| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

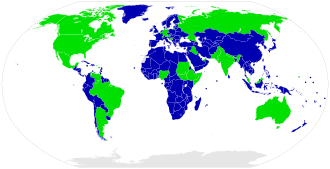

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single political system, dividing the powers between the two. Johannes Althusius is considered the father of modern federalism along with Montesquieu. He notably exposed the bases of this political philosophy in Politica Methodice Digesta, Atque Exemplis Sacris et Profanis Illustrata (1603). Montesquieu sees in the Spirit of Laws, examples of federalist republics in corporate societies, the polis bringing together villages, and the cities themselves forming confederations.[1] Federalism in the modern era was first adopted in the unions of states during the Old Swiss Confederacy.[2]

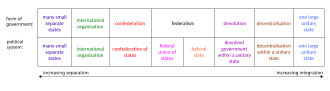

Federalism differs from confederalism, in which the general level of government is subordinate to the regional level, and from devolution within a unitary state, in which the regional level of government is subordinate to the general level.[3] It represents the central form in the pathway of regional integration or separation, bounded on the less integrated side by confederalism and on the more integrated side by devolution within a unitary state.[4][5]

Examples of a federation or federal province or state include Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Canada, Germany, India, Iraq, Malaysia, Mexico, Micronesia, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States. Some characterize the European Union as the pioneering example of federalism in a multi-state setting, in a concept termed the "federal union of states".[6][7]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:3 151 755341 20494 451108 489268 308

-

Federalism: Crash Course Government and Politics #4

-

What is federalism?

-

FEDERALISM: The Relationship Between STATES and FEDERAL Government [AP Gov Review, Unit 1 Topic 7]

-

What Is Federalism? | Things Explained

-

Federalism in the United States | US government and civics | Khan Academy

Transcription

Hi, I'm Craig and this is Crash Course Government and Politics. Today we're going to talk about a fundamental concept to American government, federalism. Sorry. I'm not sorry. You're not even endangered anymore. So federalism is a little confusing because it includes the word, "federal," as in federal government, which is what we use to describe the government of the United States as a whole. Which is kind of the opposite of what we mean when we say federalism. Confused? Google it. This video will probably come up. And then just watch this video. Or, just continue watching this video. [Intro] So what is federalism? Most simply, it's the idea that in the US, governmental power is divided between the government of the United States and the government of the individual states. The government of the US, the national government, is sometimes called the federal government, while the state governments are just called the state governments. This is because technically the US can be considered a federation of states. But this means different things to different people. For instance, federation of states means ham sandwich to me. I'll have one federation of states, please, with a side of tater tots. Thank you. I'm kind of dumb. In the federal system, the national government takes care of some things, like for example, wars with other countries and delivering the mail, while the state government takes care of other things like driver's license, hunting licenses, barber's licences, dentist's licenses, license to kill - nah, that's James Bond. And that's in England. And I hope states don't do that. Pretty simple right? Maybe not. For one thing, there are some aspects of government that are handled by both the state and national government. Taxes, American's favorite government activity, are an example. There are federal taxes and state taxes. But it gets even more complicated because there are different types of federalism depending on what period in American history you're talking about. UGH! Stan! Why is history so confusing!? UGH! Stan, are you going to tell me? Can you talk Stan? Basically though, there are two main types of federalism -dual federalism, which has nothing to do Aaron Burr, usually refers to the period of American history that stretches from the founding of our great nation until the New Deal, and cooperative federalism, which has been the rule since the 1930s. Let's start with an easy one and start with dual federalism in the Thought Bubble. From 1788 until 1937, the US basically lived under a regime of dual federalism, which meant that government power was strictly divided between the state and national governments. Notice that I didn't say separated, because I don't want you to confuse federalism with the separation of powers. DON'T DO IT! With dual federalism, there are some things that only the federal government does and some things that only the state governments do. This is sometimes called jurisdiction. The national government had jurisdiction over internal improvements like interstate roads and canals, subsidies to the states, and tariffs, which are taxes on imports and thus falls under the general heading of foreign policy. The national government also owns public lands and regulates patents which need to be national for them to offer protection for inventors in all the states. And because you want a silver dollar in Delaware to be worth the same as a silver dollar in Georgia, the national government also controls currency. The state government had control over property laws, inheritance laws, commercial laws, banking laws, corporate laws, insurance, family law, which means marriage and divorce, morality -- stuff like public nudeness and drinking - which keeps me in check -- public health, education, criminal laws including determining what is a crime and how crimes are prosecuted, land use, which includes water and mineral rights, elections, local government, and licensing of professions and occupations, basically what is required to drive a car, or open a bar or become a barber or become James Bond. So, under dual federalism, the state government has jurisdiction over a lot more than the national government. These powers over health, safety and morality are sometimes called police power and usually belong to the states. Because of the strict division between the two types of government, dual federalism is sometimes called layer cake federalism. Delicious. And it's consistent with the tradition of limited government that many Americans hold dear. Thanks Thought Bubble. Now, some of you might be wondering, Craig, where does the national government get the power to do anything that has do to with states? Yeah, well off the top of my head, the US Constitution in Article I, Section 8 Clause 3 gives Congress the power "to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes." This is what is known as the Commerce Clause, and the way that it's been interpreted is the basis of dual federalism and cooperative federalism. For most of the 19th century, the Supreme Court has decided that almost any attempt by any government, federal or state, to regulate state economic activity would violate the Commerce Clause. This basically meant that there was very little regulation of business at all. FREEDOOOOOOMM! This is how things stood, with the US following a system of dual federalism, with very little government regulation and the national government not doing much other than going to war or buying and conquering enormous amounts of territories and delivering the mail. Then the Great Depression happened, and Franklin Roosevelt and Congress enacted the New Deal, which changed the role of the federal government in a big way. The New Deal brought us cooperative federalism, where the national government encourages states and localities to pursue nationally-defined goals. The main way that the federal government does this is through dollar-dollar bills, y'all. Money is what I'm saying. Stan, can I make it rain? Yeah? Alright, I'm doing it. I happen to have cash in my hand now. Oh yeah, take my federal money, states. Regulating ya. Regulator. This money that the federal government gives to the states is called a grant-in-aid. Grants-in-aid can work like a carrot encouraging a state to adopt a certain policy or work like a stick when the federal government withholds funds if a state doesn't do what the national government wants. Grants-in-aid are usually called categorical, because they're given to states for a particular purpose like transportation or education or alleviating poverty. There are 2 types of categorical grants-in-aid: formula grants and project grants. Under a formula grant, a state gets aid in a certain amount of money based on a mathematical formula; the best example of this is the old way welfare was given in the US under the program called Aid to Families with Dependent Children. AFDC. States got a certain amount of money for every person who was classified as "poor." The more poor people a state had, the more money it got. Project grants require states to submit proposals in order to receive aid. The states compete for a limited pool of resources. Nowadays, project grants are more common than formula grants, but neither is as popular as block grants, which the government gives out Lego Blocks and then you build stuff with Legos. It's a good time. No no, the national government gives a state a huge chunk of money for something big, like infrastructure, which is made with concrete and steel, and not Legos, and the state is allowed to decide how to spend the money. The basic type of cooperative federalism is the carrot stick type which is sometimes called marble cake federalism because it mixes up the state and federal governments in ways that makes it impossible to separate the two. Federalism, it's such a culinary delight. The key to it is, you guessed it - dollar dollar bills y'all. Money. But there are another aspect of cooperative federalism that's really not so cooperative, and that's regulated federalism. Under regulated federalism, the national governments sets up regulations and rules that the states must follow. Some examples of these rules, also called mandates, are EPA regulations, civil rights standards, and the rules set up by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Sometimes the government gives the states money to implement the rules, but sometimes it doesn't and they must comply anyways. That's called an unfunded mandate. Or as I like to call it, an un-fun mandate. Because no money, no fun. A good example of example of this is OSHA regulations that employers have to follow. States don't like these, and Congress tried to do something about them with the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act or UMRA, but it hasn't really worked. In the early 21st century, Americans are basically living under a system of cooperative federalism with some areas of activity that are heavily regulated. This is a stretch from the original idea that federalism will keep the national government small and have most government functions belong to the states. If you follow American politics, and I know you do, this small government ideal should sound familiar because it's the bedrock principle of many conservatives and libertarians in the US. As conservatives made many political inroads during the 1970s, a new concept of federalism, which was kind of an old concept of federalism, became popular. It was called, SURPRISE, New Federalism, and it was popularized by Presidents Nixon and Reagan. Just to be clear, it's called New Federalism not Surprise New Federalism. New federalism basically means giving more power to the states, and this has been done in three ways. First, block grants allow states discretion to decide what to do with federal money, and what's a better way to express your power than spending money? Or not spending money as the case may be. Another form of New Federalism is devolution, which is the process of giving state and local governments the power to enforce regulations, devolving power from the national to the state level. Finally, some courts have picked up the cause of New Federalism through cases based on the 10th Amendment, which states "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." The idea that some powers, like those police powers I talked about before, are reserved by the states, have been used to put something of a brake on the Commerce Clause. So as you can see, where we are with federalism today is kind of complicated. Presidents Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Clinton seem to favor New Federalism and block grants. But George W. Bush seemed to push back towards regulated federalism with laws like No Child Left Behind and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. It's pretty safe to say that we're going to continue to live under a regime of cooperative federalism, with a healthy dose of regulation thrown in. But many Americans feel that the national government is too big and expensive and not what the framers wanted. If history is any guide, a system of dual federalism with most of the government in the hands of the states is probably not going to happen. For some reason, it's really difficult to convince institutions to give up powers once they've got them. I'm never giving up this power. Thanks for watching, I'll see you next week. Crash Course Government and Politics is produced in association with PBS Digital Studios. Support for Crash Course US Government comes from Voqal. Voqal supports non-profits that use technology and media to advance social equity. Learn more about their mission and initiatives at Voqal.org. Crash Course is made with the help of these nice people. Thanks for watching. You didn't help make this video at all, did you? No. But you did get people to keep watching until the end because you're an adorable dog.

Overview

Etymology

The terms "federalism" and "confederalism" share a root in the Latin word foedus, meaning "treaty, pact or covenant". Their common early meaning until the late eighteenth century was a simple league or inter-governmental relationship among sovereign states based on a treaty. They were therefore initially synonyms. It was in this sense that James Madison in Federalist No.39 had referred to the new US Constitution as "neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both" (i.e. as constituting neither a single large unitary state nor a league/confederation among several small states, but a hybrid of the two).[8] In the course of the nineteenth century United States, the meaning of federalism would come to shift, strengthening to refer uniquely to the novel compound political form established at the Philadelphia Convention, while the meaning of confederalism would remain at a league of states.[9]

History

In the narrow sense, federalism refers to the mode in which the body politic of a state is organized internally, and this is the meaning most often used in modern times. Political scientists, however, use it in a much broader sense, referring instead to a "multi-layer or pluralistic concept of social and political life."[10]

The first forms of federalism took place in ancient times, in the form of alliances between states. Some examples from the seventh to second century B.C. were the Archaic League, the Aetolic League, the Peloponnesian League, and the Delian League. An early ancestor of federalism was the Achaean League in Hellenistic Greece. Unlike the Greek city states of Classical Greece, each of which insisted on keeping its complete independence, changing conditions in the Hellenistic period drove many city states to band together even at the cost of losing part of their sovereignty. Subsequent unions of states included the first and second Swiss Confederations (1291–1798 and 1815–48), the United Provinces of the Netherlands (1579–1795), the German Bund (1815–66), the first American union known as the Confederation of the United States of America (1781–89), and second American union formed as the United States of America (1789–1865).[11]

Political theory

Modern federalism is a political system based upon democratic rules and institutions in which the power to govern is shared between national and provincial/state governments. The term federalist describes several political beliefs around the world depending on context. Since the term federalization also describes distinctive political processes, its use as well depends on the context.[12]

In political theory, two main types of federalization are recognized:

- integrative,[13] or aggregative federalization,[14] designating various processes like: integration of non-federated political subjects by creating a new federation, accession of non-federated subjects into an existing federation, or transformation of a confederation into a federation

- devolutive,[13] or dis-aggregative federalization:[15] transformation of a unitary state into a federation

Reasons for adoption

According to Daniel Ziblatt, there are four competing theoretical explanations in the academic literature for the adoption of federal systems:

- Ideational theories, which hold that a greater ideological commitment to decentralist ideas in society makes federalism more likely to be adopted.

- Cultural-historical theories, which hold that federal institutions are more likely to be adopted in societies with culturally or ethnically fragmented populations.

- "Social contract" theories, which hold that federalism emerges as a bargain between a center and a periphery where the center is not powerful enough to dominate the periphery and the periphery is not powerful enough to secede from the center.

- "Infrastructural power" theories, which hold that federalism is likely to emerge when the subunits of a potential federation already have highly developed infrastructures (e.g. they are already constitutional, parliamentary, and administratively modernized states).[16]

Immanuel Kant noted that "the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils" so long as they possess an appropriate constitution which pits opposing factions against each other with a system of checks and balances. In particular individual states required a federation as a safeguard against the possibility of war.[17]

Proponents for federal systems have historically argued that the power-sharing inherent in federal systems reduces both domestic security threats and foreign threats. Federalism allows states to be large and diverse, mitigating the risk of a tyrannical government through centralization of powers.[18][19]

Examples

Many countries have implemented federal systems of government with varying degree of central and regional sovereignty. The federal government of these countries can be divided into minimalistic federations, consisting of only two sub-federal units or multi-regional, those that consist of three to dozens of regional governments. They can also be grouped based on their body polity type, such as emirate, provincial, republican or state federal systems. Another way to study federated countries is by categorizing them into those whose entire territory is federated as opposed to only part of its territory comprising the federal portion of the country. Some federal systems are national systems while others, like the European Union are supra national.

In general, two extremes of federalism can be distinguished: at one extreme, the strong federal state is almost completely unitary, with few powers reserved for local governments; while at the other extreme, the national government may be a federal state in name only, being a confederation in actuality. Federalism may encompass as few as two or three internal divisions, as is the case in Belgium or Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The governments of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, India, and Mexico, among others, are also organized along federalist principles.

In Canada, federalism typically implies opposition to sovereigntist movements (most commonly Quebec separatism).[20] In 1999, the Government of Canada established the Forum of Federations as an international network for exchange of best practices among federal and federalizing countries. Headquartered in Ottawa, the Forum of Federations partner governments include Australia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan and Switzerland.

Europe vs. the United States

In Europe, "federalist" is sometimes used to describe those who favor a common federal government, with distributed power at regional, national and supranational levels. The Union of European Federalists advocates for this development within the European Union, ultimately leading to the United States of Europe.[21] Although there are medieval and early modern examples of European states which used confederal and federal systems, contemporary European federalism originated in post-war Europe; one of the more important initiatives was Winston Churchill's speech in Zürich in 1946.[22]

In the United States, federalism originally referred to belief in a stronger central government. When the U.S. Constitution was being drafted, the Federalist Party supported a stronger central government, while "Anti-Federalists" wanted a weaker central government. This is very different from the modern usage of "federalism" in Europe and the United States. The distinction stems from the fact that "federalism" is situated in the middle of the political spectrum between a confederacy and a unitary state. The U.S. Constitution was written as a replacement for the Articles of Confederation, under which the United States was a loose confederation with a weak central government.

In contrast, Europe has a greater history of unitary states than North America, thus European "federalism" argues for a weaker central government, relative to a unitary state. The modern American usage of the word is much closer to the European sense. As the power of the U.S. federal government has increased, some people[who?] have perceived a much more unitary state than they believe the Founding Fathers intended. Most people politically advocating "federalism" in the United States argue in favor of limiting the powers of the federal government, especially the judiciary (see Federalist Society, New Federalism).

The contemporary concept of federalism came about with the creation of an entirely new system of government that provided for democratic representation at two governing levels simultaneously, which was implemented in the US Constitution.[23][24] In the United States implementation of federalism, a bicameral general government, consisting of a chamber of popular representation proportional to population (the House of Representatives), and a chamber of equal State-based representation consisting of two delegates per State (the Senate), was overlaid upon the pre-existing regional governments of the thirteen independent States. With each level of government allocated a defined sphere of powers, under a written constitution and the rule of law (that is, subject to the independent third-party arbitration of a supreme court in competence disputes), the two levels were thus brought into a coordinate relationship [further explanation needed] for the first time.

In 1946, Kenneth Wheare observed that the two levels of government in the US were "co-equally supreme".[25][full citation needed] In this, he echoed the perspective of American founding father James Madison who saw the several States as forming "distinct and independent portions of the supremacy"[26] in relation to the general government.

Constitutional structure

Division of powers

In a federation, the division of power between federal and regional governments is usually outlined in the constitution. Almost every country allows some degree of regional self-government, but in federations the right to self-government of the component states is constitutionally entrenched. Component states often also possess their own constitutions which they may amend as they see fit, although in the event of conflict the federal constitution usually takes precedence.

In almost all federations the central government enjoys the powers of foreign policy and national defense as exclusive federal powers. Were this not the case a federation would not be a single sovereign state, per the UN definition. Notably, the states of Germany retain the right to act on their own behalf at an international level, a condition originally granted in exchange for the Kingdom of Bavaria's agreement to join the German Empire in 1871. The constitutions of Germany and the United States provide that all powers not specifically granted to the federal government are retained by the states. The Constitution of some countries, like Canada and India, state that powers not explicitly granted to the provincial/state governments are retained by the federal government. Much like the US system, the Australian Constitution allocates to the Federal government (the Commonwealth of Australia) the power to make laws about certain specified matters which were considered too difficult for the States to manage, so that the States retain all other areas of responsibility. Under the division of powers of the European Union in the Lisbon Treaty, powers which are not either exclusively of Union competence or shared between the Union and the Member States as concurrent powers are retained by the constituent States.

Where every component state of a federation possesses the same powers, we are said to find 'symmetric federalism'. Asymmetric federalism exists where states are granted different powers, or some possess greater autonomy than others do. This is often done in recognition of the existence of a distinct culture in a particular region or regions. In Spain, the Basques and Catalans, as well as the Galicians, spearheaded a historic movement to have their national specificity recognized, crystallizing in the "historical communities" such as Navarre, Galicia, Catalonia, and the Basque Country. They have more powers than the later expanded arrangement for other Spanish regions, or the Spain of the autonomous communities (called also the "coffee for everyone" arrangement), partly to deal with their separate identity and to appease peripheral nationalist leanings, partly out of respect to specific rights they had held earlier in history. However, strictly speaking Spain is not a federation, but a system of asymmetric devolved government within a unitary state.

It is common that during the historical evolution of a federation there is a gradual movement of power from the component states to the centre, as the federal government acquires additional powers, sometimes to deal with unforeseen circumstances. The acquisition of new powers by a federal government may occur through formal constitutional amendment or simply through a broadening of the interpretation of a government's existing constitutional powers given by the courts.

Usually, a federation is formed at two levels: the central government and the regions (states, provinces, territories), and little to nothing is said about second or third level administrative political entities. Brazil is an exception, because the 1988 Constitution included the municipalities as autonomous political entities making the federation tripartite, encompassing the Union, the States, and the municipalities. Each state is divided into municipalities (municípios) with their own legislative council (câmara de vereadores) and a mayor (prefeito), which are partly autonomous from both Federal and State Government. Each municipality has a "little constitution", called "organic law" (lei orgânica). Mexico is an intermediate case, in that municipalities are granted full-autonomy by the federal constitution and their existence as autonomous entities (municipio libre, "free municipality") is established by the federal government and cannot be revoked by the states' constitutions. Moreover, the federal constitution determines which powers and competencies belong exclusively to the municipalities and not to the constituent states. However, municipalities do not have an elected legislative assembly.

Federations often employ the paradox of being a union of states, while still being states (or having aspects of statehood) in themselves. For example, James Madison (author of the United States Constitution) wrote in Federalist Paper No. 39 that the US Constitution "is in strictness neither a national nor a federal constitution; but a composition of both. In its foundation, it is federal, not national; in the sources from which the ordinary powers of the Government are drawn, it is partly federal, and partly national..." This stems from the fact that states in the US maintain all sovereignty that they do not yield to the federation by their own consent. This was reaffirmed by the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which reserves all powers and rights that are not delegated to the Federal Government as left to the States and to the people.

Bicameralism

The structures of most federal governments incorporate mechanisms to protect the rights of component states. One method, known as 'intrastate federalism', is to directly represent the governments of component states in federal political institutions. Where a federation has a bicameral legislature the upper house is often used to represent the component states while the lower house represents the people of the nation as a whole. A federal upper house may be based on a special scheme of apportionment, as is the case in the senates of the United States and Australia, where each state is represented by an equal number of senators irrespective of the size of its population.

Alternatively, or in addition to this practice, the members of an upper house may be indirectly elected by the government or legislature of the component states, as occurred in the United States prior to 1913, or be actual members or delegates of the state governments, as, for example, is the case in the German Bundesrat and in the Council of the European Union. The lower house of a federal legislature is usually directly elected, with apportionment in proportion to population, although states may sometimes still be guaranteed a certain minimum number of seats.

Intergovernmental relations

In Canada, the provincial governments represent regional interests and negotiate directly with the central government. A First Ministers conference of the prime minister and the provincial premiers is the de facto highest political forum in the land, although it is not mentioned in the constitution.

Constitutional change

Federations often have special procedures for amendment of the federal constitution. As well as reflecting the federal structure of the state this may guarantee that the self-governing status of the component states cannot be abolished without their consent. An amendment to the constitution of the United States must be ratified by three-quarters of either the state legislatures, or of constitutional conventions specially elected in each of the states, before it can come into effect. In referendums to amend the constitutions of Australia and Switzerland it is required that a proposal be endorsed not just by an overall majority of the electorate in the nation as a whole, but also by separate majorities in each of a majority of the states or cantons. In Australia, this latter requirement is known as a double majority.

Some federal constitutions also provide that certain constitutional amendments cannot occur without the unanimous consent of all states or of a particular state. The US constitution provides that no state may be deprived of equal representation in the senate without its consent. In Australia, if a proposed amendment will specifically impact one or more states, then it must be endorsed in the referendum held in each of those states. Any amendment to the Canadian constitution that would modify the role of the monarchy would require unanimous consent of the provinces. The German Basic Law provides that no amendment is admissible at all that would abolish the federal system.

Other technical terms

- Fiscal federalism – the relative financial positions and the financial relations between the levels of government in a federal system.

- Formal federalism (or 'constitutional federalism') – the delineation of powers is specified in a written constitution, which may or may not correspond to the actual operation of the system in practice.

- Executive federalism refers in the English-speaking tradition to the intergovernmental relationships between the executive branches of the levels of government in a federal system and in the continental European tradition to the way constituent units 'execute' or administer laws made centrally.

- Gleichschaltung – the conversion from a federal governance to either a completely unitary or more unitary one, the term was borrowed from the German for conversion from alternating to direct current.[27] During the Nazi era the traditional German states were mostly left intact in the formal sense, but their constitutional rights and sovereignty were eroded and ultimately ended and replaced with the Gau system. Gleichschaltung also has a broader sense referring to political consolidation in general.

- defederalize – to remove from federal government, such as taking a responsibility from a national level government and giving it to states or provinces

In relation to conflict

It has been argued that federalism and other forms of territorial autonomy are a useful way to structure political systems in order to prevent violence among different groups within countries because it allows certain groups to legislate at the subnational level.[28] Some scholars have suggested, however, that federalism can divide countries and result in state collapse because it creates proto-states.[29] Still others have shown that federalism is only divisive when it lacks mechanisms that encourage political parties to compete across regional boundaries.[30]

Federalism is sometimes viewed in the context of international negotiation as "the best system for integrating diverse nations, ethnic groups, or combatant parties, all of whom may have cause to fear control by an overly powerful center."[31] However, those skeptical of federal prescriptions sometimes believe that increased regional autonomy can lead to secession or dissolution of the nation.[31] In Syria, for example, federalization proposals have failed in part because "Syrians fear that these borders could turn out to be the same as the ones that the fighting parties have currently carved out."[31]

See also

- Bibliography of the United States Constitution

- Commonwealth – Term for a political community founded for the common good

- Consociationalism – Political power sharing among cultural groups

- Cooperative federalism – Flexible government where state and national level cooperate

- Democratic World Federalists

- Feudalism – Legal and military structure in medieval Europe

- Neo-feudalism – Theoretic rebirth of antique governance

- Federal republicanism – 1873–1874 republican government

- Federal Union – Pro-European British political group

- Forum of Federations – bilateral relations

- Layer cake federalism – Political arrangement

- Non-governmental federation – Federations which are not states or national governments

- Pillarisation – Division of civil society along religiopolitical lines

- States' rights – Political powers reserved for US states

- Union of Utrecht – 1579 treaty unifying the northern Netherlands provinces

- World Federalist Movement – Political idea of a global federal government

Notes and references

- ^ Johannes Althusius, On Law and Power Archived 2016-08-14 at the Wayback Machine. CLP Academic, 2013, p.xx.

- ^ Forsyth 1981, p. 18.

- ^ Wheare 1946, pp. 31–22.

- ^ See diagram below.

- ^ Diamond, Martin (1961) "The Federalist's View of Federalism", in Benson, George (ed.) Essays in Federalism, Institute for Studies in Federalism, Claremont, p. 22. Downs, William (2011) "Comparative Federalism, Confederalism, Unitary Systems", in Ishiyama, John and Breuning, Marijke (eds) Twenty-first Century Political Science: A Reference Handbook, Sage, Los Angeles, Vol. I, pp. 168–170. Hueglin, Thomas and Fenna, Alan (2006) Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry, Broadview, Peterborough, p. 31.

- ^ See Law, John (2013), p. 104. http://www.on-federalism.eu/attachments/169_download.pdf Archived 2015-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

This author identifies two distinct federal forms, where before only one was known, based upon whether sovereignty (conceived in its core meaning of ultimate authority) resides in the whole (in one people) or in the parts (in many peoples). This is determined by the absence or presence of a unilateral right of secession for the parts. The structures are termed, respectively, the federal state (or federation) and the federal union of states (or federal union). - ^ Usherwood, Simon; Pinder, John (2018-01-25). "The European Union: A Very Short Introduction". Very Short Introductions. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780198808855.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-880885-5.

- ^ Madison, James, Hamilton, Alexander and Jay, John (1987) The Federalist Papers, Penguin, Harmondsworth, p. 259.

- ^ Law, John (2012) "Sense on Federalism", in Political Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 3, p. 544.

- ^ Bulmer, Elliot. "Federalism" (PDF). International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 12: 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-28.

- ^ Forsyth 1981, pp. 18, 25, 30, 43, 53, 60.

- ^ Broschek 2016, p. 23–50.

- ^ a b Gerven 2005, p. 35, 392.

- ^ Broschek 2016, pp. 27–28, 39.

- ^ Broschek 2016, pp. 27–28, 39–41, 44.

- ^ Ziblatt, Daniel (2008). Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691136493. Archived from the original on 2017-03-07. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ^ Reiss, H.S. (2013). Kant: Political Writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107268364. Archived from the original on 2023-07-31. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Deudney, Daniel H. (2007). Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3727-4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-31. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ Deudney, Daniel (2004). "Publius Before Kant: Federal-Republican Security and Democratic Peace". European Journal of International Relations. 10 (3): 315–356. doi:10.1177/1354066104045540. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 143608840. Archived from the original on 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ "CBC on Federalism and Separatism". Archived from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "70_Years_of_Campaigns_for_a_United_and_Federal_Europe" (PDF). www.federalists.eu. Union of European Federalists. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-28.

- ^ "The Churchill Society London. Churchill's Speeches". www.churchill-society-london.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ Law, John (2012) "Sense on Federalism", in Political Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 3, pp. 543–544.

- ^ Wheare 1946, p. 11.

- ^ Wheare 1946, pp. 10–15.

- ^ Madison, James, Hamilton, Alexander and Jay, John (1987) The Federalist Papers, Penguin, Harmondsworth, p. 258.

- ^ Koonz, Claudia (2003). The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-674-01172-4.

- ^ Lijphart, Arend (1977). Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ Hale, Henry E. (2004). "Divided We Stand: Institutional Sources of Ethnofederal State Survival and Collapse". World Politics. 56 (2): 165–193. doi:10.1353/wp.2004.0011. ISSN 1086-3338. S2CID 155052031.

- ^ Dawn Brancati. 2009. Peace by Design: Managing Intrastate Conflict through Decentralization. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- ^ a b c Michael Meyer-Resende, "Why Talk of Federalism Won't Help Peace in Syria", Foreign Policy (March 18, 2017). Archived 2017-03-15 at the Wayback Machine.

Sources

- Bednar, Jenna (2011). "The Political Science of Federalism". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 7: 269–288. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105522.

- Broschek, Jorg (2016). "Federalism in Europe, America and Africa: A Comparative Analysis". Federalism and Decentralization: Perceptions for Political and Institutional Reforms (PDF). Singapore: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. pp. 23–50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-20.

- Forsyth, Murray (1981). Unions of States: The Theory and Practice of Confederation. Leicester University Press. OCLC 1170233780.

- Gerven, Walter van (2005). The European Union: A Polity of States and Peoples. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804750646. Archived from the original on 2023-07-31. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Wheare, Kenneth (1946). Federal Government. London: Oxford University Press.

External links

- P.-J. Proudhon (1863), The Principle of Federation.