Gosper County Courthouse | |

| |

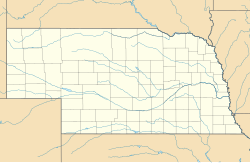

| Location | 507 Smith Ave., Elwood, Nebraska |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°35′16″N 99°51′38″W / 40.58778°N 99.86056°W |

| Area | 1.1 acres (0.45 ha) |

| Built | 1939 |

| Architect | McClure & Walker |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| MPS | County Courthouses of Nebraska MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 90000961[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 5, 1990 |

The Gosper County Courthouse, at 507 Smith Ave. in Elwood, Nebraska, was built in 1939. It was designed by architects McClure & Walker with Art Deco style.[1]

It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.[1] It was deemed historically significant for its architecture and for its association with politics and local government; it was one of seven Nebraska courthouses built by New Deal programs.[2]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/2Views:2 97413 525

-

The Lincoln Lectures — Lincoln At The Gates of History

-

How To Become a Phlebotomist - From Phlebotomy Training to Certification

Transcription

Trevor Plante: Good afternoon, and thank you for joining us today. My name is Trevor Plante. I'm an archivist in the old military reference section. Today it is our pleasure to welcome Charles Bracelen Flood to the National Archives. The author of twelve books including historical works ranging from the Revolutionary War to Adolf Hitler. His Civil War titles include "Lee: The Last Years" and "Grant and Sherman: The Friendship That Won the Civil War" Today we gather to hear more about his latest book, "1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History". 2009 is really the year of Lincoln. As we celebrate the anniversary of the birth of the 16th president, there is an abundance of lectures, symposia, and books focused on Abraham Lincoln. The author we have with us today has chosen to focus on another year of Lincoln, that of 1864. A year Lincoln entered with, and this is a quote from his book, "Everything bearing down on him. The war itself, the rapidly eroding public support for the war, the passionate political opposition he and his administration inspired, and the struggle to win a second term. So what happens in 1864? Ulysses S. Grant is brought east to replace Henry Halleck as General-in-Chief of all the Union armies. Grant soon accompanies the Army of the Potomac on what would become the Overland Campaign with fighting from the Wilderness to the siege of Petersburg. In the summer, Confederate General Jubal Early's raid on Washington sends a scare into the Union capital. Lincoln himself will proceed to the front and see things at Fort Stevens, one of the forts surrounding part of the defenses of Washington. Soon will follow the Valley Campaign, and the nation will learn more about Philip Sheridan. All the while, Union General William T. Sherman is working his way towards Atlanta. And after capturing that city will proceed on his famous march to the sea. On the political front, Lincoln is worried that he might not win the presidential election in the fall, as he's facing growing opposition from both the Copperheads and Radical Republicans. As I was reading the author's description of Lincoln dealing with Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout in Maryland, one of the passages that struck me was his line, "Here was Lincoln waging both war and peace." I won't ruin the end by revealing the end of the book, but to talk to us more about that pivotal year of 1864, ladies and gentlemen, Charles Bracelen Flood. Charles Flood: Thank you very much. Trevor Plante: One last comment. When we go to the questions and answers after Mr. Flood is finished, if you have questions we have microphones at the bottom of the stairs on each side. Please utilize those so everyone can hear your question. Charles Flood: Thank you, Trevor. Thank you for the introduction. I thank all of you for being here. I see a few familiar faces, including one from far out of my past who has quite distinguished connections with Washington. And I do want to express my own personal indebtedness to this institution. I have made use of it for decades, starting back in the mid-1970's when I came here and finally found deep in your place - In an office that didn't have walls. It sort of had what looked like a green painted chain link fence. And it was presided over by a marvelous man named Charles E. Taylor. Who was the guru of military history at this institution at the time - For some 30 or more years with its photographs or specific information, I have been one of the many, many people who is indebted to the National Archives. So without any - and I will say I love the questions and answers. And as far as I'm concerned, there are no dumb questions. And in audiences like this, I know there will be questions I can't answer. And I will do you the respectful thing and tell you that I do not know the answer. And with that I think we'll kick off. 1864 was the key year in Lincoln's life. The year that reveals his unique importance to our history. The year that revealed the meaning of his life. More than 1776, which is in my view it's only competition, 1864 was the most crucial year in American history. I begin my first chapter at the White House New Year's Day reception on January 1st, 1864. 8,000 people had lined up on the frozen lawns to come in and greet President Abraham Lincoln. He was standing in the East Room with his wife Mary beside him. To give you the essence of an undoubtedly complicated man, here is one simple, accurate eye-witness account of something that occurred. "The President had been standing for some time, bowing his acknowledgements to the thronging multitude, when his eyes fell upon a couple who had entered unobserved - A wounded soldier and his plainly-dressed mother. He made his way to where they stood. Taking each of them by the hand with a delicacy and cordiality that brought tears to many eyes, he assured them of his interest and welcome. Governors, senators, diplomats passed with merely a nod. But that pale young face he might never see again. To him, and to others like him, did the nation owe its life." The reason there are so many celebrations of Lincoln's 200th birthday this year is his remarkable combination of idealism, sensitivity, and shrewd practical political ability. This was coupled with his rock-like determination to preserve the Union. But at the time, the physical Lincoln made an enormous impression on everyone who came near him. Before dealing with 1864's great challenges and events, I will introduce you to the Abraham Lincoln his contemporaries knew. He stood 6'4" when the average Union soldier was 5'6". Lincoln was a man of great strength and stooped posture. He walked in an odd way. Lincoln moved the long legs of his lanky body in a full stride, walking quickly, but he put the soles of his feet down so flat with each step that he seemed to be stamping along. The harshest judgement on his appearance came from a fellow Republican, an Ohio newspaper editor who said, "His body seemed to me a huge skeleton in clothes." Those who knew Lincoln often described him as homely, but never as being ugly. At one point during his debates with Senator Stephen Douglas in 1858 that first brought him to the national attention, Douglas accused him of being "two-faced." Without missing a beat, Lincoln replied, "If I had two faces, do you think I'd be wearing this one?" As for Lincoln's use of the English language, it combined his unique eloquence with what came naturally to a man who spent his youth and young manhood on the Illinois and Indiana frontiers. Here was the man who could give his nation the Gettysburg Address, but greeted people with "howdy." Lincoln had a high-pitched voice. When he laughed, it reminded one listener of the name of a wild horse. He pronounced "chair" as "cheer". "Mr. Cheerman." The same vocabulary and style that enabled him to write the sublime Second Inaugural Address, "With malice toward none, with charity for all," alternated in his conversation with the rustic terms, "I reckon" and "By jinks." Rounding out the descriptions of Lincoln, he said what he called his coarse, black hair that always looked like a bird's nest. But one man saw this homespun genius through the prism of his own genius. Walt Whitman, who spent much of the war in Washington tending to the wounded, often watched Lincoln passing in a carriage. Their eyes sometimes met. Whitman had this reaction. "It is as if the earth looked at me. Dumb, yearning, relentless, immodest, inhuman." No account of Lincoln at this time can fail to mention his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. She was undoubtedly an erratic, neurotic woman. In recent years there have been efforts made by various writers to modify and improve her reputation. I am not one of those writers. Mary Lincoln had a tragic life, even before her husband was assassinated. But so did many women of her generation. In my book, I set forth examples of her behavior that led me to my largely negative assessment of her. And in my chapter notes I list some contemporary accounts of her activities. A particularly interesting collection of these is in a little-known work by the eminent Lincoln scholar Michael Burlingame. And it's titled "Honest Abe, Dishonest Mary". In a recent comment about her Burlingame, who clearly has not changed his mind, said, "Mary Todd Lincoln deserves to be pitied more than censured, but she behaved very badly indeed. Apart from more serious matters, she was a compulsive shopper. If you find yourself in a conversation about Mary with one of her revisionist supporters, you might try saying for openers, 'Well not every woman of her era bought 400 pairs of gloves in 3 months.'" On that New Year's Day of 1864, here is what some of what lay ahead for Abraham Lincoln in the 12 months to come: The Civil War had been going on for 33 months, on its way to being what is the bloodiest war in American history to date. In 1863 the Union army had won great victories at Vicksburg, Gettysburg, and Chattanooga. But as 1864 began, the Confederates still had the strength and leadership they had in 1863, giving them Chancellorsville and Chickamauga. Lincoln had not yet promoted Ulysses S. Grant to be his General-in-Chief. To this point, every commander of the Union army had underestimated southern determination. On this New Year's day of 1864, virtually every man of Robert E. Lee's still powerful Army of Northern Virginia was volunteering to reenlist for the duration of the war. To fight on, no matter how long that might take. And on this New Year's Day, right after leaving this reception and walking over to the telegraph office in the nearby War Department, Lincoln read an alarming telegraph. The Confederate General Jubal Early was reported to have moved more than 6,000 of his swift-striking forces into an area of Virginia and West Virginia 60 miles northwest of Washington. And I will underline, as I do in my own talk here, northwest of Washington. Early could begin talks there within 24 hours. Here you have both reality and symbolism. After 3 years of fighting, Lincoln's massive Union army could not capture the Confederate capital of Richmond 95 miles to the south, underlined, of Washington. But the Confederate army could still threaten places northwest of Washington. A word here about different war aims. No Confederate military or civilian leader had the remotest desire or need to try to march into New York or Boston or Chicago. In a sense, the Confederates had won all that they wished to win early in the war. They had what they wanted. An independent southern nation that intended to continue its practice of slavery. The Confederates had to do just two things. The first was to keep the territory they had. The second was to keep inflicting such horrendous casualties on the Union army that the northern public would in effect say, "Alright, you go your way and we'll go ours." By 1864, the north was becoming thoroughly sick of the war. The patriotic wife of a United States Navy captain wrote a friend, "We are panting for peace." In November of 1864 there would be a presidential election. It was going to be a referendum on the war. Here's the lineup. As what could be called the large core of the incumbent party, you had Lincoln and the moderate Republicans. They wanted victory, thus preserving the Union, and freedom for the 4 million slaves in the south. To his right were the Republicans known as Radicals, with a capital R. who in the event of victory wanted a harsh peace to be imposed on the South. The Radicals not only wanted the slaves to be free, but to be immediately given full civil rights including the vote. Many of the radicals also wanted the lands of slave-holding southerners to be confiscated. In addition, they intended to impose varying forms of punishment for Confederate military officers and civilian officials. This would include a ban on their ever again holding public office in a reunited country. Not without series opposition within the Republican / Radical spectrum, including an effort to become the Republican nominee made by his own Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln became the candidate of the Republican Party. For the 1864 campaign, the Republicans adopted in inclusive-sounding name, National Union Party. As big as the rift in the Republican's ranks was, there was a larger chasm among the Democrats. The majority of them were War Democrats, ready to continue the war for the purpose of preserving the Union. But they were much less interested in freeing the 4 million slaves in the South. The very vocal and potent minority on the Democratic side were the Peace Democrats. As their name indicates, they were ready to explore a negotiated peace that might well leave the Confederacy as an independent nation with slavery intact. This large faction was also known outside their own ranks as the Copperheads, snakes biting the Union in the back. Partly to protect themselves from being seen as active pacifists in the middle of a war, the Democratic Party as a whole chose as its candidate the Union General George McClellan. He had failed as a general and been sent home to New Jersey, but no one could call him a pacifist. There was yet another exceedingly important factor in play. And I have to say that a number of studies, I think, have not given this quite enough attention. That was the military vote. Effective plans were being made for what was to be by far the largest absentee balloting in our nation's history to that time. Here you had close to a million young men from families of different political persuasions. Many of these soldiers were being shot at every day. No one could be sure that they would vote to continue a war in which so many of their comrades were being killed and maimed. In hindsight, it's easy to say that of course Lincoln was reelected and the north won the war. But there were an endless number of times during 1864 when it did not look that way. When I mention what went on in terms of military action, please remember that military success or failure was inextricably linked with what would be Lincoln's political success or failure. Four days before the Baltimore political convention in early June that nominated Lincoln to run for a second term, Ulysses S. Grant presided over a military disaster. His forces had been taking terrible casualties as they moved south against Robert E. Lee through the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania. Now he started one of the largest attacks of the war at a place in Virginia called Cold Harbor. Grant had 108,000 men, and threw them straight at Lee, whose 59,000 men were well-entrenched. In the first hour, and some say even within the first 20 minutes, 7,000 of Grant's men were killed or wounded with the Union attack repulsed and nothing gained. Now there's some question whether the full impact of that disaster reached the Baltimore Convention, which in any case did nominate Lincoln. But the bad news went on for many more weeks. At one point, Grant had lost more than 40,000 men in 30 days. And that figure grew to his having lost 60,000 men in 45 days. 60,000 men dead and wounded to advance 60 miles. These were enormous figures compared to all that both sides had suffered before. By August, the Union losses for 1864 alone had reached 90,000 men. Also during that time, Jubal Early once again erupted from the Shenandoah Valley. He led a massive raid that brought a force of 12,000 men right to the edge of Washington's fortifications, five miles from the White House. Lincoln and Mary went out to Fort Stevens, the focal point of the attack. At one moment, the Confederate advance came to within 110 yards of the fort. Foolishly, Lincoln, wearing a stovepipe hat that made him a target 7 feet high, climbed right up on the parapet in the open. Some confederate snipers positioned a few hundred yards away started firing at him, missing him but wounding with a ricochet an officer who was standing just below the parapet. It's worth mentioning that this is the only time that an American president has been under enemy fire while serving in office. There are some fascinating eye witness accounts of this incident. The best comes from a sergeant of the 150th Ohio defending the fort, who later wrote, "Some of our boys who brought in prisoners said the captured men told them that Lincoln was seen, recognized, and fired at. When Lincoln was shot at, a 23-year-old colonel near him shouted, "Get down, you fool!" There's some question as to whether, in all the confusion, the young colonel knew that he was shouting at his Commander-in-Chief. But Lincoln knew who this officer was. He was Bostonian Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the future Great Supreme Court Justice who had been wounded three times earlier in the war. As Lincoln and Mary left the fort some time later, the President turned to Holmes and said, "Goodbye Colonel Holmes. I'm glad that you know how to talk to a civilian." All of this news - frightful Union casualties throughout northern Virginia and Confederates striking at the capital - was coupled with bad news from Georgia. As William Tecumseh Sherman slowly struggled towards Atlanta on the southern front, cutting into the Confederacy from its western side starting from Chattanooga, he was thrown back at Kennesaw Mountain in Georgia. That coincided with half-true rumors of peace feelers going back and forth between north and south. The northern public was increasingly confused and disappointed in Lincoln and his administration. Much of the press was coming out against Lincoln. Even his own advisers were warning him that, as one of them put it, "The tide is turning against us." The Union's economy was intertwined with all of this. Speculation in gold in New York City indicated fears that the north's financial structure might collapse. The national debt was at its highest. The public credit was at its lowest. and the treasury was running out of money paying for a war that appeared to be at a stalemate. In foreign business dealings involving evaluations of the dollar, it dropped to a new wartime low of 37 cents. Prosperous Republicans who wanted Lincoln to be reelected were nonetheless getting rid of greenbacks by buying land. They were doing that on the theory that land would still have value even if the Democrats were elected and decided to repudiate federal government securities right down to leaving the dollar worthless. And to underline that, the dollar bill then and now is a federal government security of a special type. So the idea was that they were worried that even a dollar might become worthless. On August 23rd, Lincoln involved himself in an extraordinary act that demonstrated his belief that he would lose the election. When the members of his cabinet assembled for one of their Tuesday afternoon meetings, they found Lincoln asking each of them to sign, without knowing what it said, the back of a folded over and sealed document. What Lincoln had written that morning, what they could not see, and what he was asking them to endure, sight unseen, by placing their signatures on it, was this statement: "This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly unlikely that this administration will be reelected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the president elect as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration." In other words, he was pledging himself and his cabinet to make an orderly transition to what he thought was going to be McClellan and a Democratic administration. So if anybody tells you that by 1864, Union victory or Lincoln's reelection was in the bag, I would respectfully refer them to Lincoln's own estimate of the situation. He remained determined to do everything he could. He backed Grant and his other generals to the hilt. But speaking to a Radical Republican, he told the man, "You think I don't know I am going to be beaten, but I do. And unless some great change takes place, badly beaten." A week after Lincoln said that, Sherman sent a telegram north that read, "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won." Everything changed. There it was. The news bringing the hope that so many in the north had lost. Even the most ardent Confederates saw this as the enormous strategic victory that the Union had won. Atlanta, the south's second most important city after Richmond, dead center in what had been Confederate territory, had fallen. There were still nine weeks until the election, but everything began to go Lincoln's way. He was reelected in an Electoral College landslide. Not so decisive in the popular vote, which came in with Lincoln winning by 400,000 out of 4 million cast. It's worth noting that in the military vote, ballots cast by soldiers who knew they were voting to continue risking their lives, he triumphed by 3 to 1. In the Shenandoah Valley, Lincoln's brilliant young cavalry general Philip Sheridan finally vanquished the tenacious Jubal Early. At Atlanta, the stage was set for Sherman's March to the Sea. And on Christmas Day of 1864, Lincoln read another telegram from Sherman which said, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns, plenty of ammunition, and also 25,000 bales of cotton." So as 1864 ended, the war was at last winding down. In 13 more weeks, Robert E. Lee would surrender to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse. 17 days after that, Lee's West Point classmate Joseph E. Johnston would surrender the Confederacy's other sizable forces to Sherman in North Carolina. Between those two surrenders, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln in Washington on April 14th, 1865. At the end of my book, I look ahead of those events of 1865. But my detailed treatment ends where it began, with the White House New Year's Day reception of 1865, a year after my opening scene. And here again is the essential Lincoln. The ultimate politician who nevertheless transcended the political strife. The indispensable man who appeared at our nation's convulsive hour. The resolute figure who proved that character is destiny. At this reception a nurse who served with the Union Army, Ada Smith, had come by herself to the White House to pass through the long receiving line and wish the President well. As she came through the door, she recognized a crippled lieutenant named Gosper who had lost a leg and was hobbling forward on crutches as he made his way to the East Room. In the fighting around Petersburg earlier in the year, Ada had been his nurse when he was brought in with his right leg shot off. They became friends from the time she cared for him. They greeted each other and joined the line of hundreds that wound around the East Room waiting to shake hands with Lincoln, who had Mary beside him. From where he stood, Lincoln saw Gosper. He broke away from his place and came striding from the other side of the big East Room to greet him. He took Gosper's hand, and in what Ada remembered as "a voice unforgettable," said, "God bless you, my boy." As they left, Gosper said to her, "I'd lose another leg for a man like that." So there is our Lincoln. Yours and mine. And some of the reasons that this year we've celebrated having him as our fellow American. Thank you very much. And now to the questions and answers. I'm eager. Yes mam, right there. Audience Member: I have a letter... Charles Flood: Now I can hear you, but there are these microphones. You needn't go now. Maybe we can do it without going to the microphones, but please be aware that they're there. Go ahead, please. Audience Member: I have letters that were written to my great grandmother, who lived in Howard County, Maryland, from Baltimore, from her sister. And after Lincoln was assassinated, he said they are searching for Mr. Booth house to house. And she was worried that they would find Booth in Baltimore. Can you give me some context to that? Charles Flood: Only that nobody knew where he'd gone. You know, nobody knew where he had gone. And the search eventually led south, but I can't give you any speculation. Baltimore certainly had been very much, originally, a Confederate - it was a Border State. A lot of Confederate sympathizers. Certainly a plausible place for a man in his situation to head. Actually quite an elaborate thing had been set up in advance to try to smuggle him down towards Richmond and so on. But I think I'll let that one go, at that. Because I have no special information on it. But thank you. Audience Member: He's buried in Baltimore. Charles Flood: Other questions, please? Yes sir, please. Audience Member: One of the What Ifs is that when the Union army first reached Petersburg, they still had the memory of Cold Harbor. But Petersburg in fact was virtually undefended. And so you could have a scenario where the Union army marches in and Richmond falls within a week. So I'm wondering what scenario - what would the 1864 campaign have been like if the war is over weeks before the election is held? Charles Flood: Well that's a very good question, but I'm not prepared to say that the war would have been over even if Richmond had fallen. Alright? It's fun to play What If, but we really don't know. Because still the Union army - I have no reason to think that Richmond falling would have automatically - by the time Richmond finally fell a year later, a great deal had happened. The Confederates had been greatly depleted in their forces, their strength. To some degree their willingness, although it was remarkable to fight on. So I'm not at all sure that the collapse of Petersburg and Richmond would have brought about that quick end to the war. So if I may I'll just leave that What If with my Maybe If. Anybody? Yes sir, please. Audience Member: In your research, have you come across anything about the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and Alexander Stephens when they were congressmen together before the war? Charles Flood: I'm aware of it. The next time he saw Stephens was at the Hampton Roads Conference, the peace conference that took place in early 1865. And Alexander Stephens, the Vice President of the Confederacy, was a very small man. But it was a cold day out on these ships on Hampton Roads, and he arrived with many coats, scarves, and so forth. And Lincoln good-naturedly said, based on their previous friendship - and it wasn't a cheerful relationship - As Stephens finally appeared as the little man he was, after taking off three coats and four scarves and so forth, he said, "I've never seen so big a husk produce such a small kernel." And they all - it was a very cheerful, civilized conversation. But it became - I'll just go on with that incident, and not back to Congress in 1848. There was a very civilized conversation, but it became clear that Jefferson Davis, who was not there and still back in Richmond, was not going to give way on either of the points. Whatever was concluded, he wanted the Confederacy to be an independent nation. And he wasn't prepared to give up on slavery. So within a pretty short time - they talked for about 4 hours, but within a very short time it became clear there was not much negotiating room. Because those were two things that Lincoln was not prepared to do. Interestingly enough, Lincoln had the idea of maybe, for $400 million dollars - which was a big sum in its day - to see if he could bribe the Confederacy, if he could buy the slaves. Maybe he could bring the war - that could be one of the tools. But when he floated that in front of his cabinet they said no. And he certainly wasn't going to go against his whole cabinet. But excellent question, and I wish I could take you back more to that particular time in Congress. But I had so much to look at in 1864, I didn't study him very intensively during his one rather undistinguished and seemingly unimportant term in Congress. So it took place in 1848-1850. Good question. Anybody else, please? Audience Member: Mr. Flood. I was wondering, would you mind elaborating on Lincoln's plans for Reconstruction? And did Johnson really follow those? Charles Flood: Let me back up a little bit. I think I'd rather go to a very broad-stroke thing and give you the spirit of it rather than the details of it. Because I'm not sure that he had really worked on nuts and bolts to that extent. He'd already been trying to bring states back into the Union as their territory fell. So we know that he wanted the country to be - he did not want it ever to be considered that the Confederacy was actually out of the Union. These states were in rebellion, but he never talked about the Confederacy as a separate nation, and so forth. So to that extent he was trying to bring them back in to what he called their "proper, practical relations" with the Union. Having said that, when he went down to Richmond - and I think it's almost like - who am I to say just what his state of mind was. But he went down to Richmond while the war was still on. Richmond had fallen. And he - I think it was almost a little boy element of it. He went into the Confederate White House and sat down in the chair at the desk of Jefferson Davis. And I think maybe there was a little moment of, "See? I'm here and you're fleeing somewhere south of here." And he also said - more importantly and getting to your point, as far as it goes philosophically - he said to the Union general who was in command of Richmond - but I think it was of much wider application - he was talking about the people of Richmond and the prisoners who had been caught right there. He said, "Let them up easy, general. Let them up easy." I think that very much would have been his policy. And I think he would have been able to make that stick, because he would have had the enormous prestige of being the reelected and victorious president. And would have had a mandate totally unlike that of Andrew Johnson. I think that's about all I could say on that. I would like to say, however - this morphs into something else about what his post-war plans were. And this is one of my two big surprises. And if somebody wants to ask me what the other surprise is, I'd be grateful to them. I did not realize that he had this vision - Very strong and well-articulated. And very well marked out by past legislation - for the post-war, unified United States. And he had been a lawyer for the Illinois Central Railroad before the war, which was the largest railroad in the world at the time. He always was thinking in terms of the westward expansion of the United States. And he put this in an almost seamless web. He had an act to encourage immigration. He had dovetailed that with the Homestead Act. So what you had was advertising in foreign countries aimed largely at farmers. Come to the United States, settle on 160 acres - ideally, from his point of view - west of the Mississippi. And if you're on it a certain length of time, that farm becomes yours. And during the war, 615,000 immigrants came here. And most of them settled west of the Mississippi according to plan. Also locked into that as a vision of a future nation was the Moral Act, which created the land-grant colleges and many of our famous state universities - the most important ones - were created also at least on paper at that time. And he just had a tremendous vision for the nation's future. He even said to a good friend of his that he'd like to go see California after the war. He said that he might even want to live out there. He wanted a couple of his sons to go out and try it out and see if maybe they'd have a better future out there. So I've taken your question and run with it, but I'm grateful for the change to morph one thing into the other. The other thing I would like to talk about in terms of the biggest surprise I got was that every morning that he was in Washington - which was almost every morning of the war - he set aside 3-4 hours to receive anybody who wanted to see him. Anybody. It had nothing to do with your status or anything else. You could be one person, a couple of people. Maybe a mother and wife pleading for clemency for a Union soldier convicted of desertion, who was going to be shot not far away from there. Every Tuesday they had executions. But every kind of thing. And nobody asked the person coming in, "What do you want to see the president about?" In a big anteroom you took your place. And in due course, you were shown in to see the president. And a couple things came out of this. I'll give you one example. A wounded soldier came in and he said, "Mr. President, I've recovered enough to be let out of the hospital. I'm trying to get back to my regiment. I haven't been able to get any pay, I haven't been able to eat, I'm hungry, can you help me?" Before he limped out of the room, Lincoln had a fleet-footed messenger on his way to the War Department, which was on the White House grounds at that time, to Secretary Stanton saying, "Secretary of War: See this man." He did that. And I think, in his leadership - and it wasn't an era of great speeches. He certainly made a couple, and we all know what they were. But I think the word got out that there was a real human being in there. Somebody who cared, somebody who could cry over what was going on, somebody agonized over this. And he also answered - he had three secretaries that were involved in the business of answering letters. And any letter that was deemed worthy at all received an answer. In fact on the first day of 1864, a man in California wrote him a letter. A totally obscure man. It just said, "I'm availing myself of the privilege as a citizen of this country to address the chief magistrate on a matter that I think is important." And those things got answered. And so the word got out there. And I think that had a lot to do with - his spine was strong, but he strengthened the Union's spine that way. He called it his "public opinion baths," these 3 or 4 hours every morning. But it was not governing by poll. It was just really getting in touch with real citizens and hearing their problems, and seeing what he could do about an individual problem when he could. But I think the effect was far greater than that. So has anybody else got something? Yes sir, please. Audience Member: 1864 is also the year when Lincoln dumped his Vice President and picked up a new one. Can you explain his relations with the first guy? And why did he see a need to replace him? Charles Flood: Excellent question, I'll be happy to do that. They're all good questions, which is just what I expected from this audience. But in any event - James Russell Lowell, the Harvard professor and, you would call him a columnist today. A pundit. He said Lincoln was elected because he had no history. And certainly Lincoln's election came as a big surprise to Salmon P. Chase and William Seward. Men who felt their resume - a term that wasn't used at the time - certainly had more impressive credentials for becoming the president. But in any case, he figured out that what he needed - he was a Republican from Illinois. He certainly needed somebody from the northeast. And here was this Democrat up in Maine who had been a Democrat, named Hannibal Hamlin. A very late comer to the Republican Party. And he thought that would be the balanced ticket. That's just - we've seen that kind of thinking since, quite a bit. But in any case, Hannibal Hamlin came in and was a typically powerless vice president. He did say of the Emancipation Proclamation that it was the great act of the age, and so on. But now we come to 1864, and Lincoln wanted to send some other signals. He wanted to send a signal to the south not that all was forgiven, but that there was a way to work together, ahead. And here was Andrew Johnson. The one senator - the senator from Tennessee, who had thrown in his lot with the Union. And he also was trying to send a signal to Europe that we're going to have a country here pretty soon - he thought, and others did as well. It wasn't certain by any means. We're going to have a reunited country, and this is a signal to Europe. We're going to have a president from the north, Illinois, and we're going to have a vice president from the South. It was symbolic, but I think it definitely entered into his calculations. Now what else needs to be said about that is, here's Lincoln in his less saintly side. And there was a fair amount of that. He sent people to the convention to represent his interests. But of his two closest associates, Nicolay and Hay, his two secretaries, one thought that Lincoln really wanted Hamlin again and one thought that he wanted Andrew Johnson. And that's how close he kept his cards to the chest. Interestingly enough - and we don't have the piece of paper, but the federal marshal of Washington, who also acted as Lincoln's bodyguard, Ward Lamon, was also sent over there. And Lamon claimed that Lincoln gave him a piece of paper and said, "Don't use it until you have to, at the last minute," saying he would prefer Andrew Johnson. But the public stance he took - or even the stance he took in talking to people - he said, "Let the convention decide." It wasn't up to the convention to decide. He had the thing absolutely wired from the beginning as to how it was to come out. So that's quite a lot on Hamlin, but it also tells you quite a lot about Lincoln and how he operated. I don't know how much time we should continue. I'm happy to go on as long as there are questions. Sir? Audience Member: I've read your book and I thought it was wonderful. You said you... Charles Flood: I'm sorry. I heard the "wonderful". I had no trouble with that. Audience Member: How did the book come into being? Charles Flood: If I may, I'll back up again. I love to begin stories where they begin. In my case, my method of selecting subjects was influenced quite a bit in 1961 when Barbara Tuchman came out with a book called "The Guns of August". And what was interesting to me about that was at that time, already, there had been - a conservative estimate - 10,000 books in English on World War I. But by isolating August of 1914, she started with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. By the end of the month - you go through the miscalculations and misperceptions and the chancelleries of Europe, and by the end of the month the guns are booming. "The Guns of August" I said to myself, "This is a really great thing." Because it's not doing it with smoke and mirrors. It's really true. It's part of a much larger story, but by isolating part of the story you have something valuable in itself. And so the first time I applied that was some years later. I did a book called "Rise and Fight Again" about the four worst American military disasters of the American Revolution. And the thesis being, "Look at all this. And yet here underneath is the spirit that finally enabled the rebels to prevail." I then used it again with "Lee: The Last Years". So much had been written on Lee, but virtually nothing had isolated the last five years of his life when he became president, as many of you know, of what was Washington College - renamed Washington Lee after his death. Then I took that in a different area. I did the early part of Adolph Hitler's political career. Again, certainly included in the full-length biographies. But quite different. How Hitler happened. Then I came down to Grant and Sherman. Which interested me, because that idea had been sitting there for that time 135 years. But nobody had picked up on it. Because it was a friendship. "Grant and Sherman: The Friendship That Won the Civil War" They were friends. Certainly one was superior to the other, but they were friends, and it was a partnership that I don't think had ever been really properly pulled out of the Civil War and shown for its immense significance. The personal relationship and the results of that. Which brings me to Lincoln. At the end of "Grant and Sherman" Lincoln is on the scene. And I kept looking at Lincoln. And I had never been much of a Lincoln man, but I kept thinking this huge, towering figure is there. And I thought, don't do that. This is like climbing Mt. Everest. I mean I didn't see the angle, if you will. But then some time after finishing "Grant and Sherman" I thought, well let's just go through his life. And 1864 hit me right between the eyes. Again, I don't think it's smoke and mirrors. It was this crucial year. All of this did come to pass during that time. So that's the long way of telling you how I arrived at that. And then the beauty of something like a year in somebody's life is there's your story. There's a great deal of chronological records of all kinds. The letters, contemporary newspaper accounts, and all that. What I also would like to say is that I say to myself, I had near me - including the splendid book "Lincoln" by David Donald, who has just died and whose obituary is in today's New York Times. But I said I'd rather start discovering my own Lincoln. So I sort of stayed away from the biographies. I had them there. I'd occasionally use them. But I didn't want somebody else's Lincoln. I wanted to get all the bits and pieces. Men who knew Lincoln and their memories of him. Not necessarily by a process of triangulation, but seeing a lot of different Lincolns from contemporaries before turning to a book that was published in 1995. So I went about it that way as well. That's how it all happened. Anybody else? Alright, well I thank you very much. You've been very attentive. I appreciate it.

References

- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Barbara Beving Long (January 15, 1990). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Gosper County Courthouse". National Park Service. and accompanying four photos from 1989

External links

![]() Media related to Gosper County Courthouse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gosper County Courthouse at Wikimedia Commons