Campo (second from left) and Flores (third from right) following their arrest. | |

| Date | 10 November 2015 |

|---|---|

| Location | Port-au-Prince, Haiti |

| Suspects | Efraín Antonio Campo Flores, Francisco Flores, Roberto de Jesus Soto Garcia and others. |

The Narcosobrinos affair (Spanish for drug-nephews) is the situation of events that surrounded two nephews of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores who were arrested for narcotics trafficking. The nephews, Efraín Antonio Campo Flores and Francisco Flores de Freitas, were arrested on 10 November 2015 by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration in Port-au-Prince, Haiti after attempting to transport 800 kilograms of cocaine into the United States.[1][2] A year later on 18 November 2016, the two nephews were found guilty, with the cash allegedly destined to "help their family stay in power".[3] On 14 December 2017, the two were sentenced to 18 years of imprisonment.[4]

In October 2022 Campos and Flores were released and sent to Venezuela as a prisoner swap reached with United States in exchange of five Venezuelan-American directors of the oil refinery corporation CITGO (part of the Citgo Six) imprisoned in Venezuela.[5]

Etymology

The word Narcosobrinos is the word narco, meaning "drug dealer", followed by sobrinos, which translates to "nephews". Its translation could therefore be "drug dealer nephews". The term derived from the media which focused on the relation of drug dealing charges to President Maduro's nephews.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Background

According to Jackson Diehl, Deputy Editorial Page Editor of The Washington Post, the Bolivarian government of Venezuela shelters "one of the world's biggest drug cartels". There have been allegations of former president Hugo Chávez being involved with drug trafficking.[12] In May 2015, The Wall Street Journal reported from United States officials that drug trafficking in Venezuela increased significantly with Colombian drug traffickers moving from Colombia to Venezuela due to pressure from law enforcement.[13] One United States Department of Justice official described the higher ranks of the Venezuelan government and military as "a criminal organization", with high ranking Venezuelan officials being accused of drug trafficking.[13] Those involved with investigations stated that Venezuelan government defectors and former traffickers had given information to investigators and that details of those involved in government drug trafficking were increasing.[13] Anti-drug authorities have also accused some Venezuelan officials of working with Mexican drug cartels.[14]

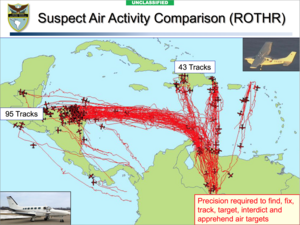

At a presentation at the XXXII International Conference on Drugs in 2015, commander of the United States Southern Command General John Kelly stated that though relations with other Latin American nations countering drug trafficking has been good, Venezuela was not as cooperative and that "there's a lot of cocaine leaving Venezuela to the world market". General Kelly also stated that almost all shipments of cocaine using aircraft comes out of Venezuela and that since 2013 to early-2014, the route of drug trafficking aircraft has changed from heading to Central America to primarily traveling through Caribbean islands.[15] The Narcosobrinos incident happened at a time when multiple high-ranking members of the Venezuelan government were being investigated for their involvement of drug trafficking,[16] including Walter Jacobo Gavidia, Cilia Flores' son who is a Caracas judge, former National Assembly President Diosdado Cabello, and Governor of Aragua State Tarek El Aissami.[17]

Series of events

Preparation and DEA monitoring

Campo Flores and Flores de Freitas were involved in illicit activities such as drug trafficking and possibly financially assisted President Maduro's presidential campaign in the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election and potentially for the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections.[17][18] One informant stated that the two would often fly out of Terminal 4 of Simon Bolivar Airport, a terminal reserved for the president.[17][18]

Source: United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

The nephews and DEA informants met on multiple occasions in Haiti, Honduras and Venezuela while every meeting "produced an audio recording plus three to seven videos".[19] Campo and Flores planned to ship cocaine supplied by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) to the United States and sought for assistance with their plans.[20] On 3 October 2015, a confidential DEA informant known as CW-1 and his employee "El Flaco" were contacted by a Venezuelan contact known as "Hamudi" who introduced Campo and Flores to the informant.[21][22]

The next day on 4 October 2015, the two flew from Venezuela to San Pedro Sula, Honduras, with nephews stating that they would use their connections to send narcotics on legal flights from Caracas, Venezuela to Roatán, Honduras, knowing that their relation to the president "would open doors for the smuggling operation".[2][19]

In late-October, CS-1, who presented himself as a Mexican drug boss and CS-2, presenting himself as an associate of CS-1, flew to Caracas, Venezuela to meet with the nephews.[2] Around 23 October 2015, CS-1 and CS-2 met with the nephews, with Campo stating that he was "the one in charge" and that "we're at war with the United States ... with Colombia ... with the opposition".[2] Campo also reassured the two informants that the cocaine shipments would not be tracked by law enforcement because the plane would "depart from here as if ... some from our family were on the plane".[2] Days later on 26 October 2015, Campo stated that the two were to ship cocaine and were seeking to raise about $20 million, explaining that CW-1 would be paid about $900,000 to receive the cocaine in Honduras.[2] The next day on 27 October 2015, Campo and Flores presented a kilogram of cocaine to CS-1 and CS-2 to show its purity, with the informants believing that the purity was between 95%-97%.[2] On 5 November 2015, informant CS-3 met with co-defendant Roberto de Jesus Soto Garcia to plan on how to receive the cocaine in Honduras.[2] Soto explained the schedule at the Juan Manuel Gálvez International Airport in Roatán, Honduras and stated that the load of cocaine would then be "arranged with all of those inside of the airport".[2]

Arrests

Campo Flores and Flores de Freites

On 10 November 2015, Campo Flores and Flores de Freites were flown into Port-au-Prince, Haiti by two Venezuelan military personnel accompanied by two presidential honor guards carrying more than 800 kilograms of cocaine destined for New York City.[19][1][16][23][24] The jet was a Cessna Citation 500 that belonged to Lebanese Venezuelan businessmen Majed and Khaled Khalil Majzoun, who were linked to old projects of the Hugo Chávez government and close to high ranking Venezuelan politician Diosdado Cabello.[25] CS-1 met with the nephews at a restaurant of a hotel near Toussaint Louverture International Airport and was supposed to pay them $5 million for the cocaine.[2][19] CS-1 then left into the bathroom and the Haitian Brigade de Lutte contre le Trafic de Stupéfiants (BLTS) and DEA agents raided the restaurant after identifying themselves, apprehending the nephews.[2][19] The BLTS personnel wore fatigues and vests that read "POLICE" so they would be able to be identified as well.[2] Campos and Flores were later turned over to the DEA and read their Miranda rights after boarding the DEA plane, being flown directly to Westchester County Airport in White Plains, New York in order to face an immediate trial.[2][19][16][23][24]

The two were interviewed separately on the DEA plane.[19] Campo stated on the DEA plane that he was the adopted step son of President Maduro and that he grew up in the Maduro household while being raised by Flores.[16][24] He was also shown a picture of a man with a kilo package of cocaine replying "That's me" and when asked what was in the package he said "You know what it is".[19] The two men possessed Venezuelan diplomatic passports but did not have diplomatic immunity according to former head of DEA international operations Michael Vigil.[18][23] A later raid of Efraín Antonio Campo Flores' "Casa de Campo" mansion and yacht in the Dominican Republic revealed an additional 280 lbs of cocaine and 22 lbs of heroin, with 176 lbs of the drugs found in the home while the remainder was discovered in his yacht.[26]

Due to the extradition process, New York courts could not apprehend those who assisted the nephews on their way to Haiti,[18] though a pilot was later arrested. It was also stated by those close to the case that there are more sealed warrants linked to the incident.[27]

Roberto de Jesús Soto García

On 28 October 2016, a Honduran man, Roberto de Jesús Soto García, was arrested in Honduras and extradited to the United States. According to authorities, Soto García was responsible for transporting drug shipments from Juan Manuel Gálvez International Airport. Soto García provided information about the port and was supposed to take the drugs from the nephews into the United States.[28]

Aircraft pilot

In June 2016, Yazenky Antonio Lamas Rondón, the pilot of the plane which transported the cocaine and the two nephews, was arrested at the El Dorado International Airport in Bogota, Colombia after the DEA and Interpol put out a warrant for his arrest. According to the DEA, Lamas Rondón piloted over 100 flights over the span of a decade from Venezuela which trafficked various drugs throughout Latin America. He is also believed to be involved with the Cartel of the Suns, a group of corrupt drug trafficking Venezuelan officials.[29]

Trial

The nephews originally plead not guilty to the charges of conspiring to transport cocaine into the United States,[30] with the two facing up to life in prison.[31] In trial papers filed on 1 July 2016, the nephews stated that they were not informed of their rights when detained, attempting to suppress their statements that they made to DEA agents after their arrest.[31] However, on 22 July 2016, their statements made to DEA agents were filed as exhibit by the United States Attorney Office in Manhattan, with the two men confessing to their conspiracy to traffic cocaine into the United States that was supposed to be supplied by the Colombian guerilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).[20] The pair hoped to make $20 million through multiple drug shipments.[20] A confidential informant posing as a leader of the Sinaloa cartel confessions testified that Efrain Campo planned to finance Cilia Flores' congressional campaign.[32]

On 18 November 2016, the jury reached a verdict finding the two nephews guilty of attempting to traffic drugs into the United States.[3]

Murdered informants

Two informants that observed the nephews were murdered shortly before and after their arrest, raising concerns that the drug trafficking operation was larger than suspected.[21] Two weeks before the nephews were arrested, the Venezuelan known as "Hamudi" who introduced the nephews to CW-1 was murdered by FARC suppliers.[21] Weeks after the arrests in December 2015, CW-1 was murdered as well.[21]

It is thought to be that the nephews were not "the brains" of the trafficking attempt but were working under the Cartel of the Suns. The murdering of informants was a possible way to cover possible involvement by Venezuelan officials. In the United States, the punishment for killing a witness is a federal offense punishable by up to life in prison or execution.[21]

Prisoner exchange

In October 2022 Campos and Flores were released and sent to Venezuela as a settlement reached with the USA government in exchange of five Venezuelan-American directors of the oil refinery corporation CITGO (part of the Citgo Six), who were held in prison in Venezuela, accused of signing an agreement that was "unfavorable" for the Venezuelan subsidiary.[5]

Media coverage

International media focused on the events surrounding the nephews and their trial while Venezuelan media was largely censored from revealing that the two were related to the President Maduro and his wife.[33] Venezuelan media organizations like Globovisión and Últimas Noticias only mentioned that "two Venezuelans" were charged with drug trafficking without showing any relation to the president's family, raising accusations of self-censorship.[34][35] Social media, which is popular in Venezuela, was used by journalists as a way to allow Venezuelans to bypass censorship and provide updates about the situation surrounding the president's nephews.[33]

Reactions

Academics and scholars

According to drug trafficking expert, Bruce Bagley of the University of Miami, "The nephews are just the tip of the iceberg ... Corruption is rampant in power circles in Venezuela. This case suggests a culture that drug trafficking is routine and daily fare for someone with contacts in the presidential palace", with Bagley further stating that "With their connections, they felt they would skate through ... They made a mistake because when the DEA heard their names they targeted them."[36]

Government of Venezuela

After Maduro's nephews were apprehended by the DEA for the illegal distribution of cocaine on 10 November 2015, Maduro posted a statement on Twitter criticizing "attacks and imperialist ambushes" which was viewed by many media outlets as being directed towards the United States.[37][38] President Maduro's wife, Cilia Flores, accused the United States of kidnapping her nephews and said that she had proof that they were kidnapped by the DEA.[39] Diosdado Cabello, a senior official in Maduro's government who has been accused of drug trafficking himself, was also quoted as saying the arrests were a "kidnapping" by the United States.[40]

Roberto de Jesús Soto Garcia, a Honduran man who provided assistance to the smugglers, has been linked to Venezuela's Vice President Tareck El Aissami.[41]

Following the arrest of the nephews, Associated Press correspondent Hannah Dreier was detained by SEBIN agents. She was then interrogated, being threatened with being beheaded in a way like ISIL did to James Foley, saying they would release her for a kiss. They later stated that they wanted to exchange Dreier for President Maduro's nephews.[42]

See also

References

- ^ a b Kay Guerrero and Claudia Dominguez (12 November 2015). "U.S. agents arrest members of Venezuelan President's family in Haiti". CNN.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bharara, Preet (22 July 2016). United States of America v. Efraín Antonio Campo Flores, and Franqui Francisco Flores de Freitas, S2 15 Cr. 765 (PAC). New York, New York: United States District Court Southern District of New York. pp. 1–78.

- ^ a b Raymond, Nate (19 November 2016). "Venezuelan first lady's nephews convicted in U.S. drug trial". Reuters. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "Nephews of Venezuela's first lady sentenced to prison for cocaine plot". The Guardian. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ a b BBC (October 2022). "US frees President Maduro's relatives in Venezuela prisoner swap". BBC News.

- ^ "Narcosobrinos Archivo". La Patilla. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "EEUU: postergaron una vez más la audiencia de los narcosobrinos de Maduro | Nicolás Maduro, Narcotráfico en Venezuela, Nueva York - América". Infobae. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Restan días para el juicio de los "narcosobrinos"". Venezuela al Día. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Carrillo Mazzali, Jessica. "Difieren audiencia del caso de los "narcosobrinos" de Cilia". Tal Cual. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "La mujer de Maduro acusa a la DEA de secuestrar a sus "narcosobrinos"". ABC (in European Spanish). 13 January 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Lozano, Daniel (17 November 2015). "Nicolás Maduro, seis días de silencio en torno al escándalo de los 'narcosobrinos'". El Mundo. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Diehl, Jackson (29 May 2015). "A drug cartel's power in Venezuela". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ a b c DeCórdoba, José; Forero, Juan (18 May 2015). "Venezuelan Officials Suspected of Turning Country into Global Cocaine Hub; U.S. probe targets No. 2 official Diosdado Cabello, several others, on suspicion of drug trafficking and money laundering". Dow Jones & Company, Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Meza, Alfredo (26 September 2013). "Corrupt military officials helping Venezuela drug trade flourish". El Pais. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "'Quisiéramos más cooperación del lado venezolano': EE. UU". El Tiempo. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d de Córdoba, José (11 November 2015). "U.S. Arrests Two Relatives of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on Drug-Trafficking Charges". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Yagoub, Mimi (20 November 2015). "Venezuela Military Officials Piloted Drug Plane". InSight Crime. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Blasco, Emili J. (19 November 2015). "La Casa Militar de Maduro custodió el traslado de droga de sus sobrinos". ABC. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Calzadilla, Tamoa (23 July 2016). "It took the DEA 37 days to bust Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro's nephews". Univision. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Venezuela first lady's nephews confessed to drug scheme, U.S. says". Reuters. 24 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e LaSusa, Mike (29 July 2016). "Witness Killings Deepen Mystery in Venezuela 'Narco Nephews' Case". InsightCrime. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Mataron en Honduras después del arresto de narcosobrinos a testigo cooperante de la DEA – LaPatilla.com". La Patilla. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Goodman, Joshua; Caldwell, Alicia A.; Sanchez, Fabiola (11 November 2015). "Nephews of Venezuelan First Lady Arrested on US Drug Charges". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Llorente, Elizabeth; Llenas, Bryan (11 November 2015). "Relatives of Venezuelan president arrested trying to smuggle nearly 1 ton of drugs into U.S." Fox News Latino. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "La Casa Militar venezolana custodió el viaje de la droga de los sobrinos de Nicolás Maduro - América". Infobae. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ "Dominican police raid mansion, yacht of Venezuelan president's kin, find 280lb of cocaine". Fox New Latino. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Delgado, Antonio Maria (18 November 2015). "Hijo de primera dama de Venezuela también es investigado por narcotráfico". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Detienen a hondureño con petición de extradición de EUA". La Prensa (in Spanish). 28 October 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Gagne, David (15 June 2016). "Venezuela Pilot's Arrest May Hold Clues to Cartel of the Suns". InsightCrime. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Córdoba, Nicole Hong And José De (18 December 2015). "Relatives of Venezuelan President Plead Not Guilty to Drug Charges". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b York, Reuters in New (5 July 2016). "Nephews of Venezuela's first lady thought cocaine arrest was kidnapping". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite news}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ "DEA: Nephew sold drugs to fund Venezuelan first lady's campaign". Miami Herald. Miami Herald. 16 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ a b Petit, Maibort (19 November 2016). "El día del veredicto: Los narcosobrinos tuvieron que asumir la responsabilidad por sus delitos". La Patilla. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "Corte Federal de EEUU declara culpable a venezolanos por ingresar droga al país". Globovisión. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "La burda manera en la que Globovisión y UN "informaron" sobre veredicto de narcosobrinos". DolarToday. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Adams, David (25 July 2016). "Venezuela drug case reveals 'rampant' culture of corruption in circles of power". Univision. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "What's Wrong with Venezuela?". International Policy Digest. 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "U.S. arrests Nicolas Maduro's family members – CNN.com". CNN. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "Venezuela's first lady Cilia Flores: US kidnapped my nephews over drug charges". The Guardian. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Kurmanaev, Anatoly. "Arrest of Nicolas Maduro Relatives a 'Kidnapping,' Venezuelan Official Says". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Maria Delgado, Antonio (29 June 2016). "Presentan cargos por narcotráfico contra socio hondureño de los sobrinos de Maduro". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Departing AP reporter looks back at Venezuela's slide". The Washington Post. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

External links

Media related to Narcosobrinos incident at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Narcosobrinos incident at Wikimedia Commons