 6377 7661 709

-

Prairie Churches

-

Incorruptible Saints

-

The Marist Brothers 125th Anniversary Photo Album

-

Most expensive chapel in Europe in Roca Church, Lisbon

-

Homily 04-07-2011 - Fr. Anthony Mary, MFVA - St. John Baptist de la Salle, Priest

Transcription

(choir) Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound (Tom Isern) All these steeples, the vertical spikes in our prairie horizons. They look like exclamation points, but I think maybe they're question marks. Where did all these churches come from? Who built them, and where did those people go to? And what does it mean, when every other material expression of who those people were is gone, but the steeples remain? They're expressions of faith I'm sure, but I think maybe more than one kind of faith. And that leaves us to contemplate not only what we can learn about these prairie chuhes, but what we can learn from them. ...was blind but now I see. (woman) Production funding for "Prairie Churches" is provided by grants from... and by... [piano plays softly] (Loretta Bernhoft) My father was baptized, confirmed, married, and buried through this church. This has been where I was baptized, confirmed, married, and expect to be buried from. Vikur Lutheran Church was founded by immigrants from Iceland, and it's 125 years old. It unfortunately, these days is used quite often for funerals. We don't have a lot of baptisms and weddings anymore, again, because of rural declining population, but we have some dedicated people who want to make sure that we keep the building in good shape. [acoustic guitar plays] As we were working on the kneeling rail for the altar, we needed to take off the pad and preserve the fabric so we could resow a new kneeling pad, and when we pulled the old kneeling pad away, we learned that for over 100 years people have been kneeling on straw. There are times when you're doing projects like this that it really takes you back to what our ancestors had to work with and how they struggled to do the best they can with what they had and obviously did a beautiful job. When the settlers came and first set down their roots here, their main social activity or event was a gathering for worship services. So the church was the focus of their social life as well as their spiritual life. And we've really come full circle because we don't have a school anymore. We've lost a lot of the businesses that used to be here, so really, now our church is once again not only our spiritual life, but our social life because that's where we see people. If we only see them once a week, we see them in church. So that remains a a very strong part of our community, and maybe that's part of the reason we would hate to see the churches close, because then we may all go in different directions to worship, and that would further break those ties of the small rural community which we don't want to see happening. [choir sings a wordless melody] (Tom Isern) I think for most people who are caring for country churches, they're doing it as an homage. They had ancestors or predecessors in the community that they thk should be remembered, and that church is the material remembrance from those people. But I have to say in some cases it is just pure cussed stubbornness that has kept them going! There have been a family or a couple of families that say, we're not gonna let the place die. Many times with a church that's completely lost its constituency, it does come down to one or a very few, and a person can do that when you think about it because these churches have lost cash value, and people will buy a country church and say, I'm going to see that it stays around. Often they don't have the means to do the rehabilitation themselves, but you can stop a wrecking ball yourself. Rehabilitating and maintaining a country church has a lot of investment in terms of sweat equity involved. It doesn't necessarily require enormous outlays of cash, and the groups that you see trying to restore and maintain rural churches, you don't find them conducting massive capital campaigns. They rely heavily on volunteers, and they scrounge materials. It's really pretty heartening what people can accomplish, and if you can keep a church tight-- you know the basics for keeping a building together. It's the roof and the foundation. If you can keep those essentials together, you can basically put the church into safekeeping. Well, I've had a hand myself in helping to preserve some of the prairie churches in North Dakota, and I'd have to say that's a point of pride, and I think it's worth doing, not just because of the purposes of the people immediately involved with that particular church but because we hold these in trust. Of course, I'm a believer in the future of the northern plains, and I actually believe there will be a realized purpose for these buildings if nothing else because they make a place a place. (man) We pray in Jesus' name, Ame. You may be seated. I have no doubt that large numbers of prairie churches can be saved, but it depends on people believing there's some reason to save them. It's not a matter of shortage of resources. It's a matter of shortage of faith. The prairie churches are just a symbol of the way things are on the northern plains in that we have more history than we have people and taking care of our history, in particular our material history then, it sufferers just from the lack of available people. It's a logistical problem. I happen to have faith things will work out better in the future, and if we gamble some resources on making that happen, have we lost that much? Won't we feel the better for having done it in the present anyway? Let's invest a little faith. [piano plays "Faith of our Fathers"] This church was closed in 1984 over Christmas service. I was the youngest member of the congregation. In 1995, we had an auction sale. I bought a lot of the furnishings in here-- the pews, the altar, the baptism font. I used my own money. I was single at that time, and it was close to about $4000 I spent on furnishings. They decided, well, if you're serious about buying the furnishings, maybe you want to buy the church? So I bought the church from the cemetery association, and we kept it. I got married probably within 2 months after that, so my wife had inherited this little project too, and she was very supportive of that. It gets difficult sometimes, the financial part of it. It's a big building. It's a lot of work sometimes, and too, as a farmer trying to save time to work on the church, do your farming, it's hard to manage sometimes. It means a lot to our family. This church was organized over at my farm with my great grandparents. We were there at the beginning and also at the very end. We'd kept it, not just for our family, but for other families to use and to visit. Usually, once a year, we had a Christmas service or a summer service. We've had baptisms, we've had a wedding. We do get a handful of visitors every year saying that "I was baptized here." "I was married here." "I had my confirmation here." So it's a nice thing to see that they like it, and they appreciate it. There is a lot of memories inside these walls. There's a lot of memories. This has been a very rewarding project. I enjoy it. I enjoy seeing the church. I enjoy driving by it. Even when you're working out in the field, it's nice to see the church there. This is where I can see for miles away and say okay, there's the church, I know where I'm at. This is my lighthouse on the prairie. [piano plays "How Great Thou Art"] [orchestra plays] (woman) Hallelujah (Gerald Paliwor) Every time you're driving along and you see a church that looks very familiar if you check into the history of it, a lot of the times, you'll find the name Father Philip Ruh associated with that church. He was a very motivated individual, as you might guess by the design of the building and the adjacent grotto, and as well, he's credited with over 40 works in Canada. He was a self-taught architect. He didn't have any formal training in architecture. He was just very well read, and as I mentioned, he was obviously a very motivated individual because you look at some of his works and you imagine that, how would you even go about designing a place like this? Well he was, like I say, obviously a quite an intelligent fellow. Now, he was originally a Roman Catholic priest from Alsace-Lorraine, but due to the shortage of Ukrainian Catholic missionaries in Canada, he was asked to convert to the Eastern rite. So he was sent to the Ukraine for several years, where he learned the language, then he migrated to Canada. How he ended up in Cook's Creek, the faithful of the area had heard of Father Ruh's prowess as an architect and had petitioned to have him come to Cook's Creek to help build a new church. The Bishop sent him out here to have a look. His exact words were, "What a God forsaken place this is!" He wrote back to the Bishop, are you sure this is what you want me to do, and the Bishop replied yes, this is where you will serve. So he said it was not his will that he be in Cook's Creek, but it is "The Will" that I be here so I shall serve. Now, the interesting thing is-- that was in 1930 that he arrived, and they started building the church, and he was the resident priest until 1962 when he passed away. So we presume the place kind of grew on him a little bit. Some considered him quite gruff and quite forward and abrupt, but if you look at any project of great scale, usually the person that's driving the project has to be a very take-charge individual. So for some he might have been a little on the rough side. Imagine trying to get a group of volunteers moving in a direction on a project, not only such a large project, but for such a long time-- we're talking 22 years. If you talk to the old-timers of the area, like my father, and even today, I was talking with him and he was telling stories of when he was 14 years old, helping to build the church, and how Father Ruh would be pitching in, and his hands, Father Ruh's hands, were much rougher than any of the other laborers because he was always, always a very hands-on laborer. He didn't supervise the job just. He also was involved with the pitching and the throwing of whatever materials were required. He had his lighter moments as well, and he, well, to put it bluntly, had some of the best moonshine in the area! [laughs] And he was known for it! So quite a character when you get right down to it. It started in 1930, and there literally was no work to be found in The Depression. They would donate their labor to the church, and that was how the church was constructed. Another interesting note was there was no machinery allowed in the building of the church, not even a cement mixer. So when you look at everything in the church and imagine how could that be built by hand? Well, that's exactly how it was built. Father Ruh was very strict that it be built by the hand of man for the Glory of God. So that was your "hammer and a nail, shovel, and a pail" was the tools of the trade. There was a lot of innovative thinking when the structure was being built how to make it look like marble, and the pillars outside and all that, and a lot of it was local materials they were able to come up with and some very clever work in the design of it. He realized not to overstep your bounds 'cause in his own writings, it was "slow and sure," better than "speedy and bankrupt," especially at that time when resources were strained, moneywise. And manpowerwise, he worked with what was available, and he raised what was needed by whatever means, be it dances, bingo's-- you name it. He raised funds, and he built as the funds were available. He said there would be no debt incurred in the building of the church, and they never did. Now, it took 22 years to build. It was completed in 1952, then it was consecrated in 1954 and dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. (woman) Ave Maria gratia plena, Maria gratia plena, Maria gratia plena. Ave ave Dominus. Dominus te-cum. Benedicta tu in mulieribus. Et benedictus. Et benedictus fructus ventris, Ventris tui Iesus. Ave Maria. [piano plays] (Rolf Berg) This has been our home all our life. My wife and I both have attended this church. We were both baptized here just a couple weeks apart and both went to Sunday school here, were confirmed in the same class, and my hope and prayer is that it can continue running in the years ahead. This church is the Viking Lutheran Church. We had the dedication of this building in 1909. At that time, we were considered the biggest rural church, Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, between Minneapolis and the West Coast. I think anytime we have people come here and tour, they can't believe the windows that are here, and the rare thing about them is how they got here without any problem. When you stop and think about that, you marvel at what these people have done here and the work that they've done to build this church. Most of the material came on train and was carted by horses! And these picture windows, and all the things in this church were brought here on wagon boxes. [orchestra plays "the Hallelujah Chorus"] I went to Bismarck, and I went up to the historical society, and I said, I'd like to have you see something in Maddock. I'll never forget that day 'cause Lou Hefernil walked in, and he looked up at the chandelier and looked at that window and looked at that window. He said "Rolf, you don't know what you've got here, do you?" I says "Lou, that's why you're here." Well he said, "The chandelier and the windows," he said, "I'm considering they're more valuable than the rest of the building you have here. The value on them is unbelievable." So in 1979, we were listed on The National Registry. One thing I notice about our rural churches, the membership of these churches are more permanent. They want to keep what they've got. The people all feel a part of the building itself, and I think that's why the building is still here and maintained as such because they're very proud of the architecture, the stained-glass windows, and then the fact that many of them, it's their grandpa and grandmas that have done this work. And so all they're doing is continuing, not because they feel they have to, but because they want to continue the heritage that was here down through the years. [orchestra plays "the Hallelujah Chorus"] [pipe organ plays "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"] (Ronald Ramsay) Buildings are total sensory experiences. Too often because architecture involves objects, we tend to think of them as exclusively visual things. They're not. Next time we go to a religious service, start to pay attention to all 5 of your senses. Don't just look at the building, but listen to it, smell it, and there are even instances where we taste buildings, especially churches that, old masonry churches, that begin to develop rising damp, and you walk in and you can almost taste the mildew in it. Coming to church and attending a service is a multisensory experience. When people began arriving here in the middle of the 19th century, they were bringing a certain expectation about what a church was supposed to look like, came with a kind of architectural baggage of the motherland, and whether you built that in wood or masonry or tin or stucco didn't really matter very much. It was the form. You can read a building from the outside, what's going on on the inside, and in many instances, you can probably predict who's inside. Certainly the Scandinavian churches have a kind of sparseness to them. I think if you go back to the history of the Scandinavian immigration, many of the people who came, especially from Norway, were Hauge Lutherans, and Hauge Lutheranism was a Lutheranism of deprivation. It was learning how to find sanctity in having less rather than having more. And so all these Hauge Lutherans came here and built churches that were lean and spare and stripped of ornamentation because from their theological perspective, ornament was sin. A pair of towers, either identical or mismatched, probably a pretty good indication that Roman Catholics are in there. Coming from Eastern Europe, most of the Eastern churches took as their pattern the Orthodox pattern of Eastern Christianity with domes of one sort or another that were not nearly as prominent in the West. And so here we have another ethnic group bringing an expectation with them of what a church is supposed to look like. It's supposed to look like the ones back home. The building is, after all, a glove, and the hand that's in the glove are the people and the liturgical practice. The glove is going to take its form from the hand, and it's important as a people that we keep certain examples to remind us of where we've come from and how far we've come and how far perhaps we have yet to go. When you look at the building like this, where at the time, there were maybe 50 or 60 people in the community, somebody had a lot of vision to build something like that. I'm sure some of them must've called them, I don't know, maybe "crazy" to build such a big place that would hold 500 people when there's only 50 or 60 people. But it's often filled up. Our church is Saint Joachim Chevaliers De La Broquerie. It was completed in 1901. The bricks were manufactured just outside of town here. I know that the wood was made, cut, and sawed by the first pioneers, so we're very proud of our church. You can see the architecture is something that we're very proud of. I don't know how they did it, you know, when there wasn't as many people to maintain a place like this. It must've been difficult. Now it's quite costly just to heat it. I remember when I was a kid, they didn't heat the church like all week in the wintertime. It was just wood furnaces, and the wood was supplied by the parishioners. In some places I've seen some beautiful churches that they said ah, it's not worth fixing, it's too old, so they let it go, and then they have to tear it down and build something else, and I think it's something lost. We're lucky that we still have our church. It's part of our culture, of our heritage so it's nice to keep those things. If you throw away this, you throw away part of history. [pipe organ plays "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring] (Burt Imhoff) We have people come here from all over the world, and they can't figure out what this art is doing out here in the middle of nowhere. Did he donate pictures to churches in Saskatchewan? Definitely. A lot of churches he did for free of charge. My grandfather originally came from Germany. From Germany, he immigrated to Reading, Pennsylvania. From Reading, Pennsylvania, at his late 40's, he moved up here to St. Walburg, Saskatchewan. He came up here on a hunting trip with some people he knew, and there was inexpensive land up here at that time, so he bought land, and he liked the area, and he moved up here. They moved in 1914. He hired other people to work his land and to break it because he wasn't a farmer. He was an artist, and that's all he did. He decorated a lot of churches. He was trained in art schools in Holland, Dusseldorf in Germany. Most of his work was done in the States, in the Dakotas and mostly around Pennsylvania. The list we have of all the churches he did was over 90, but obviously, he did a lot more than that because there are some churches that he did that we haven't got lists of. We're at the Imhoff studio, the working gallery of my husband's grandfather Berthold Von Imhoff. He started all these paintings in charcoal first, and then he would put 3 coats of oil. And he also only painted by the north light because he also had to mix his own colors. Couldn't buy the colors that he used at that time. That's why all the windows in this studio are on the north side, and he could get the true colors that way. When they would contact him to do a church, he had numerous amounts of small paintings, like you see them all around the side over here. He'd take those with him, and they would pick out what they wanted in a church, and then he would paint it in life size. All the pictures that he did were done right in this building, and then they were taken down to the church and then put up, unless it was a curved area like over an altar or a curved dome or something, then the canvases were put up, and they were painted right in the building right there. Even though they lived up here in Saskatchewan, they would go back to the States and do projects. When they did the large church in Reading, Pennsylvania, they moved down there. We're in the St. Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church. This is undoubtedly Berthold Imhoff's masterpiece. At the top of the ceiling here are 224 life-sized figures processing towards the altar. In the sanctuary, we see St. Paul preaching to the people of the East and St. Peter preaching to the peoples of the West. Berthold received a commission from St. Peter's Church to paint this procession of Saints, and he did this at his studio at St. Walburg, Saskatchewan, and put the paintings on a train, and he and his son Carl came down here and installed the paintings in approximately the mid 1920's. When he moved up here, yeah, he was well off, but everything he made in churches, he would put back in his canvases. He painted when he didn't have commissions. All the ones you see in here today, he just painted to paint-- no sale for him-- He never did sell a picture. He never painted a picture to sell. It was just churches that he was commissioned to do. In the United States, he did very well. Everything he had, he paid for with the work of his artwork. Much of the work he did in the churches in Saskatchewan, often they were donated. It was important to him that they had something that reminded them maybe of their homeland 'cause a lot of these were European people, and the churches were decorated beautifully there, and so he would give them a gift that way, a reminder of their homeland. And also even in worship, the art helped them because it drew them to thinking of things that were say, removed from everyday life. A decoration from the Pope came in 1937. He was knighted with the Knighthood of Saint Gregory the Great. It was befitting that knighthood was bestowed on him because Saint Gregory the Great was noted for his charity. He used his wealth to the good of everybody. When he died, he was not well off at all. He was in fact very poor, so for helping with Mrs. Imhoff, his wife gave a painting to the undertaker because there was no money. He was a very spiritual person, and I wouldn't say so much religious as very faithful. He had a faith, and he had a goodness in him. I mean, he had to have to have given so much, not only in his artwork but in other charity too. Like if somebody was hard up, he would help them out, and that was not known until after he died. (choir) Faith of our fathers, living still, in spite of dungeon, fire, and sword. Oh, how our hearts beat high with joy Whene'er we hear that glorious Word! Faith of our fathers, holy faith. We will be true to thee till death. [resonant clanging of a churchbell] (man) Let us pray. Most high God in the heavens cannot contain, we give you thanks for the gifts of those who have built and maintain this house of prayer. We used to have a membership that was very large here. (man) You made all things. (John Boen) We have a picture down in the basement of one of the special occasions up here. That photo is approximately 3 feet long to cover the number of people here, and they were all church members. And now when we took one about 10 years ago, that's about 10 by 12 inches square. We are struggling to keep the church going. It has been here for 134 years, so we'll try and make it go for a few more. I believe my great grandfather was a member of this church. I've been a member here all my life. Betty and I were married here, and our 2 daughters were married here. [piano plays softly] It's had many good happy events, but it'll be a shame to board up the windows. I hope it doesn't happen in my day. [violin plays softly] (Sheldon Green) Saints Peter and Paul Church in Strasburg, North Dakota, really is symbolic of the immigrant experience. Yes, they came to the New World, and they came to start fresh, but they also came as people of faith just like they had been in the Ukraine. They did not leave that behind. The Strasburg church was built in 1909 to 1911 at a cost of $45,000, so at that time that was the finest building for miles around. The feeling among the German Catholics was only the best house for God, and so there was this tradition that the church was the finest that they could possibly build. We're going to spare no expense. In fact, there was a real feeling that we must sacrifice personally, or our family must, in order to build this magnificent house. When Saints Peter and Paul Church was being built, not everyone was 100% behind donating their own labor to build the church. Some of them thought just if I pay the money, I can stay at home and farm. And so there were several vocal farmers that said, why should I give up my time to build this church when my work is needed at home? And it wasn't more than a few days after that that severe hailstorms swept through the area, and the hail decimated crops far and wide. Generally they destroyed the fields of the people who were vocal about not wanting to give their labor to the church. The people who had sent laborers in or sent sons or fathers in to work on the church, somehow their crops were spared. And so the following day, the work site at the church was swelled with all these farmers wanting to come in and work. Apparently, they didn't want to run the risk of hail again. As soon as the building was finished, a lot of the parishioners started donating statuary art in honor of an immigrant or a family member. Quickly the church filled. There's something like a dozen angels. There's 10 statues to saints. There's the glass windows. Most of these were given in the name of someone that was being honored or recalled. There was a priest in Strasburg in the 1980's that wanted to remove the high altar, and during the congregational meeting when this was put out, there was a voice from the back said, "If that altar moves, your backside will be filled with buckshot!" And so the diocese moved that priest to a different church. The parishioners in Strasburg wanted to maintain that link with their European past and honoring the pioneers that came. They didn't want to touch anything. Over and over and over again, the people who are most familiar with these rural heritage gems, are the least impressed by them because they're so used to them. They've seen them all their lives, and they seem to have an impression that it's the same way all over. They're everywhere, so why should we save this one? It takes someone who's not from the area to say no, this is really special. You guys really have to do something with this. The Manitoba Prairie Churches Project has 2 principle funders. It's the Thomas Sill Foundation of Winnipeg and the Kaplan Fund out of New York City. Being with the Manitoba Culture Heritage and Tourism Historic Resources Branch, we often help people when they come to us to try and organize a project to save something. I got a call from the Kaplan Fund in New York City, and they were funding a prairie churches program in Saskatchewan and North Dakota. It was like a cross-border northern plains thing that they were doing, and they were saying well, do you have any interest in churches in Manitoba? Oh, do we have an interest in churches? We probably have the best variety of country churches on the whole continent. You have to come see them. Here we've got Mennonites and Poles and Icelanders. It's just a wonderful, wonderful variety, and the churches are part of that cultural landscape which again, sadly, is disappearing. And if you are fortunate enough to drive around and see some of these, you'll see what I mean. They're all different. Some are just spectacular churches, and I don't know who the architects were. Some of them look like Turkish mosques. Some of them look like simple little gable roofs with a teeny-weeny little dome where the mammas and the grandmas and the grandpas and the grandkids all came to help out. We've got quite a few churches that are preserved. There is a couple of churches not far from here that haven't been used as churches since the mid '60's, and they're just now religious landmarks. The people who used to go there or have family buried there, they go back, and they cut the grass and paint the church every 10 years and roof it, and it hasn't been used like for 30 years as a church, but it's this wonderful landmark in the countryside attesting to the settlers and what once was here. So even though it's only used once a year or not at all doesn't mean you can't save it as a landmark. So every little one's a big success because it was part of the cultural landscape, and it would be really, really sad to have what used to be a landscape dotted with grain elevators and churches and domes poking up over the tree line than to have nothing on the landscape. So things like this are very important to preserve. [choir sings] (Dot Connolly) We were sitting at the restaurant, a bunch of women and myself, and somebody came in and sad vandals have broken into the church. We walked through the doo, and as you walk in, there's a large red carpe. In the center of the carpet, the cross lay on the floor smashed in 2. There was cigarette butts, and there were pop cans and beer cans. The icons on the wall as you go into the iconostas were stabbed in the heart. The people felt such a feeling of sadness. It was just overwhelming to think here's another thing that is lost, another part of the community, sort of the final nail in the coffin. I had my granddaughter with me, and she said Grandma, why don't you fix it up? Why don't you patch the roo, paint the walls, and patch up the cracks? And I thought what do we have to lose? We still all figured that there was no way, but we thought, well, we'll try. And so we tried one step and the next step and the next step. The first thing to do was the basement which was the biggest project. We got quotes that that was going to be $80,000. Well, how could we get $80,000? But we wrote to the governmen, Hugh Packland in Winnipeg with the Winnipeg Foundation and the Kaplan Fund, which of all is the Welch's grapefruit people out of New York City. Well, I would go and find these people, and then I'd come back in the community and say the Welch's grapefruit people out of New York City want to put some money into our church. And people would just shake their head. "Why are you putting money into that old church when there's so much else to do?" "Why don't you fix the roads?" So the first year they thought we were crazy. The 2nd year they were pretty sure we were crazy. We're going into our 5th year, and the local people are starting to think that ths is something pretty fantastc that the community did. This church now is coming alive once again. That first service that we had was an amazing thing to happe. The old people who were sure that they had lost their church, that they would never have a service in that church again, they came, and in the center, they put a picture of the Madonna, and people come up the carpt on their knees to kiss that picture. And there were the old people, the local men, the big macho men that you see in the coffee shop every morning, on their knees with tears in their eyes coming to kiss that pictue because they thought that they would never see that happen. [woman sings, with piano accompaniment] Our Father Which art in heaven Hallowed be thy name Thy kingdom come Thy will be done On earth as it is in heaven Give us this day our daily bread And forgive us our debts As we forgive our debtor And lead us not into temptation But deliver us from evil For Thine is the kingdom And the power And the glory forever, Amen. (choir) Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound. [choir hums the melody] (woman) Production funding for "Prairie Churches" is provided by grants from... ...and by the members of... To order a DVD...

Property

The church is located on the east side of Lexington Avenue at 76th Street. The building takes up most of the 20,000-square-foot (1,900 m2) lot, with the rectory on the south side, facing East 75th Street.[5] The area is densely developed. St. Jean Baptiste High School, run by the church, is on the other side of 75th Street. Lenox Hill Hospital is nearby.

Exterior

The building, which opened in the spring of 1913, is faced in limestone. Its west (front) facade is rich in ornament. The main entrance is located in a pedimented portico with full entablature on a high plinth supported by four Corinthian columns. This design is echoed with smaller pediments on each of the side entrances above carved festoon and scroll motifs.[5]

Above a broad cornice, twin bell towers rise to a total height of 150 feet (46 m) at the corners. Their lower stages with canted corners have round-arched openings framed by pilasters. Above them an open circle of Corinthian columns supports a ribbed dome, topped by a smaller version of the top with a cross. These are echoes of the larger dome in the middle of the church that rises to 172 feet (52 m). Between the two towers, on the parapet, a statue of angels supporting a globe echoes the pediment below. The gabled, gently pitched roofs are sheathed in copper.[5]

On either side of the front facade, projecting entrance bays with windows are topped with a statue of an angel blowing a trumpet. The side elevations, of which only the north is visible from the street, have high round-arched windows and continue the cornice at the roofline. Pediments similar to those on the front grace the second story above the windows on either end of the transept.[5]

Interior

Inside, the barrel-vaulted nave is separated from the vaulted aisles by an arcade of tall Corinthian columns; the vault springs from the entablature. All the vaults, ribs and arches are richly decorated with Florentine-style reliefs. The column capitals and fluting are also gilded. The center of the nave vault has trompe-l'œil paintings of the heavens; an elaborate Florentine-style floral pattern decorates the interior of the dome.[5]

Against the apse triforium on the east wall of the church stands the high altar with a mosaic half-dome, statues, and smaller bas-relief sculptures. The shrine of St. Anne is located here. A six-foot-tall (2 m) monstrance, for showing the Eucharist to believers for prayer and contemplation, crowns the altar. Smaller baldachins shelter the smaller altars on the sides. To the left is an altar to Mary of Carrara marble; to the right is a similar one honoring St. Joseph. At the transept corners are smaller altars to Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament founder St. Peter Julian Eymard, with a relic in a case below; the other corner's altar is to St. Anthony of Padua.[6] The walls and ceilings are otherwise decorated with paintings in the Baroque style.[5]

The stained glass windows and high altar were brought to New York from Chartres, France and Italy, respectively, following World War I. On three levels, from the dome to the nave, the windows portray the Twelve Apostles, scenes from the Old Testament which prefigure the Christian sacrament of the Eucharist, and events in the life and ministry of Jesus, including the Last Supper and the institution of the Eucharist and the Easter appearance of Christ to the disciples at Emmaus. The high altar is 50 feet (15 m) tall. A team of artisans accompanied the various pieces of the altar from Italy and reassembled it in the sanctuary.[6]

Under the dome is the altar table, made of white marble. At the center of the frontal is a Christogram, IHS, from the first three letters of Jesus (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ) in Greek. The pews, choir stalls, and confessionals are of oak and are elaborately carved. Eucharistic images, especially wheat shocks and clusters of grapes, are prominent throughout the building.[6]

A restoration of the interior was completed in November 1998.

Associated structures

The Rev. A. Letellier, rector, had a five-storey brick and stone rectory at 170–190 East 76th Street and 1067 Lexington Avenue built in 1911 to designs by Nicholas Serracino of 1170 Broadway for $80,000. The rectory is also an Italian Renaissance-style palazzo. Five stories high, it is faced in white brick with granite steps leading down to 76th Street. The seven-bay north (front) facade features limestone voussoirs crowning each window. The end bays project slightly and are set off with large pilasters. The ground floor is rusticated. Limestone string courses are above the second and fourth stories, with a plain entablature and overhanging cornice at the roofline.[5] There have been few alterations to the exterior. The interior, by contrast, has been extensively remodeled over time. Only the oak woodwork remains from the original building.[5]

The Most Rev. Pat. J. Hayes had a four-storey brick school with a tile roof at 163–173 East 75th built in 1925 to designs by Robert J. Reiley of 50 East 41st Street for $300,000. A five-storey brick brothers apartment building at 194 East 76th Street, was built in 1930 to designs by Robert J. Reiley of 50 East 41st Street for $70,000 to 90,000. A five-storey brick sisters apartment house at 163–175 East 75th Street and 170–198 East 76th Street and 1061–1071 Lexington Avenue was built in 1931 to designs by Robert J. Reiley of 50 East 41st Street for $125,000.[7]

History

From its origins in a rented hall above a stable[8] with an almost exclusively French Canadian congregation, St. Jean Baptiste has grown to be one of New York's most distinctive Catholic churches. It has been through three buildings in two locations and under the care of two different orders of priests.

1841–82: Establishment of parish

In the early 19th century, one in every nine New Yorkers was of French descent. Most were Huguenots, Protestant refugees from the French Revolution, but there were some Catholics. In 1841, Bishop de Forbin-Janson, on a missionary tour to the United States for the Fathers of Mercy, lamented that French-American Catholics in New York City had not been as devoted to raising churches in their national customs as Irish and Italian immigrants had. The community responded to this challenge, and accordingly the first Church of St. Vincent de Paul was opened the next year on Canal Street.[9]

That church grew, and moved north to 23rd Street in 1868. A French Canadian immigrant community had begun to flourish in Yorkville at that time, and found it trying to make the trip downtown for services. A missionary to this community found that services closer to home would be beneficial, similar to those the Jesuits at what is now St. Ignatius Loyola had organized for Yorkville's Germans. The order's provincial gave his support for the establishment of a national parish, and a meeting of the immigrants' St. Jean Societé in 1881 raised $12 ($400 in contemporary dollars[10]) to that end. This is considered the beginning of the church's history.[9]

A chapel was established in a rented hall above a stable on East 77th Street. The constant noise from the horses downstairs earned the chapel the nickname "Crib of Bethlehem" from congregants. A few months later, Cardinal John McCloskey, Archbishop of the Diocese of New York and the first American cardinal, granted permission to build a church, formalizing the parish. The new parish was able to raise $14,000 ($442,000 in contemporary dollars[10]) to buy a property on the north side of East 76th Street in 1882. By the end of the year Coadjutor Archbishop (later full Archbishop) Michael Corrigan had blessed the new building's cornerstone.[9]

Napoleon LeBrun's design called for a simple Gothic Revival church building, 100 feet (30 m) long by 40 feet (12 m) wide, with room for 600. Its projected cost was $20,000 ($654,000 in contemporary dollars[10]) but it soon ran into difficulties when problems with using the "crib of Bethlehem" forced the use of the unfinished church's basement during Lent in 1883. Archbishop Corrigan had to take title to the church to save it.[9]

1882–1900: First church and St. Anne's shrine

The new church was successful not only with its intended French Canadian community, but with all Catholics on the Upper East Side. Many were servants in the nearby houses of the city's wealthier residents and had to report for their jobs early, thus appreciating a nearby church where they could first attend Mass. In 1886, nuns from the Congregation of Notre Dame, founded in colonial Montreal in the mid-17th century, came to establish an elementary school.[9]

In 1892, the church inadvertently became a shrine of St. Anne. A Canadian priest, Father J.C. Marquis, dropped in at the rectory unexpectedly on May 1, needing a place to stay while he carried a relic of the saint that Pope Leo XIII had given him back to Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec. The pastor at the time asked him to expose it to the parishioners during vespers that evening. Marquis did so, as he would continue to Quebec the next day.[9]

News that the relic would be exposed soon reached the community, and a large crowd showed up for evening services. When a young man having an epileptic seizure was touched by it, his convulsions ceased. That apparent miracle was widely reported and even more crowds showed up, many expecting cures. The pastor asked Marquis to stay for a few more days with the relic to satisfy the many pilgrims.[9]

His stay would be extended to three weeks as thousands of pilgrims came. As he finally left on May 20, crowds bade the relic farewell and asked that she return again for good next time. Father Marquis was so impressed that he promised to obtain a relic for St. Jean. With the permission of Cardinal Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, he divided the relic once he had reached Sainte-Anne and returned to New York with it in July. More crowds came, more miracles were reported, and Marquis reported favorably on this to the pope. As a result, he was able to make a return trip to the shrine of St. Anne in Apt, France, and brought a relic back specifically for St. Jean Baptiste.[9]

1900–18: Change in leadership and new church

In 1900 the efforts of a wealthy local Catholic activist, Eliza Lummis, brought the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament (SSS), an international religious order of priests, brothers, and deacons founded by St. Peter Julian Eymard in Paris in 1856, to New York. They were unable to find a center for their work, but often attended Mass and resided at the St. Jean Baptiste rectory. One day, the pastor joked to the Blessed Sacrament priests that if they could not find a church, he'd just have to give them his. That remark got back to Archbishop Corrigan, who informed St. Jean Baptiste's pastor the very next day that he was putting St. Jean Baptiste under the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament's control. Throughout the rest of the year the interior of the LeBrun church was altered to be more in keeping with the Congregation's Eucharistic style of worship.[9]

The continuous exposure of the Sacrament, and the availability of daily confessions and early Mass at what was known as "Old St. Jean's" led to another increase in the size of the congregation. Corrigan had said at the first Mass that he expected the church would soon be outgrown and a new one built more worthy of Christ. During one Mass, financier and philanthropist Thomas Fortune Ryan, a Virginian who converted to Catholicism as a young man and who, with his wife Ida Barry Ryan, supported the construction of churches, schools, and other charitable institutions along the Eastern Seaboard, arrived late and had to stand. He preferred St. Jean to the larger churches closer to his Fifth Avenue mansion, and often attended services there. He heard Father Arthur Letellier, the new pastor, ask the congregation's prayers for a new church, and afterwards asked how much one would cost. "About $300,000" ($10.2 million in contemporary dollars[10]) he was told. "Very well", he replied. "Have your plans made and I will pay for the church".[9]

At first Ryan had wanted a church similar in size to the existing one, but Letellier persuaded him it was time for a church with room for 1,200 people, twice the LeBrun church's capacity. Italian architect Nicholas Serracino, who had been living in New York for the decade, won the commission. He produced a model of a grand Renaissance Revival church with a dome and classically inspired front facade.[9] His design reflected Catholics' search for a unique architectural style for their churches, since the Gothic Revival and neo-Gothic designs had become associated with Protestant churches.[11] In 1911 Serracino's renderings of the unfinished church won first prize at the International Exhibition in Turin.[9]

Ryan was initially skeptical of the dome, but when he saw how it won praise on a model of Serracino's design he authorized the additional $43,000 ($1.41 million in contemporary dollars[10]) for it. This would not be the only cost overrun. Serracino underestimated the costs of local labor and materials. Bedrock was 25 feet (7.6 m) deeper than originally believed because of the marshes filled in when the area was originally developed in the mid-19th century. The cost of the foundation increased eightfold as a result, and plans to gild the dome and finish the interior with marble had to be canceled. The widening of Lexington Avenue also forced Serracino to scale back his original plans for a grand triumphal arch portico with full-width steps. Ryan continued to provide funds for a final total cost of $600,000 ($18.5 million in contemporary dollars[10]).[9]

The rectory, also designed by Serracino, was built and opened in 1911. The lower church in the basement was finished and consecrated in 1913 by Camillus Paul Maes, bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Covington, who had been the Congregation's strongest supporter in the U.S. Early in the following year, he attended the first Mass celebrated in the upper church, even before the walls and ceilings were finished, by Father Letellier. Cardinal John Murphy Farley, the archbishop, spoke at the end of the service and read a congratulatory telegram from Pope Pius X.[9]

1918–87: The church in a changing city

Within a few years of its construction, the new church twice became a crime scene. The first occasion was the night of November 30, 1918, when police pursued a man named Charles George into the church following a carjacking. The police and George had been exchanging gunfire, and it continued as he ran up the stairs into the choir. When he ran out of ammunition, he surrendered. Several women who had been praying in the church at the time had to be treated for hysteria.[12] Almost a year later, on November 29, 1919, Cecilia Simon, a maid at an East 56th Street home, was arrested in the church when she knocked statuary and a candelabra valued at $3,000 ($53,000 in contemporary dollars[10]) onto the floor and shattering them after a funeral service. She was taken to Bellevue Hospital for observation. While apparently a devout enough Catholic to be a daily communicant, she was not a member of the church. At services there the previous Sunday, investigators found that in a collection envelope she had placed a note registering her objection to the arrangement on the altar. A coworker said that she had been acting strangely all week and had said she was going to "do some good work" at church that day.[13]

In 1920 Mayor John Francis Hylan and Governor Al Smith were among the 100,000 Catholics who signed a petition to the new pope, Benedict XV, to designate St. Jean Baptiste a basilica.[14] It failed. Later in the decade the church's interior decoration was gradually installed and finished. Ryan's funeral was held in the church he had paid so much to build in 1928.[15] In 1929 the sisters of Notre Dame opened a high school to go with the elementary school they had been running for almost 40 years.[9]

The interior of the church was modified slightly in the 1950s during renovations. The Requiem Mass for Ryan's grandson Clendenin J. Ryan, publisher of The American Mercury, was held there in 1957 after his suicide.[16] In the 1960s, following Vatican II, the church began to change, as much due to the changing demographics of its parish as the council. It stopped celebrating Mass in French, and the elementary school was closed nearly ninety years after its founding.[9] In 1969 the city made the church one of its first designated landmarks. The next year crime once again intruded into the church when an elderly woman was stabbed on a staircase within by three youths.[17]

1987–present: Renovation

In 1989 stones from the facade fell onto the Lexington Avenue sidewalk. No one was injured, but the church had to erect a wooden shelter to protect pedestrians from potential future incidents. That led to the restoration of the exterior over the next year,[11] part of a $6 million campaign that began in 1987.[18] Work on the stained glass windows proved particularly challenging because the original installers had forced them into spaces too small for them, making them hard to remove. It was necessary to hire more than the usual number of restorers, work overtime and locate the workshop in the dome rather than offsite in order to meet the church's fall 1997 deadlines. For several months during that time services were held in a nearby school auditorium.[19] The renovations were overseen by the firm of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer.[20]

It was financed by the sale of land and air rights over a building formerly used as a convent by the sisters of Notre Dame, who subsequently moved into the upper floors of the rectory. A developer built The Siena, a 73-unit, 31-story luxury condominium tower, on the site.[21] It has been praised by a group of architects including Robert A.M. Stern for complementing the architecture of the adjacent rectory by echoing the church's bell towers and offering "rich sculptural form and lively surface patterning ... to a neighborhood burdened by so many uninspired blocklike apartment buildings"[22]

In 2002, a longtime parishioner, Maryanne Macaluso, alleged that the new pastor, Father Mario Marzocchi, had groped and propositioned her after offering her a secretarial position. After she complained to another priest and took paid leave due to the stress of having to see Father Mazocchi every day, the order had him evaluated by a psychologist who found nothing wrong with him, and then transferred him to a parish in Florida. When she returned to work, she claims the church retaliated against her by cutting her work hours from full-time to part-time after several weeks and giving duties she normally performed to others. When she asked the replacement pastor, Father Anthony Schueller, for full-time work, he informed her that the church could not afford to do so and she requested a letter of termination, putting her in danger of being evicted from her apartment.[23]

After the state denied her unemployment claim on the grounds that she had left work voluntarily, Macaluso filed suit against the church, the order, the Archdiocese of New York, Cardinal Edward Egan, and Father Marzocchi. She alleged negligent hiring and hostile environment sexual harassment. In 2007 Judge Louis York of the New York Supreme Court dismissed her claims, without ruling on the facts, against all but Father Marzocchi, who had not responded.[24]

Programs and services

The church celebrates Mass three times a day and five times on Sunday, with a Saturday night vigil. The Eucharist is exposed for prayer and contemplation at all other times. Confession is available for a half-hour daily and twice on Saturdays. The Liturgy of the Hours is observed twice daily and once on Sundays. Devotions to St. Anne are observed twice on Tuesday with an annual novena observed leading up to her July 26 feast day, to the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament's founder St. Peter Julien Eymard after Thursday's Masses, and to the Sacred Heart of Jesus after Friday evening Mass. The Rosary is prayed at noon Monday through Saturday.[25]

The church's musical ministry is led by its organist, who also directs two choirs, one of volunteers and the other professionals. A thrift shop is run in the basement, next to the community center. A toddler play group and senior group are held there at different times of the week.[26] Also in the basement is the Kathryn Martin Theater, which has hosted a number of musical performances, both church- and non-church-related.[27]

In the broader community, the church, in conjunction with the sisters of Notre Dame, continues to operate St. Jean Baptiste High School for girls. The congregation is a member of the Yorkville Common Pantry and the Neighborhood Coalition for Shelter. The community center is also available for rent to individuals and organizations.[26]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

References

- ^ "NYCLPC Designation Report"

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Lafort, Remigius The Catholic Church in the United States of America: Undertaken to Celebrate the Golden Jubilee of His Holiness, Pope Pius X. Volume 3: The Province of Baltimore and the Province of New York, Section 1: Comprising the Archdiocese of New York and the Diocese of Brooklyn, Buffalo and Ogdensburg Together with some Supplementary Articles on Religious Communities of Women.. (New York City: The Catholic Editing Company, 1914), p.337.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1. p.169

- ^ a b c d e f g h Huckins, Polly (August 1979). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, St. Jean Baptiste Church and Rectory". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Saint Jean Baptiste Catholic Church Tour". St. Jean Baptiste Catholic Church. October 2005. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Office for Metropolitan History Archived February 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, "Manhattan NB Database 1900–1986," (Accessed December 25, 2010).

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12543-7., p.212-213

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Saint Jean Baptiste Catholic Church History". St. Jean Baptiste Church. October 2005. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (December 30, 1990). "Streetscapes: St. Jean Baptiste Church; Restoration on Lexington Ave". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "Police Shoot At Man In A Church; Fugitive, Accused of Auto Theft, Surrenders on Stairs to Choir" (PDF). The New York Times. December 1, 1918. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Woman Wrecks Altar in $1,000,000 Church" (PDF). The New York Times. November 30, 1919. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "New Basilica Sought; Governor and Mayor Sign Petition for St. Jean Baptiste Church" (PDF). The New York Times. January 14, 1920. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "Wall St. Leaders Attend Ryan Rites; Catholic Church Dignitaries Also at Simple Services at St. Jean Baptiste" (pdf). The New York Times. November 27, 1928. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "350 Attend a Mass for Clendenin Ryan". The New York Times. September 15, 1957. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Widow Stabbed in Church On East Side by 3 Youths". The New York Times. October 29, 1970. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "A $600,000 Restoration/Renovation of a Church Interior; A New, Brighter, Palette at St. Jean Baptiste". The New York Times. February 8, 1998. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (July 20, 1997). "Stained Glass at the Speed Of, Er, Light". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ "POSTINGS: 31-Story Building Going Up Next to St. Jean Baptiste on E.76th St.; Condo Rising Beside Church's Dome". The New York Times. March 17, 1996. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "The Siena – 188 East 76th Street". cityrealty.com. 1994–2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Barry, Dan (August 9, 2003). "Another Mass, but Minus One Regular". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Macaluso v. Church of St. Jean Baptiste et al" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2012.; New York Supreme Court; February 27, 2007; retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ "Saint Jean Baptiste Catholic Church Schedule". St. Jean Baptiste Catholic Church. October 2005. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "Saint Jean Baptiste Catholic Church Ministries". St. Jean Baptiste Catholic Church. October 2005. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Saint Jean Baptiste Community Center". St. Jean Baptiste Catholic Church. Retrieved April 13, 2010.