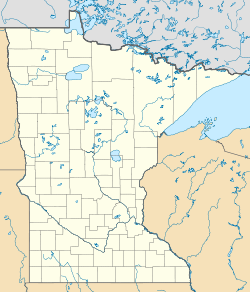

New Dosey Township, Minnesota | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 46°12′36″N 92°21′42″W / 46.21000°N 92.36167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Pine |

| Area | |

| • Total | 112.9 sq mi (292.4 km2) |

| • Land | 112.8 sq mi (292.2 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.2 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,234 ft (376 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 74 |

| • Density | 0.7/sq mi (0.3/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| FIPS code | 27-45484[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0665092[2] |

New Dosey Township is a township in Pine County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 74 at the 2000 census.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/1Views:647

-

Prairie Mosaic 306

Transcription

(woman) "Prairie Mosaic" is funded by-- the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund, with money from the vote of the people of Minnesota on Nov. 4th, 2008; the North Dakota Humanities Council, a nonprofit independent state partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities; the North Dakota Council on the Arts, and by the members of Prairie Public. [bass, drums, and acoustic guitar play in bright rhythm] Hi, I'm Bob Dambach, and welcome to "Prairie Mosaic," a patchwork of stories about the people and the places that contribute to the arts, culture, and history in our region. On this edition, we'll examine if it matters where we eat, and who we eat with, and visit a restored flour mill. We'll take a spin on a potter's wheel and tap our feet to jazz music provided by a big band. Where painters have their brushes and potters have their wheels, bonsai artist Lloyd Harding's tools are snippers, shovels, and the pruning saw. The unusual partnership of bonsai is a work of art made in collaboration between the artist and a tree. [acoustic guitar softly finger-picking] (Lloyd) A bonsai is a tree in a pot. It was started 2500, 3000 years ago in China. You find bonsai growers in clubs throughout the world in almost any country you care to name. The purpose is to grow a tree for aesthetic reasons only. The primary focus of bonsai growing has been the Far East aesthetic. Our Western aesthetic is for fairly rich detailed paintings, artwork, while the Far East aesthetic is concerned more with austerity and simplicity. My wife gave me a bonsai for a birthday present and of course, I put it on the dining room table and admired it and everything and I promptly killed it in three weeks. So I decided I needed to figure out what was wrong here, 'cause I like growing things and it was sort of an insult to my growing powers. It's getting on 18, 19 years now, since I got that first bonsai. I have way too many trees now, but I can't stop. The definition of a bonsai doesn't require that it's a specific tree. I recommend do what the Japanese do, they have trees that grow locally in their area and create bonsai from them. A bonsai is a time-dependent process. It's sort of like a symphony, but it's a symphony of life, of growing. For instance, if you look at the typical structure of an informal bonsai tree or formal bonsai tree, which are styles, you typically have a large lower branch that comes off to one side. You have another branch a little higher up, growing off sort of toward the back to give depth to the tree. And then a third branch that maybe goes off in a different direction, and that variance actually goes all the way up the tree. The bonsai artist prunes these branches to make sure each branch gets sunlight. Cut that thing off, get rid of it. So now we're starting to see the trunk a little bit. Say you prune off one of these lower branches, which I consider the bass instruments in the symphony. They're the low notes, the ones that give it that strength. Sunlight now gets into that area of the trunk, and if it's a tree that'll bud back, you'll get another bud growing somewhere along the trunk. And so you form that to create your bass notes again. One of the things that people don't realize is that less is more when you're working with bonsai. The spaces in-between are just as important as the branches. And that's what you're doing all through the years, is you're just creating this image of this tree, and it keeps changing on you and you keep adding elements and taking away elements as it grows. When you do initially design the art piece, you do have some image in mind that you want to head toward. Typically, you do choose how high to want to make the tree. And you consistently prune it to keep it at that height. One of the really nice things I like about a bonsai is, I consider it an egoless art. If the hand of the artist shows, it's not good, it's just not good art. This is a collaborative type effort. It's not a painting that hangs on the wall. This is an art that you get involved in. It brings you back into nature. I sort of saw this image; I've been working toward it with this tree. It's choosing to grow this way, and I wanted it to grow that way. So I'm going to have to change my idea and create something that looks attractive and pleasing according to what the tree wants to do. I have to listen to the tree; the tree doesn't have to listen to me. The history of milling in rural Minnesota is embodied in the story of Phelps Mill. The historic flour mill near Fergus Falls, Minnesota, allows visitors to view the operation of a flour mill as it was in the old days. (man) What make Phelps Mill so unusual, is that the structure is basically intact. The way you see it is the way it looked when it was built in 1889 and the addition put on a few years later. The vast majority of the original machinery is still intact. I mean, you go into the Phelps Mill, it's like taking a step back in time. The owner of Phelps Mill, a man named William Thomas, he came from Bloomington, Wisconsin to work in the flour and feed business, and he worked in Fergus Falls until he purchased some acreage in Maine Township along the Otter Tail River. And he saw the rolling water, decided this would be a good place to construct a flour mill, which of course, he began doing in 1885, and it opened in December of 1889. The name Phelps Mill comes from Ray Thomas' wife, Leona Phelps; her maiden name was Phelps. So the town was called Phelps. The historic name of the mill when he opened it was the Maine Roller Mills. Maine for the township that we are in right now, and Roller Mills for the technology, the roller milling process. The mill was designed to produce 60 to 75 barrels of flour a day. Farmers from throughout the area would come with their wagons of wheat and it got to the point where so many farmers would come to bring their wheat that they would have to wait, and so he built a bunkhouse, called "The Farmers' Roost," where people, farmers could spend the night while waiting to get their wheat ground. And then a few years later, the mill expanded, and he built an addition, which is the red part of the mill, where the red tin siding is, and that was designed to grind buckwheat and rye. And the mill continued with great success through the early part of the 20th century, until it just became more and more difficult to compete with the great mills of Minneapolis and St. Paul, and it eventually closed. It was sold to a man in Underwood, H.G. Evenson in 1928 and he operated it for a few years doing some feed grinding, and then it permanently closed its doors in 1939. Milling is a complicated process, but through the machinery that is in Phelps Mill, you are able to follow how wheat was tuned into flour. Most rural flour mills, because of the dust of the milling process, had major fires and were burned to the ground. The fact that the Maine Roller Mill was able to survive those decades without a fire is totally amazing. The mill is wide open for the general public to walk around, so we are constantly worried about a stray cigarette coming, and the mill just going up in flames. We now have a security system in the mill, especially in the winter when it's shut up, so there's no break-ins. We recently installed lightening rods on the mill, thanks to a legacy amendment grant to protect against fire. We estimate at least 10,000 to 15,000 visitors come through during a season. The Phelps Mill Festival is held the second weekend of July. It's a major arts-and-crafts festival, benefits a lot of local organizations. and the reason it is so popular, in my opinion, is in the background you have the historic flour mill. It is a pretty easy drive from Minneapolis, from Fargo. It's just off Otter Tail County Highway 45. There's also the Phelps Mill store, which is the original general store and now they sell ice cream. A real popular place for people to visit. It just hearkens back to a rural lifestyle and a time that is long gone. You often hear that you are what you eat. Does it also matter when and where we eat and who we eat with? Next, we'll look at eating implications, a segment from the Prairie Public North Dakota Humanities Council project entitled, "Key Ingredients." The sitting down and eating together is as important to the health as the food itself. (man) From a spiritual understanding of our relationship with food, we have to first recognize that the fundamental understanding of what constitutes family is, who do you eat with? So from a spiritual respect, the understanding of how we are family, how we are community, comes through food. (all) Let this food to us be blessed. (Karl Limvere) We say Grace, or we give thanksgiving to God, 3 times a day, for our daily food. And so it's at our very base relationship with God being the food provider, the ultimate provider of our life, that what sustains us in life-- the connection is strong. (Wanda Agnew) We need to say thank-you at the table for our food and what the earth has provided us. There is a system in place. We come to the earth and we leave the earth at a certain time, and the decisions we make in-between those dates is really important, and food, we make food decisions at a minimum, 3 to 5 times a day. (man) Food and the gift of food had been extremely important to us as people. We grew up in a really poor household. Financially-wise, we had no money, but we were rich in the fact that we had our garden and when people came over, we fed 'em, and that was the custom in the old days. That's how you showed respect for your people, that's how you adopt your relatives as well, is the first thing you do is, you feed 'em, and you give 'em gifts. The garden is a huge part of our identity and always has been. Not only our identity, it's part of our spirituality, it's part of who we are as human beings, and so the foods were extremely well-respected, foods were alive, which you can hear from the women of our nation, is that they were considered the children, and especially when they start growing up in their garden, they would consider them children. They would sing lullabies they would pray, and they were taught. I can remember my mother doing that when I was a kid. We went out there and we were weeding the garden and she would be singing to them and talking to them. So those were very sacred items for us. Unfortunately, our modern society has broken down that relationship. Families don't eat together as they used to, fast food and convenience food has replaced that relationship that we've had in dining together, in spending time together, where the dining room table is a time when we reconstitute the family. We are a nation of overfed and undernourished people. Very undernourished, eating large quantities of factory or science-made food. If we're going to change, everybody talks about obesity. It's not an obesity issue epidemic, it's an epidemic of not having food traditions in our home. It's an epidemic of not eating smart and not moving more. (Karl Limvere) The food system needs to be a just system because it is very fundamental to the survival of humanity. And we're not creating that justice when someplace between 800,000 and a little over a billion people go hungry every night. It tells us that our food system does not serve humanity. My message is always that food is more than something to eat. Food impacts all of the components of our being, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. And if we want a strong society, a strong community, our public health message is plan your food, sit together, thank someone for the food, and use it as an opportunity to connect and bond with the people you care about. Minnesota State University Moorhead Professor and ceramic artist Brad Bachmeier uses a potter's wheel and the raku method of firing his pots to make remarkably beautiful and diverse-looking ceramic art. (Brad) The clay I'm using here is actually a commercially prepared clay that comes from Minnesota. I buy it from Minneapolis, and what I'm going to do first is, I'm going to wedge it-- so I opened a business, bought a potter's wheel and built a couple kilns, and started doing some local craft fairs and things. And from there, literally, I never would have saw it coming, but for the last 17 years, I've never been able to make enough work and keep up with demand from galleries and places, outlets that I've been selling. And that will prepare it so that it's ready to be thrown into a vessel on the wheel. The process that I use in firing is what probably sets my work apart from many other potters and makes it a little bit more rare, and that is, one style that I'm well-known for using, is the ancient form of raku, which is where you're firing pots to a red-hot temperature, around 2000 degrees, you're opening up the kiln, the pots are glowing red hot in there, and then you're pulling them out and immediately putting them in a reduction chamber. The other method that I use largely is pit firing, which is a very primitive method that was used since the very beginning of time by people all over the globe. And that is simply digging a hole in the ground and putting your pots in there and throwing whatever materials you've got, whether it's cow dung or whatever materials you've got available at hand to burn. And those pots maybe get up not quite 2,000 degrees, but hard enough, hot enough to fire those things and make them permanent. I'm going to begin by opening a hole in the center, and so I'm taking my thumbs and pressing a hole in. So when I ask this clay to stretch, it's going to stretch a long ways and hold itself out all the way out here. it takes a certain degree of, I suppose control, and it is a little bit more difficult method of throwing plates and platters, but again, it results in a nice elegant foot and nice light profile. Holding the needle tool still, and I'm going to cut off a little bit of that rim, just to ensure that it's nice and symmetrical all the way around. You know, I can take this, supporting it from underneath a little bit, and press down, and in one pass around the outside, create a nice even layer of marks. This piece is pulled out of the kiln at about 1200 degrees, and you actually lay strands of horse hair on it. They sizzle and burn into the surface, carbonize into the surface and leave nice fine black marks. I also laid some bailing twine across there, and that creates larger areas of smoke patterns. I think people are amazed when you say you're going into art, or that you sell pottery, and they assume that who in the Midwest would buy it, or that people around here wouldn't appreciate it, and it's quite the opposite. Again, over 17 years, I've just never been able to make enough. It's not been the problem of selling it, and it's not because it's more tremendous work than anyone else's. I think people underestimate the sophistication of people around here in recognizing and collecting pieces. In our next segment the Fargo-Moorhead Jazz Arts Big Band pays tribute to the classic sounds of Lawrence Welk and his orchestra. Led my Kyle Mack, the Jazz Band was formed in 1991 and is comprised of 18 members and a variety of guest vocalists. [Jazz Arts Big Band plays in bright rhythm] (Kyle) Here's Lawrence Welk's "Bubbles in the Wine." [playing in bouncy 2-step rhythm] [music only; no vocals] (Kyle) Next is "This Old House," featuring Merrill Piepkorn. [playing a syncopated intro] [in deep bass voice] This old house once knew my children This old house once knew my wife This old house was home and comfort As we fought the storms of life This old house once rang with laughter This old house heard many shouts Now she trembles in the darkness When the lightnin' walks about Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer Ain't a-gonna need this house no more Ain't got time to fix the shingles Ain't got time to fix the floor Ain't got time to oil the hinges Nor to mend that window pane Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer I'm getting' ready to meet the saints Well this old house is getting' shaky This old house is getting' old This old house lets in the rain And this old house lets in the cold On my knees I'm getting' chilly But I feel no fear nor pain I see an angel peekin' through That broken window pane Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer Ain't a-gonna need this house no more Ain't got time to fix the shingles Ain't got time to fix the floor Ain't got time to oil the hinges Nor to mend that window pane Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer I'm getting' ready to meet the saints Well, this old house is afraid of thunder This old house is afraid of storms This old house just groans and trembles When the night wind flings her arms This house is getting' feeble This old house is needin' paint Just like me it's tuckered out And I'm-a getting' ready to meet the saints Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer Ain't a-gonna need this house no more Ain't got time to fix the shingles Ain't got time to fix the door Ain't got time to oil the hinges Nor to mend the window pane Ain't a-gonna need this house no longer I'm getting' ready to meet the saints (Kyle) Here's a Cole Porter tune made famous by Artie Shaw, "Begin the Beguine." [playing rhythmic swing] [music only; no vocals] [electric piano solo] [full band] [electric piano solo] [horns take the lead] [piano takes the lead] Thank you for joining us for this edition of "Prairie Mosaic." If you know of an artist, a topic, or an organization in our region that you think might make an interesting segment, please contact us at... For "Prairie Mosaic," I'm Bob Dambach. (woman) "Prairie mosaic" is funded by-- the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund, with money from the vote of the people of Minnesota on Nov. 4th, 2008; the North Dakota Humanities Council, a nonprofit independent state partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities; the North Dakota Council on the Arts, and by the members of Prairie Public.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the township has a total area of 112.9 square miles (292.4 km2), of which 112.8 square miles (292.2 km2) is land and 0.1 square mile (0.2 km2) (0.07%) is water.

History

Originally established as three separate townships of Dosey (organized 1909), Keene (organized 1920) and Belden (organized 1921), the three townships merged in 1949 to form New Dosey.

Demographics

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 74 people, 38 households, and 22 families residing in the township. The population density was 0.7 people per square mile (0.3/km2). There were 212 housing units at an average density of 1.9/sq mi (0.7/km2). The racial makeup of the township was 91.89% White, 1.35% Native American, 2.70% Asian, 2.70% from other races, and 1.35% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.70% of the population.

There were 38 households, out of which 13.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.3% were married couples living together, 5.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.5% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.95 and the average family size was 2.43.

In the township the population was spread out, with 14.9% under the age of 18, 2.7% from 18 to 24, 12.2% from 25 to 44, 39.2% from 45 to 64, and 31.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 56 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.0 males.

The median income for a household in the township was $24,500, and the median income for a family was $55,625. Males had a median income of $0 versus $29,167 for females. The per capita income for the township was $24,298. There were no families and 7.1% of the population living below the poverty line, including no under eighteens and 25.0% of those over 64.

References

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.