C. K. G. Billings | |

|---|---|

C.K.G. Billings with his horse Lou Dillon after winning the Webster Cup in 1903 | |

| Born | September 17, 1861 |

| Died | May 6, 1937 (aged 75) |

| Resting place | Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois |

Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings (September 17, 1861 – May 6, 1937) was an American industrialist tycoon,[1] philanthropist, art collector, and a noted horseman and horse breeder.[2][3] Billings invested much of his time and money promoting the sport of trotting, also known as "harness racing" or "matinee racing".[3]

Life and career

Billings was born in Saratoga, New York, on September 17, 1861, the son of Albert M. Billings, a resident of Vermont,[3] and Augusta S. Billings née Farnsworth. He was raised in Chicago, Illinois, from the age of three, attended schools in Chicago, and then Racine College in Racine, Wisconsin. When he finished college at 17 in 1879, he joined the Peoples Gas Light and Coke Company – of which his father was a principal investor and president – beginning as a laborer.[2][3][4] After becoming the firm's president in 1887,[2] he brought about the mergers from 1895 to 1910 of 12 gas companies into Peoples Gas.[5] He became chairman of the board of the company in 1901, a position he held until 1911.[2]

In 1885, Billings married Blanche E. MacLeish, whose father, Andrew MacLeish, was one of the founders of the Chicago department store Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company.[2][3] They had a son, Albert Merritt Billings, who died in 1926;[2] Billings endowed the Billings Memorial Hospital in Chicago in his memory.[3] They also had a daughter, who married Halstead Van der Poel.[3]

During his years in Chicago, Billings was the founder and a charter member of the Chicago Athletic Club and served on the West Park Commission and on the board of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.[3]

In 1901, at the age of 40, Billings, who had inherited a controlling interest in Peoples Gas but had retired from the day-to-day running of the company,[4] moved to Manhattan, New York City, where he and his family lived in a townhouse on Fifth Avenue at 53rd Street.[6]

Horses

Billings owned 75 racing or trotting horses. He later owned an extensive estate in Upper Manhattan, on the site of what is now Fort Tryon Park, and first built a 25,000-square-foot (2,300 m2) stable there, at the cost of $200,000. The stable, which was 250 feet (76 m) long and 125 feet (38 m) wide and two stories tall "with numerous towers and cupolas", had 22 box stalls and 9 straight stalls, a 75-foot (23 m) outdoor training ring, a 40-foot (12 m)-by-50-foot (15 m) sleigh room, feed rooms, a hayloft, and a 5,000-bushel zinc-lined granary. It also had a gymnasium, a blacksmith shop with forge, a trophy room to display Billings' awards from the amateur races he won, and two five-room suites of living quarters. The interior was designed in oak and Georgia pine. The stable had steam heat, electric light, and hot water, all provided by its dynamo room. About twenty-five men were employed there.[7]

Near the stable was a 14-room 50-foot (15 m)-by-100-foot (30 m) lodge for guests, which featured an 80-foot (24 m)-tall observation tower.[7]

The site was conveniently near the Harlem Speedway, built in 1894-89[8][9][10] for the exclusive use of riders on horseback and horse-drawn carriages. It ran from West 155th Street to Dyckman Street. and was used by rich New Yorkers to train their horses and size up those of their friends and competitors.[8][11] The Speedway was eventually paved and became the beginning of the Harlem River Drive.[11][12]

In 1903, when the stable was completed, Billings was a prominent member of the Jockey Club and part-owner of the Jamaica Race Course in Jamaica, Queens;[2] he was regarded as a "Grand Marshal" of harness racing ("trotting" or "matinee racing").[13]

Dinner on horseback

Billings wished to celebrate the completion of his trotting stable, and his selection to be the head of the New York Equestrian Club, by giving a dinner for 36 of his male horse-riding friends in the stable on March 29, 1903. He engaged the noted restaurateur Louis Sherry to cater the event, but then to avoid reporters who staked out the estate after news of the dinner had spread, changed the venue at Sherry's suggestion to the grand ballroom of Sherry's restaurant at Fifth Avenue and 44th Street. The ballroom was decorated to look like an English country estate, complete with imitation brooks. The floor was covered with turf. Billings and his guests ate mounted in a circle on 32 docile horses that were rented from nearby riding academies and brought to the fourth-floor ballroom via the freight elevator; specially built silver trays were attached to their saddles and diners drank through rubber tubes connected to iced bottles of champagne in their saddlebags. The waiters, one for each diner, served the numerous courses dressed as grooms at a fox hunt, while an elaborately dressed groom attended each horse, and near the end of the evening elaborate troughs filled with oats were brought in for the horses to eat from.[1][14][15][16] The evening concluded with a vaudeville show.[16]

The $50,000 bill for the dinner (equivalent to $1,700,000 in 2023) included the cost of a photographer from the Byron Company to document the event.[14][15]

Two days later, Billings officially opened his new stable with a luncheon for members of the Equestrian Club and other wealthy horsemen and dignitaries from around the country. Some rode there on horseback, but most traveled by elevated train to the 155th Street station located at the Harlem Speedway, and were conveyed to the stable by automobiles.[16]

In November 1905, just two years after his stable was completed, Billings sold his stock of horses at Madison Square Garden, saying that he proposed to go abroad for a few years. He held back only three horses from the sale, plus one that was withdrawn because it was lame. The sale of 18 horses brought in $46,270, with the top seller bringing in $10,500.[17]

Estates

Tryon Hall

The Billings' mansion at West 196th Street and Fort Washington Road[16] was a Louis XIV-style chateau designed by Guy Lowell, who enlarged the lodge that had been built as part of the stables. It was organized around a central courtyard with a fountain. Landscape architect Charles Downing Lay designed the grounds. Billings called it "Tryon Hall" after Fort Tryon, which had been located there and was named for Sir William Tryon, the last Governor of the English colony of New York.[6][18] The mansion stood on one of the highest points in Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River to the west and the Broadway Valley to the east, and had an observatory tower topped by an octagonal room with a 360-degree unobstructed view. The mansion stood 250 feet (76 m) above the Hudson and encompassed 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2).[19]

By 1907, Billings, his wife, two children, and 23 servants had moved there from their Manhattan townhouse. The estate included a casino with a swimming pool, squash court and bowling alley for entertaining, as well as Billings' extensive stables and an area to exercise his horses.[6][20] In the nearby Hudson, Billings kept his 232-foot (71 m) yacht, Vanadis, which was built in 1908.[21]

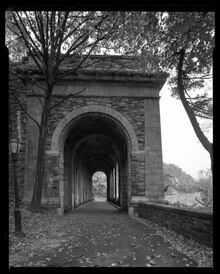

The entrance to the 25-acre (10 ha) estate[19] was originally at the top of the hill, approached via Riverside Drive and West 181st Street to Fort Washington Road, but the upper part of Riverside Drive was completed at about the same time as Billings' mansion, and he wanted a driveway connecting the mansion directly to that section of the roadway. Unfortunately, there was a steep 100-foot (30 m) cliff between the road and the mansion. Billings hired the firm of Buchman & Fox to find a solution, which they did: granite was removed from the cliff to allow a passage for a zig-zagging driveway, and the stone was then used both as a retaining wall and for the construction of an arched viaduct that supported the driveway. The arched passage became known as the "Billings Arcade". At the entrance to the driveway were gates 20 feet (6.1 m) tall and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, supported by 16-foot (4.9 m) granite pillars, which are still extant and were renovated in 2020.[6]

The entire driveway project took more than a hundred workers a year to complete, at the cost of $250,000, and raised the overall cost of the estate to more than $2 million.[6] The Billings Arcade remains as part of Fort Tryon Park, as does part of the driveway, now used as a pedestrian path. Another remnant is a gardener's cottage, originally a gatehouse for the estate's upper entrance, now used for park offices. The gateposts of the driveway entrance were refurbished in 2017. The driveway no longer connects to the roadway that was once Riverside Drive and is now the northbound side of the Henry Hudson Parkway.

Billings sold his Tryon Hall estate in 1917 to John D. Rockefeller Jr.[22] The Billings family had already moved into a 21-room apartment on Fifth Avenue and 63rd Street, for which he paid $20,000 a year in rent. Rockefeller was assembling parcels, including the neighboring Hays and Shaefer estates[19] for the creation of a park designed by the Olmsted Brothers, which he planned to develop and then give to the city – this eventually became Fort Tryon Park. He intended to tear down Tryon Hall but was held back by popular sentiment. During World War I, he offered use of the house to the U.S. government as a hospital, and was prepared to outlay $500,000 for the conversion, but this did not happen. There was also some discussion about it being used as the mayor's official residence, or using it as the site of a museum.[19] The mansion was later rented to drug manufacturer Nicolas C. Partos of the Partola Manufacturing Company, at first for the summer of 1918, but then for several years. Partos and his family were still in residence when the building burned down on March 7, 1926.[6][18][23][24]

Farnsworth

After leaving Tryon Hall, Billings moved to another grand estate he had built, this one called "Farnsworth" for his mother's family[2] and located in Locust Valley, New York, on Long Island. It was again designed by Guy Lowell, this time in the Georgian Revival style, with the extensive grounds landscaped by Andrew Robeson Sargent of Boston. Despite the Georgian style of the house, it was designed around a central patio in the manner of an Italian villa. The house had 11 master bedrooms with 9 baths and 19 servants' bedrooms with 4 baths. The appointments were expensive and luxurious; the estate buildings alone cost $1,550,000 in 1915.[25]

Despite its grandeur, Billings did not stay in Farnsworth any longer than he had in Tryon Hall. With World War 1 raging and his health failing, he began to sell off his East Coast properties in preparation for moving to California.[3][25]

As he had at Tryon Hall, Billings moored his yacht Vanadis in the nearby waters. In 1916, he had sold the original Vanadis to Morton F. Plant in return for the smaller yacht Kanawha, after the Vanadis struck the steamship Bunker Hill, killing two people.[2][21] In 1924, Billings ordered a second, larger yacht – 246 feet (75 m) long – which he also named Vanadis.[26] This ship was later rechristened Lady Hutton after the actress Barbara Hutton, a later owner, and is anchored at Riddarholmen in Stockholm, where it serves as the Mälardrottningen hotel.[27][28][29]

Other estates

At various times, Billings also owned a 5,000-acre (2,000 ha) estate on the James River in Virginia called Curles Neck Farm, which he bought in 1913 and developed into one of the country's prime horse-breeding facilities, an estate in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and a summer home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.[2][6]

When he moved to Santa Barbara, California, in 1917, Billings had a mansion built in the hills, which he called "Asombrosa". It was damaged by an earthquake in the mid-1930s, and he had another, smaller house built nearby.[3]

Later life

In 1911, Billings became the Chairman of the Board of Union Carbide and Carbon Company – a company he helped to found[3] – he held that position until his death in 1937. His mother died in 1913, leaving him $450,000; at that time his net worth was estimated to be $30 million,[2] equivalent to $925 million in 2023. At one time he was reported to be one of the five richest men in the United States.[3]

Around 1915, Billings – a member of the Turf and Field Club at Belmont Park[3] – was said to be the owner of the fastest stallio, mare, and gelding in the world. He was also part-owner of the Kentucky Derby-winning Omar Khayyam.[2] He was the principal investor in the Billings Parks race track in Memphis, Tennessee, which eventually closed because of anti-betting laws passed by that state. At one time he bought a controlling interest in the Kentucky Breeder's Association, preventing it from going under. The association was reorganized, and Billings later donated his stock to the group.[3]

After moving to California in 1917, Billings maintained ownership of "Farnsworth" on Long Island, where he kept some of his horses.[2] Others were kept at the Glenville Race Track in Cleveland, Ohio.[3]

In 1926, Billings sold his art collection, which included works by Jean-Charles Cazin, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, John Crome, Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, Charles Jacque, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, Constant Troyon, and Félix Ziem for $401,300.[30] In 1928 he realized $4 million for the sale of the Johnson Building, located on Exchange Street from Broad Street to New Street. He was also part of a group of investors who built the Pierre Hotel in Manhattan, which opened in 1930.[2]

After being in bad health for ten years, Billings was reported to be seriously ill on May 3, 1937,[31] and he died from pneumonia on his estate at Billings Park, near Santa Barbara, on May 6. At the time of his death, he was still the chairman of the board of the Union Carbide Carbon Company, and was described as "one of America's wealthiest men" and "Santa Barbara's wealthiest and most philanthropic citizen".[2] His funeral was held in Santa Barbara on May 8, and he was buried in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.[3]

Billings was eulogized as a modest and philanthropic man:

Personally Mr. Billings was a man of retiring, modest, nature, who shunned the limelight except when driving or riding one of his horses upon the race course, always dressed very quietly, and in every way made himself as inconspicuous as possible. He was happiest when surrounded by the small circle of intimate friends that he best-loved ... He was the loyalest of friends and when he had once given his good will to a man it was never withdrawn unless it had been abused. His benefactions and gifts were boundless and in them, he took the greatest pleasure. In all social relations he was the reverse of pompous, arrogant or domineering, was democratic and genial and, that rarest of all things—always the same admirable and wonderful character in every spot and place, at all times and seasons and under all circumstances.[3]

Legacy

- The Billings estate and mansion in Upper Manhattan was the setting for the Philo Vance mystery The Dragon Murder Case by S. S. Van Dine.[32]

- The CKG Billings Amateur Driving Series, a trotting event, is named for Billings.[33][34]

References

- ^ a b Wallace, Mike (2017), Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 468n15, ISBN 978-0-19-511635-9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Staff (May 7, 1937) "C. K. G. Billings, Noted Sportsman" (obituary) The New York Times

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hervey, John Lewis (May 12 & 19, 1937) "C. K. G. Billings: 1861 - 1937: In Memoriam" Harness Horse

- ^ a b Rush, Paul (January 11, 2009) "The Horseback Dinner" Paul Rush New York Stories

- ^ "Our History" Peoples Energy website

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Tom (October 21, 2013) "The Lost Billings Mansion -- 'Tryon Hall'" Daytonian in Manhattan

- ^ a b Staff (March 22, 1903) "The Light Harness Horse: Luxury Stables for C. K. G. Billings's Blooded Stock" The New York Times

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (July 13, 1997). "A Roadway Built for the Elite to Trot Out Their Rigs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Staff (February 6, 1894). "Cheers from the Unemployed: 1,500 Saw Mayor Gilroy Begin Work on the Speedway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Staff (July 3, 1898). "Harlem Speedway Opened; Pronounced by Horsemen to be the Finest Driveway for Light Speeding in the Country". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Robinson, Lauren (February 28, 2012). "How Harlem River Speedway Became Harlem River Drive". Museum of the City of New York.

- ^ Staff (December 4, 1919). "Autos to Use Speedway: Gallatin Will Open Harlem Drive to Passenger Machines Today". The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Rise, Decline and Fall(?) of Matinee Racing" Western Reserve Matinee Club

- ^ a b Pollak, Michael (August 15, 2004) "F.Y.I.: For an Appetizer, Hay" The New York Times

- ^ a b Bryk, William (March 30, 2005) "Banquet on Horseback" New York Sun

- ^ a b c d Staff (March 30, 1903) "Luncheon in a Stable" The New York Times

- ^ Staff (November 24, 1905) "CKG Billings Horses sold for Big Prices" The New York Times

- ^ a b Kuhn, Jonathan "Fort Tryon Park" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ a b c d Saraniero, Nicole (March 2021) "Remnants of Lost Gilded Age Billings Estate in Fort Tryon Park" Untapped New York

- ^ Ferree, Barr (1911) Fort Tryon Hall: The Residence of C. K. G. Billings, Esq.: A Descriptive and Illustrative Catalogue Issued Privately by the Owner Washington Heights, New York.

- ^ a b Vanadis" Scottish Built Shps

- ^ CORNELIUS KINGSLEY GARRISON BILLINGS & TRYON HALL, Fort Tryon Park Trust, December 5, 2017

- ^ Capraro, Douglas (June 10, 2014) "The Remains of Fort Tryon Park’s Turn of the Century Mansion Near the Cloisters" Untapped Cities

- ^ Staff (March 7, 1926) "Billings Mansion Destroyed by Fire" The New York Times

- ^ a b "'Farnsworth' The Long Island Home of C. K. G. Billings, Esq., at Locust Valley — A Country Estate in Every Respect Perfectly Appointed on The Country House website (September 27, 2013)

- ^ M/S Vanadis

- ^ Hammond, Margo (November 23, 1988). "All Aboard: Luxury Yacht Rocks Gently at Stockholm Harbor" (PDF). The Milwaukee Journal. pp. 33, 35. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Snow, Brook Hill (March 15, 1987). "Off The Beaten Path: The Lady Hutton, One Of The World's Largest Luxury Yachts, Is Now An Elegant Hotel In Downtown Stockholm". Sun Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Vanadis to Lady Hutton, Kajsa Karlsson, (1987)

- ^ Staff (1926) Famous Masterpieces of the French, Dutch, and English Schools: The Collection of C. K. G. Billings (catalog) American Art Association

- ^ Staff (May 3, 1937) "C. K. G. Billings Seriously Ill" The New York Times

- ^ Renner, James (2007) Images of America: Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5478-5

- ^ Corban, Anthony, CKG Billings Review August 2003, harnesslink.com

- ^ Knox, Tammy, Billings Amateur Trot makes stop at Hoosier Park May 2010, ustrotting.com