| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (or Gibbs energy as the recommended name; symbol ) is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum amount of work, other than pressure-volume work, that may be performed by a thermodynamically closed system at constant temperature and pressure. It also provides a necessary condition for processes such as chemical reactions that may occur under these conditions. The Gibbs free energy is expressed as

- is the internal energy of the system

- is the enthalpy of the system

- is the entropy of the system

- is the temperature of the system

- is the volume of the system

- is the pressure of the system (which must be equal to that of the surroundings for mechanical equilibrium).

The Gibbs free energy change (, measured in joules in SI) is the maximum amount of non-volume expansion work that can be extracted from a closed system (one that can exchange heat and work with its surroundings, but not matter) at fixed temperature and pressure. This maximum can be attained only in a completely reversible process. When a system transforms reversibly from an initial state to a final state under these conditions, the decrease in Gibbs free energy equals the work done by the system to its surroundings, minus the work of the pressure forces.[1]

The Gibbs energy is the thermodynamic potential that is minimized when a system reaches chemical equilibrium at constant pressure and temperature when not driven by an applied electrolytic voltage. Its derivative with respect to the reaction coordinate of the system then vanishes at the equilibrium point. As such, a reduction in is necessary for a reaction to be spontaneous under these conditions.

The concept of Gibbs free energy, originally called available energy, was developed in the 1870s by the American scientist Josiah Willard Gibbs. In 1873, Gibbs described this "available energy" as[2]: 400

the greatest amount of mechanical work which can be obtained from a given quantity of a certain substance in a given initial state, without increasing its total volume or allowing heat to pass to or from external bodies, except such as at the close of the processes are left in their initial condition.

The initial state of the body, according to Gibbs, is supposed to be such that "the body can be made to pass from it to states of dissipated energy by reversible processes". In his 1876 magnum opus On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, a graphical analysis of multi-phase chemical systems, he engaged his thoughts on chemical-free energy in full.

If the reactants and products are all in their thermodynamic standard states, then the defining equation is written as , where is enthalpy, is absolute temperature, and is entropy.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:607 285329 390592 1361 960 235142 902

-

Gibbs free energy and spontaneity | Chemistry | Khan Academy

-

Gibbs Free Energy - Entropy, Enthalpy & Equilibrium Constant K

-

Using Gibbs Free Energy

-

The Laws of Thermodynamics, Entropy, and Gibbs Free Energy

-

Gibbs free energy and spontaneous reactions | Biology | Khan Academy

Transcription

We've learned over the last several videos that if we have a system undergoing constant pressure, or it's in an environment with constant pressure, that its change in enthalpy is equal to the heat added to the system. And I'll write this little p here, because that's at constant pressure. So if you have a reaction, let's say A plus B yields C and our change in enthalpy-- so our enthalpy in this state minus the change in the enthalpy in that state-- so let's say our change in enthalpy is less than 0, we know that this is exothermic. Why is that? And once again, I'm assuming constant pressure. How do we know this is exothermic, that we're releasing energy? Because change in enthalpy, when we're dealing with a constant pressure system, is heat added to the system. If the heat added to the system is negative, we must be releasing heat. So we're releasing heat or energy. So plus energy. And we learned in the last video, I think it was either the last video or a couple of videos ago, we call this an exothermic reaction. And then if you have a reaction that needs energy-- so let's say you have A plus B plus some energy yields C, then what does that mean? Well, that means that the system absorbed energy. The amount of energy you absorb is your change in enthalpy. So your delta H is going to be positive. Your change in enthalpy is positive. You've absorbed energy into the system. And we call these endothermic reactions. You're absorbing heat. Now, if we wanted to figure out whether reaction just happens by itself-- whether it's spontaneous-- it seems like this change in enthalpy is a good candidate. Obviously, if I'm releasing energy, I didn't need any energy for this reaction to happen, so maybe this reaction is spontaneous. And likewise, since I'd have to somehow add energy into the system, my gut tells me that this maybe isn't spontaneous. But there's a little part of me that says, well, you know, what if the particles are running around really fast, and they have a lot of kinetic energy that can be used to kind of ram these particles together, maybe all of a sudden this would be spontaneous. So maybe enthalpy by itself wouldn't completely describe what's going to happen. So in order to get a little intuition, and to maybe build up our sense of whether a reaction happens spontaneously, let's think about the ingredients that probably matter. We already know that delta H probably matters. If we release energy-- you know, delta H less than 0, that tends to make me think it might be spontaneous. But what if our delta S, what if our entropy goes down? What if things become more ordered? We've already learned from the second law of thermodynamics, that that doesn't tend to be the case. And just from personal experience, we know that things on their own just don't kind of go to the macro state that has fewer micro states, you know. An egg doesn't just put itself together, and bounce, and kind of jump off the floor on its own, although there's some probability it would happen. So it seems like entropy matters somewhat. And then there's the idea of temperature. Because I already talked about, when I talked about energy here. I was like, well, you know, even if this requires energy, maybe if the temperature is high enough, maybe I could actually ram these particles together in some way, and kind of create energy to go here. So let's think about-- so let's see. let's think about the ingredients, and let's think about what the reactions would look like depending on different combinations of the ingredients. So the ingredients I'm going to deal with-- delta H seems to definitely matter, whether or not we absorb energy or not. We have delta S, our change in entropy. Does the system take on more states or fewer states? Does it become more or less ordered? And then there's temperature, which is average kinetic energy. So let's just think about a whole bunch of situations. So let's think of the first case. Let's think of the situation where our delta H is less than 0, and our entropy is greater than 0. I mean, my gut already tells me that this is going to happen. This is a situation where we're going to be more entropic after the reaction. So one way of looking at entropy, you could more states. Maybe we have more particles. We've seen that entropy is related to the number of particles we have. So this could be a reaction where let's say we have this-- see, we want to have more particles. So let's say I have that guy. And say he's got one guy like that there, and then I have another guy like this, and let's say he's got a molecule like this. Let's say that a more-- well, I won't say stable or not. But let's say that when these guys bump into each other, you end up with this. And I'm making things up on the fly. Maybe one of these molecules bonds with this molecule, so you have one of the dark blues. I'll draw all the dark blues. Bonds with this light blue molecule, one of the dark blues bonds with the magenta molecule. And maybe that brown molecule just gets knocked off all by himself. So we went from having two molecules to having three molecules. We have more disorder, more entropy. This can obviously take on more states. And I'm telling you that delta H is less than 0. So by doing this, these guys, their electrons are in a lower potential, or they're in a more stable configuration. So when the electrons go from their higher potential configurations over here, and they become more stable, they release energy. So you have plus-- and then I just know that, because I said from the beginning that my change in enthalpy is less than 0. So plus some energy. So it seems pretty obvious to me that this reaction is going to be spontaneous in this rightward direction. Because there's no reason why-- first of all, it's much easier for two particles to bump into each other just right to go in that direction than it is for three particles-- if you just think of it from a probability point of view-- for three particles to get together just right and go in that direction. And even more, these guys are more stable. Their electrons are in a lower potential state. So there's no even kind of enthalpic reason for them to move in this direction, or you know, kind of a energy reason for them to move in this direction. So this, to me, I kind of have the intuition that regardless of what the temperature is, we're going to favor this forward reaction. So I would say that this is probably spontaneous. Now, what happens-- let's do something that's maybe a little less intuitive. What happens if my delta H is less than 0? But let's say I lose entropy. And this seems, you know, with second law of thermodynamics, if the entropy of the universe goes up. I'm just talking about my system. But let's say I lose entropy. So that would be a situation where I go from, let's say, two particles. Let's say I got that particle, and then I have this particle. And then, if they bump into each other just right, their electrons are going to be more stable, and maybe they form this character. And when they do that, the electrons can enter into lower potential states, and when they do, the electrons release energy, so you have some plus energy here. And we know that, because this was the change in enthalpy was less than zero. We have lower energy in this state than that one, and the difference is released right here. Now will this reaction happen? Well, it seems like-- let's introduce our temperature. What's going to happen at low temperatures? At low temperatures, these guys have a very low average kinetic energy. They're just drifting around very slowly. And as they drift around very slowly-- And remember, when I talk about spontaneity-- I wrote sponteous. This is spontaneous. Sponteous should be another thermodynamic. It's a fun word. When I talk about spontaneity, I'm just talking about whether the reaction is just going to happen on its own. I'm not talking about how fast, or the rate of the reaction. That's a key thing to know. You know, is this going to happen. I don't care if it takes, you know, a million years for the thing to happen. I just want to know, is it going to happen on its own? So if the temperature is slow, these guys might be really creeping along, barely bumping into each other. But they will eventually bump into each other. And when they do, they're just drifting past each other. And when they drift past each other, they will configure themselves in a way-- things want to go to a lower potential state. I'm just trying to give you kind of a hand-wavey, rough intuition of things. But because this will release energy, and it will go to a lower potential state, the electrons kind of configure themselves when they get near each other, and enter into this state. And they release energy. And once the energy is gone, and maybe it's in the form of heat or whatever it is, it's hard to kind of get it back and go on in other direction. So it seems like this would be spontaneous if the temperature is low. So let me write that. Spontaneous if the temperate is low. Now what happens if the temperature is high? Remember, these aren't the only particles here. We have more. You know, I'll have another guy like that, and another guy like that. And then this, on this side, I'll have, you know, more particles. There's obviously not just one particle. Then all of these macro variables really make no sense, if we're just talking about particular molecules. We're talking about entire systems. But what happens here if the temperature of our system is high? So let's think of a situation where the temperature is high. Now all of a sudden-- so on the side, people are going to be knocking into each other super fast. You know, if this guy bumps into this guy super fast, you can almost view it as a car collision. Well, even better, this could be car collision. If these were each individual cars, and the atoms were the components of the cars, if they're like smashing into each other, even though they want to be attached to each other, they have screws and whatever else that are holding it together-- if two cars run into each other fast enough, all that screws and the glue and the welding won't matter. They're just going to blow apart. So high kinetic energy-- let me draw that. So if they have high kinetic energy, my gut tells me that on the side of the reaction, these guys are just going to blow each other apart to this side. And these guys, since these guys also have high kinetic energy, they're going to be moving so fast past each other, and they're going to ricochet off of each other so fast, that the counteracting force, or the contracting inclination for their electrons to get more stably configured, won't matter. It's like, imagine trying to attach a tire to something while you're running past the car. You kind of have to do it-- even though that's a more-- well, maybe the analogy is getting weak, here. But I think you get the idea that if the temperature's really high, it seems less likely that these guys are going to kind of drift near each other just right to be able to attach to each other, and their electrons to get more stable, and to do this whole exothermic thing. So my sense is that if the temperature is high enough-- I mean, you know, maybe say, oh, that's not high enough. But what if it's super high temperatures? If it's super high temperatures, then maybe even this guy will bump into that. Instead of forming that, he'll knock this other blue guy off, and then he'll be over here. I should do the blue guy in blue. And maybe he'll knock this guy into his constituent particles, if there's enough kinetic energy. So here I get the idea that it's not spontaneous. And even more, the reverse reaction, if the temperature is high enough, is probably going to be spontaneous. If the temperature is high enough, these guys are going to react, are going to bump into each other, and the reaction is going to go that way. So temperature is high, you go that way, temperature is low, you go that way. So let's see if we can put everything together that we've seen so far and kind of come up with a gut feeling of what a formula for spontaneity would look like. So we could start with enthalpy. So we already know that look, if this is less than 0, we're probably dealing with something that's spontaneous. Now let's say I want a whole expression, where if the whole expression is less than 0, it tells me that it's going to be spontaneous. So we know that positive entropy is something good for spontaneity. We saw that in every situation here. That if we have more states, it's always a good thing. It's more likely to make something spontaneous. Now, we want our whole expression to be negative if it's spontaneous, right? So positive entropy should make my whole expression more negative, so maybe we should subtract entropy. Right? If this is positive, then my whole expression will be more negative. Which tells me, hey, this is spontaneous. So if this is negative, we're releasing energy. And then if this is positive, we're getting more disordered, so this whole thing will be negative. So that seems good. Now what if entropy is negative? If entropy is negative, this also kind of speaks to the idea that if entropy is negative, it kind of makes the reaction a little less spontaneous. Right? In this situation, entropy was negative. We went from more disorder to less disorder, or fewer particles. And what did we say? When temperature is high, entropy matters a lot. When temperature is high, this less entropic state, they ram into each other, and they'll become more entropic. When temperature is low, maybe they'll drift close to each other, and then the enthalpy part of the equation will matter more. So let's see if we can weight that. So when temperature is high, entropy matters. When temperature is low, entropy doesn't matter. So what if we just scaled entropy by temperature? What if I just took a temperature variable here? Now, my claim, or my intuition, based on everything we've experimented so far, is that if this expression is less than 0, we should be dealing with a spontaneous reaction. And let's see if it gels with everything we say here. If the temperature is high-- so this reaction right here was exothermic, in the rightwards direction. When we go to the right, from more of these molecules to these fewer ones, I told you it's exothermic. Now, at low temperatures, my gut told me, hey, this should be spontaneous. These guys are going to drift close to each other, and get into this more stable configuration. And that makes sense. At low temperatures, this term isn't going to matter much. You can imagine the extreme. At absolute 0, this term is going to disappear. You can't quite reach there, but it would become less and less. And this term dominates. Now, at high temperatures, all of a sudden, this term is going to dominate. And if our delta S is less than 0, then this whole term is going to dominate and become positive. Right? And even if this is negative, we're subtracting. So our delta S is negative. We put a negative here. So this is going to be a positive. So this positive, if the temperature is high enough-- and remember, we're dealing with Kelvin, so temperature can only be positive. If this is positive enough, it will overwhelm any negative enthalpy. And so it won't be spontaneous anymore. And so if the temperature is high enough, this direction won't be spontaneous. And this equation tells us this. And then if we go to the negative enthalpy, positive entropy, so we're releasing energy, so this is negative, and our entropy is increasing-- our entropy, we're getting more disordered-- then this becomes a negative as well. So our thing is definitely going to be negative. And we already had the sense that look, if this is negative and this is positive, we're getting more entropic and we're releasing energy, that should definitely be spontaneous. And this equation also speaks to that. So so far, I feel pretty good about this equation. And as you can imagine, I didn't think of this out of the blue. This actually is the equation that predicts spontaneity. And I'm going to show it to you in a slightly more rigorous way in the future, maybe going back to some of our fundamental formulas for entropy and things like that. But this is the formula for whether something is spontaneous. And what I wanted to do in this video is just give you an intuition why this formula kind of makes sense. And this quantity right here is called the delta G, or change in Gibbs free energy. And this is what does predict whether a reaction is spontaneous. So in the next video, I'll actually apply this formula a couple of times. And then a few videos after that, we'll do a little bit more of how you can actually get this from some of our basic thermodynamic principles.

Overview

According to the second law of thermodynamics, for systems reacting at fixed temperature and pressure without input of non-Pressure Volume (pV) work, there is a general natural tendency to achieve a minimum of the Gibbs free energy.

A quantitative measure of the favorability of a given reaction under these conditions is the change ΔG (sometimes written "delta G" or "dG") in Gibbs free energy that is (or would be) caused by the reaction. As a necessary condition for the reaction to occur at constant temperature and pressure, ΔG must be smaller than the non-pressure-volume (non-pV, e.g. electrical) work, which is often equal to zero (then ΔG must be negative). ΔG equals the maximum amount of non-pV work that can be performed as a result of the chemical reaction for the case of a reversible process. If analysis indicates a positive ΔG for a reaction, then energy — in the form of electrical or other non-pV work — would have to be added to the reacting system for ΔG to be smaller than the non-pV work and make it possible for the reaction to occur.[3]: 298–299

One can think of ∆G as the amount of "free" or "useful" energy available to do non-pV work at constant temperature and pressure. The equation can be also seen from the perspective of the system taken together with its surroundings (the rest of the universe). First, one assumes that the given reaction at constant temperature and pressure is the only one that is occurring. Then the entropy released or absorbed by the system equals the entropy that the environment must absorb or release, respectively. The reaction will only be allowed if the total entropy change of the universe is zero or positive. This is reflected in a negative ΔG, and the reaction is called an exergonic process.

If two chemical reactions are coupled, then an otherwise endergonic reaction (one with positive ΔG) can be made to happen. The input of heat into an inherently endergonic reaction, such as the elimination of cyclohexanol to cyclohexene, can be seen as coupling an unfavorable reaction (elimination) to a favorable one (burning of coal or other provision of heat) such that the total entropy change of the universe is greater than or equal to zero, making the total Gibbs free energy change of the coupled reactions negative.

In traditional use, the term "free" was included in "Gibbs free energy" to mean "available in the form of useful work".[1] The characterization becomes more precise if we add the qualification that it is the energy available for non-pressure-volume work.[4] (An analogous, but slightly different, meaning of "free" applies in conjunction with the Helmholtz free energy, for systems at constant temperature). However, an increasing number of books and journal articles do not include the attachment "free", referring to G as simply "Gibbs energy". This is the result of a 1988 IUPAC meeting to set unified terminologies for the international scientific community, in which the removal of the adjective "free" was recommended.[5][6][7] This standard, however, has not yet been universally adopted.

The name "free enthalpy" was also used for G in the past.[6]

History

The quantity called "free energy" is a more advanced and accurate replacement for the outdated term affinity, which was used by chemists in the earlier years of physical chemistry to describe the force that caused chemical reactions.

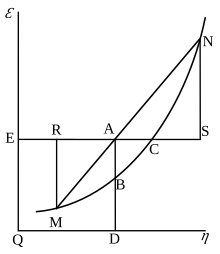

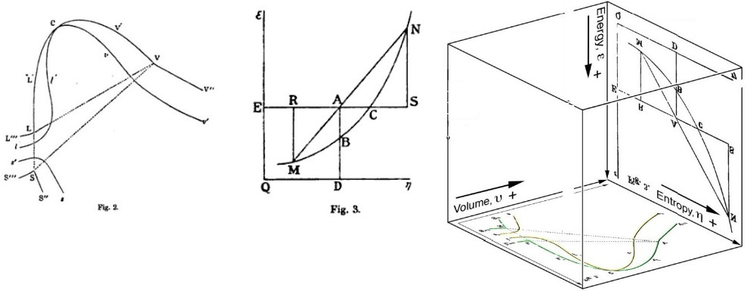

In 1873, Josiah Willard Gibbs published A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces, in which he sketched the principles of his new equation that was able to predict or estimate the tendencies of various natural processes to ensue when bodies or systems are brought into contact. By studying the interactions of homogeneous substances in contact, i.e., bodies composed of part solid, part liquid, and part vapor, and by using a three-dimensional volume-entropy-internal energy graph, Gibbs was able to determine three states of equilibrium, i.e., "necessarily stable", "neutral", and "unstable", and whether or not changes would ensue. Further, Gibbs stated:[2]

If we wish to express in a single equation the necessary and sufficient condition of thermodynamic equilibrium for a substance when surrounded by a medium of constant pressure p and temperature T, this equation may be written:

δ(ε − Tη + pν) = 0when δ refers to the variation produced by any variations in the state of the parts of the body, and (when different parts of the body are in different states) in the proportion in which the body is divided between the different states. The condition of stable equilibrium is that the value of the expression in the parenthesis shall be a minimum.

In this description, as used by Gibbs, ε refers to the internal energy of the body, η refers to the entropy of the body, and ν is the volume of the body...

Thereafter, in 1882, the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz characterized the affinity as the largest quantity of work which can be gained when the reaction is carried out in a reversible manner, e.g., electrical work in a reversible cell. The maximum work is thus regarded as the diminution of the free, or available, energy of the system (Gibbs free energy G at T = constant, P = constant or Helmholtz free energy F at T = constant, V = constant), whilst the heat given out is usually a measure of the diminution of the total energy of the system (internal energy). Thus, G or F is the amount of energy "free" for work under the given conditions.

Until this point, the general view had been such that: "all chemical reactions drive the system to a state of equilibrium in which the affinities of the reactions vanish". Over the next 60 years, the term affinity came to be replaced with the term free energy. According to chemistry historian Henry Leicester, the influential 1923 textbook Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances by Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall led to the replacement of the term "affinity" by the term "free energy" in much of the English-speaking world.[8]: 206

Definitions

The Gibbs free energy is defined as

which is the same as

where:

- U is the internal energy (SI unit: joule),

- p is pressure (SI unit: pascal),

- V is volume (SI unit: m3),

- T is the temperature (SI unit: kelvin),

- S is the entropy (SI unit: joule per kelvin),

- H is the enthalpy (SI unit: joule).

The expression for the infinitesimal reversible change in the Gibbs free energy as a function of its "natural variables" p and T, for an open system, subjected to the operation of external forces (for instance, electrical or magnetic) Xi, which cause the external parameters of the system ai to change by an amount dai, can be derived as follows from the first law for reversible processes:

where:

- μi is the chemical potential of the i-th chemical component. (SI unit: joules per particle[9] or joules per mole[1])

- Ni is the number of particles (or number of moles) composing the i-th chemical component.

This is one form of the Gibbs fundamental equation.[10] In the infinitesimal expression, the term involving the chemical potential accounts for changes in Gibbs free energy resulting from an influx or outflux of particles. In other words, it holds for an open system or for a closed, chemically reacting system where the Ni are changing. For a closed, non-reacting system, this term may be dropped.

Any number of extra terms may be added, depending on the particular system being considered. Aside from mechanical work, a system may, in addition, perform numerous other types of work. For example, in the infinitesimal expression, the contractile work energy associated with a thermodynamic system that is a contractile fiber that shortens by an amount −dl under a force f would result in a term f dl being added. If a quantity of charge −de is acquired by a system at an electrical potential Ψ, the electrical work associated with this is −Ψ de, which would be included in the infinitesimal expression. Other work terms are added on per system requirements.[11]

Each quantity in the equations above can be divided by the amount of substance, measured in moles, to form molar Gibbs free energy. The Gibbs free energy is one of the most important thermodynamic functions for the characterization of a system. It is a factor in determining outcomes such as the voltage of an electrochemical cell, and the equilibrium constant for a reversible reaction. In isothermal, isobaric systems, Gibbs free energy can be thought of as a "dynamic" quantity, in that it is a representative measure of the competing effects of the enthalpic[clarification needed] and entropic driving forces involved in a thermodynamic process.

The temperature dependence of the Gibbs energy for an ideal gas is given by the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation, and its pressure dependence is given by[12]

or more conveniently as its chemical potential:

In non-ideal systems, fugacity comes into play.

Derivation

The Gibbs free energy total differential with respect to natural variables may be derived by Legendre transforms of the internal energy.

The definition of G from above is

- .

Taking the total differential, we have

Replacing dU with the result from the first law gives[13]

The natural variables of G are then p, T, and {Ni}.

Homogeneous systems

Because S, V, and Ni are extensive variables, an Euler relation allows easy integration of dU:[13]

Because some of the natural variables of G are intensive, dG may not be integrated using Euler relations as is the case with internal energy. However, simply substituting the above integrated result for U into the definition of G gives a standard expression for G:[13]

This result shows that the chemical potential of a substance is its (partial) mol(ecul)ar Gibbs free energy. It applies to homogeneous, macroscopic systems, but not to all thermodynamic systems.[14]

Gibbs free energy of reactions

The system under consideration is held at constant temperature and pressure, and is closed (no matter can come in or out). The Gibbs energy of any system is and an infinitesimal change in G, at constant temperature and pressure, yields

- .

By the first law of thermodynamics, a change in the internal energy U is given by

where δQ is energy added as heat, and δW is energy added as work. The work done on the system may be written as δW = −pdV + δWx, where −pdV is the mechanical work of compression/expansion done on or by the system and δWx is all other forms of work, which may include electrical, magnetic, etc. Then

and the infinitesimal change in G is

- .

The second law of thermodynamics states that for a closed system at constant temperature (in a heat bath), , and so it follows that

Assuming that only mechanical work is done, this simplifies to

This means that for such a system when not in equilibrium, the Gibbs energy will always be decreasing, and in equilibrium, the infinitesimal change dG will be zero. In particular, this will be true if the system is experiencing any number of internal chemical reactions on its path to equilibrium.

In electrochemical thermodynamics

When electric charge dQele is passed between the electrodes of an electrochemical cell generating an emf , an electrical work term appears in the expression for the change in Gibbs energy:

The combination (, Qele) is an example of a conjugate pair of variables. At constant pressure the above equation produces a Maxwell relation that links the change in open cell voltage with temperature T (a measurable quantity) to the change in entropy S when charge is passed isothermally and isobarically. The latter is closely related to the reaction entropy of the electrochemical reaction that lends the battery its power. This Maxwell relation is:[15]

If a mole of ions goes into solution (for example, in a Daniell cell, as discussed below) the charge through the external circuit is

where n0 is the number of electrons/ion, and F0 is the Faraday constant and the minus sign indicates discharge of the cell. Assuming constant pressure and volume, the thermodynamic properties of the cell are related strictly to the behavior of its emf by

where ΔH is the enthalpy of reaction. The quantities on the right are all directly measurable.

Useful identities to derive the Nernst equation

During a reversible electrochemical reaction at constant temperature and pressure, the following equations involving the Gibbs free energy hold:

- (see chemical equilibrium),

- (for a system at chemical equilibrium),

- (for a reversible electrochemical process at constant temperature and pressure),

- (definition of ),

and rearranging gives

which relates the cell potential resulting from the reaction to the equilibrium constant and reaction quotient for that reaction (Nernst equation),

where

- ΔrG, Gibbs free energy change per mole of reaction,

- ΔrG°, Gibbs free energy change per mole of reaction for unmixed reactants and products at standard conditions (i.e. 298 K, 100 kPa, 1 M of each reactant and product),

- R, gas constant,

- T, absolute temperature,

- ln, natural logarithm,

- Qr, reaction quotient (unitless),

- Keq, equilibrium constant (unitless),

- welec,rev, electrical work in a reversible process (chemistry sign convention),

- n, number of moles of electrons transferred in the reaction,

- F = NAe ≈ 96485 C/mol, Faraday constant (charge per mole of electrons),

- , cell potential,

- , standard cell potential.

Moreover, we also have

which relates the equilibrium constant with Gibbs free energy. This implies that at equilibrium

Standard Gibbs energy change of formation

| Substance (state) |

ΔfG° | |

|---|---|---|

| (kJ/mol) | (kcal/mol) | |

| NO(g) | 87.6 | 20.9 |

| NO2(g) | 51.3 | 12.3 |

| N2O(g) | 103.7 | 24.78 |

| H2O(g) | −228.6 | −54.64 |

| H2O(l) | −237.1 | −56.67 |

| CO2(g) | −394.4 | −94.26 |

| CO(g) | −137.2 | −32.79 |

| CH4(g) | −50.5 | −12.1 |

| C2H6(g) | −32.0 | −7.65 |

| C3H8(g) | −23.4 | −5.59 |

| C6H6(g) | 129.7 | 29.76 |

| C6H6(l) | 124.5 | 31.00 |

The standard Gibbs free energy of formation of a compound is the change of Gibbs free energy that accompanies the formation of 1 mole of that substance from its component elements, in their standard states (the most stable form of the element at 25 °C and 100 kPa). Its symbol is ΔfG˚.

All elements in their standard states (diatomic oxygen gas, graphite, etc.) have standard Gibbs free energy change of formation equal to zero, as there is no change involved.

- ΔfG = ΔfG˚ + RT ln Qf,

where Qf is the reaction quotient.

At equilibrium, ΔfG = 0, and Qf = K, so the equation becomes

- ΔfG˚ = −RT ln K,

where K is the equilibrium constant of the formation reaction of the substance from the elements in their standard states.

Graphical interpretation by Gibbs

Gibbs free energy was originally defined graphically. In 1873, American scientist Willard Gibbs published his first thermodynamics paper, "Graphical Methods in the Thermodynamics of Fluids", in which Gibbs used the two coordinates of the entropy and volume to represent the state of the body. In his second follow-up paper, "A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces", published later that year, Gibbs added in the third coordinate of the energy of the body, defined on three figures. In 1874, Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell used Gibbs' figures to make a 3D energy-entropy-volume thermodynamic surface of a fictitious water-like substance.[17] Thus, in order to understand the concept of Gibbs free energy, it may help to understand its interpretation by Gibbs as section AB on his figure 3, and as Maxwell sculpted that section on his 3D surface figure.

See also

- Bioenergetics

- Calphad (CALculation of PHAse Diagrams)

- Critical point (thermodynamics)

- Electron equivalent

- Enthalpy-entropy compensation

- Free entropy

- Gibbs–Helmholtz equation

- Grand potential

- Non-random two-liquid model (NRTL model) – Gibbs energy of excess and mixing calculation and activity coefficients

- Spinodal – Spinodal Curves (Hessian matrix)

- Standard molar entropy

- Thermodynamic free energy

- UNIQUAC model – Gibbs energy of excess and mixing calculation and activity coefficients

Notes and references

- ^ a b c Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- ^ a b Gibbs, Josiah Willard (December 1873). "A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces" (PDF). Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2: 382–404.

- ^ Peter Atkins; Loretta Jones (1 August 2007). Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-0965-6.

- ^ Reiss, Howard (1965). Methods of Thermodynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-69445-3.

- ^ Calvert, J. G. (1 January 1990). "Glossary of atmospheric chemistry terms (Recommendations 1990)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 62 (11): 2167–2219. doi:10.1351/pac199062112167.

- ^ a b "Gibbs energy (function), G". IUPAC Gold Book (Compendium of Chemical Technology). IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry). 2008. doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02629. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

It was formerly called free energy or free enthalpy.

- ^ Lehmann, H. P.; Fuentes-Arderiu, X.; Bertello, L. F. (1 January 1996). "Glossary of terms in quantities and units in Clinical Chemistry (IUPAC-IFCC Recommendations 1996)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 68 (4): 957–1000. doi:10.1351/pac199668040957. S2CID 95196393.

- ^ Henry Marshall Leicester (1971). The Historical Background of Chemistry. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-61053-5.

- ^ Chemical Potential, IUPAC Gold Book.

- ^ Müller, Ingo (2007). A History of Thermodynamics – the Doctrine of Energy and Entropy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46226-2.

- ^ Katchalsky, A.; Curran, Peter F. (1965). Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics in Biophysics. Harvard University Press. CCN 65-22045.

- ^ Atkins, Peter; de Paula, Julio (2006). Atkins' Physical Chemistry (8th ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 109. ISBN 0-7167-8759-8.

- ^ a b c Salzman, William R. (2001-08-21). "Open Systems". Chemical Thermodynamics. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Brachman, M. K. (1954). "Fermi Level, Chemical Potential, and Gibbs Free Energy". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 22 (6): 1152. Bibcode:1954JChPh..22.1152B. doi:10.1063/1.1740312.

- ^ H. S. Harned, B. B. Owen, The Physical Chemistry of Electrolytic Solutions, third edition, Reinhold Publishing Corporation, N.Y.,1958, p. 2-6

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 2009, pp. 5-4–5-42, 90th ed., Lide.

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell, Elizabeth Garber, Stephen G. Brush, and C. W. Francis Everitt (1995), Maxwell on heat and statistical mechanics: on "avoiding all personal enquiries" of molecules, Lehigh University Press, ISBN 0-934223-34-3, p. 248.

External links

- IUPAC definition (Gibbs energy)

- Gibbs Free Energy – Georgia State University