| Nambikwaran | |

|---|---|

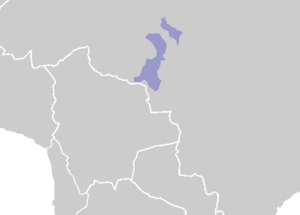

| Geographic distribution | Mato Grosso, Rondônia and Pará, in Brazil |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | namb1299 |

| |

The Nambikwaran languages are a language family of half a dozen languages, all spoken in the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil. They have traditionally been considered dialects of a single language, but at least three of them are mutually unintelligible.

- Mamaindê (250-340)

- Nambikwara (720)

- Sabanê (3)

The varieties of Mamaindê are often seen as dialects of a single language but are treated as separate Northern Nambikwaran languages by Ethnologue. Sabanê is a single speech community and thus has no dialects, while the Nambikwara language has been described as having eleven.[1]

The total number of speakers is estimated to be about 1,000, with Nambikwara proper being 80% of that number.[2] Most Nambikwara are monolingual but some young men speak Portuguese.[3] Especially the men of the Sabanê group are trilingual, speaking both Portuguese and Mamainde.[4]

Genetic relations

Price (1978) proposes a relationship with Kanoê (Kapixaná), but this connection is not widely accepted.[5]

Language contact

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Aikanã, Irantxe, Itonama, Kanoe, Kwaza, Peba-Yagua, Arawak, Bororo, and Karib language families due to contact.[6]

Varieties

Jolkesky (2016)

Internal classification by Jolkesky (2016):[6]

(† = extinct)

Loukotka (1968)

Below is a full list of Nambikwaran language varieties listed by Loukotka (1968), including names of unattested varieties.[7]

- Nambikwaran

- Eastern dialects

- Tagnaní - spoken on the Castanho River (Roosevelt River), Mato Grosso.

- Tamaindé - spoken on the Papagaio River and Marquez de Sousa River, state of Mato Grosso.

- Neneː - spoken at the confluence of the Juína River and Juruena River, Mato Grosso.

- Tarunde - spoken in the same region on the 12 de Outubro River.

- Central dialects

- Kokozú / Uaindze / Ualíxere - spoken on the left bank of the 12 de Outubro River.

- Anunze / Soálesu - spoken between the Papagaio River and Camararé River, Mato Grosso.

- Kongoreː - spoken on the Buriti River, Mato Grosso.

- Navaite - spoken on the Dúvida River, Mato Grosso. (Unattested)

- Taduté - spoken by the neighbors of the Navaite tribe on the Dúvida River.

- Western dialects

- Tauité / Tawite - spoken on the Camararé River, state of Mato Grosso.

- Uaintasú / Waintazú - spoken in Mato Grosso on the right bank of the Pimenta Bueno River. (Unattested)

- Mamaindé - spoken on the Cabixi River, state of Mato Grosso. (Unattested)

- Uamandiri - spoken between the Cabixi River and Corumbiara River. (Unattested)

- Tauandé - spoken on the São Francisco Bueno River, Mato Grosso. (Unattested)

- Malondeː - spoken in the same region but exact location unknown. (Unattested)

- Unetundeː - spoken on the upper course of the Dúvida River. (Unattested)

- Tapóya - language of the same region, exact location unknown. (Unattested)

- Northern dialects

- Sabané - spoken on the Ananáz River (now the Tenente Marques River) and Juína-Mirim River, state of Mato Grosso.

- Jaiá - spoken on the Ananáz River (now the Tenente Marques River). (Unattested)

- Lacondeː - spoken on the right bank of the Castanho River (Roosevelt River). (Unattested)

- Eastern dialects

Mason (1950) lists the following varieties under "Nambicuara proper":[8]

Mason (1950)

- Nambikwaran

- Northeastern

- Eastern: Cocozu

- Northeastern: Anunzé

- Southwestern

- Western: Tamaindé

- Central and Southern

- Uaintazu

- Kabishi

- Tagnani

- Tauité

- Taruté

- Tashuité

- Northeastern

Sabane is listed by Mason (1950) as "Pseudo-Nambicuara" (Northern).

Vocabulary

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for various Nambikwaran languages.[7]

| gloss | Tauité | Sabané | Anunze | Elotasu | Kokozú | Tagnaní | Tamaindé | Nene | Tarundé |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | améro | knakná | kenáge | etegenõ | ganagidzyare | banuré | kanákero | ||

| two | baléne | haːro | searu | dehaunõ | bandyere | lauré | baʔãdo | ||

| head | ua-negetü | dwa-haniːkin | toa-nekisú | ga-nakitú | nuhi-naite | nu-naite | |||

| tongue | tayú-hendü | uai-lehrú | año-heru | toái-herú | uai-hendé | noio-hidnde | nuiú-endé | nui-edende | |

| hand | toái-kizeː | depibá | uai-kizé | dwa-hikisu | toái-ikisú | ua-hité | nuhiː-hĩte | nuna-noré | |

| woman | akiːnaʔñazé | dusé | dosú | temoreː | ndenore | tenoré | denõ | ||

| water | ari | uarazé | iñausu | unsazú | narutundú | nahirinde | narundé | náru | |

| sun | utianezeː | yóta | ikidazé | udiʔenikisu | uterikisú | chondí | nahnde | naneré | |

| maize | guyakizeː | kayátsu | kayátsu | giaté | kaiate | kiakinindé | kiáteninde | ||

| parrot | anʔanzí | kakaitezé | ãhru | áhlu | aundaré | aúndere | |||

| bow | arankizeː | ukizé | úkisu | hukisú | huté | hute | aindé | ||

| white | eːseːnanzeː | pãte | kuidisú | han | ahéndesu | déʔende | hanidzare | haniʔna |

Proto-language

| Proto-Nambikwaran | |

|---|---|

| Proto-Nambiquara | |

| Reconstruction of | Nambikwaran languages |

Proto-Nambiquara reconstructions by Price (1978):[9]

Proto-Nambiquara reconstructions by Price (1978)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bibliography

- Costa, Januacele Francisca da; W. Leo M. Wetzels. 2008. Proto-Nambikwara Sound Structure. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Araujo, G. A. (2004). A Grammar of Sabanê: A Nambikwaran Language. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. 94. Utrecht: LOT.

- Gomes, M. A. C. F. (1991). Dicionário Mamaindé-Português/Português-Mamaindé. Cuiabá: SIL.

- Kroeker, M. H. (1996). Dicionário escolar bilingüe Nambikuara-Português, Português-Nambikuara. Porto Velho: SIL.

- Price, D. P. (1978). The Nambiquara Linguistic Family. Anthropological Linguistics 20:14-37.

References

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- ^ Nambiquaran languages. Ethnologue. Retrieved on 2012-07-29.

- ^ Kroeker, 2001 p. 1

- ^ Ethnologue. Ethnologue. Retrieved on 2012-07-29.

- ^ Price, David P. 1978. The Nambiquara linguistic family. Anthropological Linguistics 20 (1): 14–37.

- ^ a b Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho De Valhery. 2016. Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Brasília.

- ^ a b Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- ^ Mason, John Alden (1950). "The languages of South America". In Steward, Julian (ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 6. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 143. pp. 157–317.

- ^ Price, D. (1978). The Nambiquara Linguistic Family. In Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 14-37. Published by: Trustees of Indiana University. Accessed from DiACL, 9 February 2020.