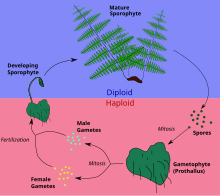

Alternation of generations (also known as metagenesis or heterogenesis)[1] is the predominant type of life cycle in plants and algae. In plants both phases are multicellular: the haploid sexual phase – the gametophyte – alternates with a diploid asexual phase – the sporophyte.

A mature sporophyte produces haploid spores by meiosis, a process which reduces the number of chromosomes to half, from two sets to one. The resulting haploid spores germinate and grow into multicellular haploid gametophytes. At maturity, a gametophyte produces gametes by mitosis, the normal process of cell division in eukaryotes, which maintains the original number of chromosomes. Two haploid gametes (originating from different organisms of the same species or from the same organism) fuse to produce a diploid zygote, which divides repeatedly by mitosis, developing into a multicellular diploid sporophyte. This cycle, from gametophyte to sporophyte (or equally from sporophyte to gametophyte), is the way in which all land plants and most algae undergo sexual reproduction.

The relationship between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases varies among different groups of plants. In the majority of algae, the sporophyte and gametophyte are separate independent organisms, which may or may not have a similar appearance. In liverworts, mosses and hornworts, the sporophyte is less well developed than the gametophyte and is largely dependent on it. Although moss and hornwort sporophytes can photosynthesise, they require additional photosynthate from the gametophyte to sustain growth and spore development and depend on it for supply of water, mineral nutrients and nitrogen.[2][3] By contrast, in all modern vascular plants the gametophyte is less well developed than the sporophyte, although their Devonian ancestors had gametophytes and sporophytes of approximately equivalent complexity.[4] In ferns the gametophyte is a small flattened autotrophic prothallus on which the young sporophyte is briefly dependent for its nutrition. In flowering plants, the reduction of the gametophyte is much more extreme; it consists of just a few cells which grow entirely inside the sporophyte.

Animals develop differently. They directly produce haploid gametes. No haploid spores capable of dividing are produced, so generally there is no multicellular haploid phase. Some insects have a sex-determining system whereby haploid males are produced from unfertilized eggs; however females produced from fertilized eggs are diploid.

Life cycles of plants and algae with alternating haploid and diploid multicellular stages are referred to as diplohaplontic. The equivalent terms haplodiplontic, diplobiontic and dibiontic are also in use, as is describing such an organism as having a diphasic ontogeny.[5] Life cycles of animals, in which there is only a diploid multicellular stage, are referred to as diplontic. Life cycles in which there is only a haploid multicellular stage are referred to as haplontic.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:893 60699 91054 99672 829114 244

-

The Reproductive Lives of Nonvascular Plants: Alternation of Generations - Crash Course Biology #36

-

On Alternation of Generations

-

Alternation of Generations

-

5 Minute Trick to Learn Alternation of Generation in Plants | Concept & Examples | ft. Vipin Sharma

-

Alternation of Generations Life Cycle

Transcription

Plants! You're familiar with their work: They turn all that carbon dioxide that we don't want into the oxygen we do want, they're all around us, and they've been around for a lot longer than animals. The plants that we see today probably evolved from a single species of algae that noodged itself onshore about 1.2 billion years ago. And from that one little piece of algae, all of the half million or so species of plants that we have today evolved. But of course all this didn't happen overnight. It wasn't until about 475 million years ago that the first plants started to evolve. And they were very simple didn't have a lot of different tissue types, and the descendants of those plants still live among us today. They're the nonvascular plants: the liverworts, the hornworts and everybody's best friends, the mosses. Mmm, fuzzy! Now, yeah, it's clear that these guys are less complicated than an orchid or an oak tree, and if you said they were less beautiful, you probably wouldn't get that much argument from me. But by now I think you've learned enough about biology to know that when it comes to the simplest things: sometimes they're the craziest of all. Because they evolved early in the scheme of things they were sort of able to evolve their own set of rules. So, much like we saw with archaea, protists and bacteria, nonvascular plants have some bizarre features and some kooky habits that seem, to us, like, kind of, just, like, what? Especially when it comes to their sex lives. The main thing to know about nonvascular plants is their reproductive cycle, which they inherited from algae but perfected to the point where now it is used by all plants in one way or another, and there are even traces of it in our own reproductive systems. Usually when we're talking about plants, we're really talking about vascular plants, which have stuff like roots, stems, and leaves. Those roots, stems and leaves are actually tissues that transport water and nutrients from one part of the plant to another. As a result, vascular plants are able to go all giant sequoia. The main defining trait of nonvascular plants is that they don't have specialized conductive tissues. Since they don't have roots and stems, they can't reach down into the soil to get to water and nutrients. They have to take moisture in directly through their cell walls and move it around from cell to cell through osmosis, while they rely on diffusion to transport minerals. Another thing nonvascular plants have in common is limited growth potential. Largely because they don't have tissues to move the good stuff around, or woody tissue to support more mass, the way for them to win is to keep it simple and small. So small that when you look at one of these dudes, you sometimes might not know what you're looking at. And finally, nonvascular plants need water for reproduction This is kind of a bummer for them because it means they can't really survive in dry places like a lot of vascular plants can. But I'll get back to that in a minute. Other than that, nonvasculars are true plants: They're multicellular, they have cell walls made of cellulose, and they use photosynthesis to make their food. All the nonvascular plants are collectively referred to as bryophytes, and who knows how many different sorts there used to be back in the olden days, but we can currently meet three phyla of bryophytes in person: the mosses, in phylum Bryophyta, the liverworts, in phylum Hepatophyta, and the hornworts in phylum Anthocerophyta. Taken together, there are over 24,000 species of bryophytes out there: about 15,000 are mosses, 9,000 are liverworts and only only about 100 are hornworts. Hornworts and liverworts, funny names, but are named after the shape of their leaf-like structures horns for the hornworts and livers for the liverworts with "wort," stuck on the end there, which just means "herb." And you know what moss looks like, though some things that are called moss like "Spanish moss" in the southern United States, and "reindeer moss" up in the alpine tundra of Alaska, are imposters, they're actually lichens and lichens aren't even plants! The very oldest fossils of plant fragments look really similar to liverworts, but nobody really knows which of the bryophytes evolved first and which descended from which. We just know that something very bryophytic-looking was the first plant to rear its leafy head back in the Ordovician swamps. So, now we've got these ultra-old timey nonvascular plants to provide us with some clues as to how plants evolved. And like I mentioned, the most important contribution to the Kingdom Plantae, and everything that came after them, is their wonderfully complex reproductive cycle. See, plants, vascular and nonvascular, have a way more complicated sexual life cycle than animals do. With animals, it's pretty much a one-step process: two haploid gametes, one from the mom and one from the dad, come together to make a diploid cell that combines the genetic material from both parents. That diploid cell divides and divides and divides and divides until, voila! The world is one marmot or grasshopper richer. Plants, on the other hand, along with algae and a handful of invertebrate animal species, have evolved a cycle in which they take on two different forms over the course of their lives, one form giving rise to the other form. This type of reproductive cycle is called alternation of generations, and it evolved first in algae, and many of them still use it today. However, the difference between algae and plants here is that, in algae, both generations look pretty much the same, while in land plants, all land plants, the alternating generations are fundamentally different from each other. And by fundamental, I mean that the two don't even share the same basic reproductive strategy. One generation, called the gametophyte, reproduces sexually by producing gametes, eggs and sperm, which you know are haploid cells that only carry one set of chromosomes. And the bryophyte sperm is a lot like human sperm, except they have two flagella instead of one, and they're kind of coil shaped. When the sperm and egg fuse, they give rise to the second generation, called the sporophyte generation, which is asexual. The sporophyte itself is diploid, so it already has two sets of chromosomes in each cell. It has a little capsule called a sporangium, which produces haploid reproductive cells called spores. During its life, the sporophyte remains attached to its parent gametophyte, which it relies on for water and nutrients. Once its spores disperse and germinate, they in turn produce gametophytes, which turn around and produce another sporophyte generation. And so on. Weird, I know, but that's the fun of it. Life is peculiar and that's what makes it so great. This means that the nonvascular plants that we all recognize, the green, leafy, livery or horny parts of the moss, liverwort or hornwort, are actually gametophytes. Sporophytes are only found tucked inside the females, and they're super small and hard to see. So in this gametophyte generation, individuals are always either male or female. The male makes sperm through mitosis in a feature called the antheridia, the male reproductive structure. While the female gametophyte makes the egg, also through mitosis, inside the female reproductive structures, which are called the archegonia. These two gametophytes might be hanging out right next to each other, sperm and eggs totally ready to go, but they can't do anything until water is introduced to the situation. So let's just add a sprinkle of water and take a tour of the bryophytes' sex cycle, shall we? By way of the water, the sperm finds its way to the female and then into the egg, where the two gametes fuse to create a diploid zygote, which divides by mitosis and grows into a sporophyte. The sporophyte grows inside the mother, until one day it cracks open and the sporophyte sends up a long stalk with a little cap on top called the calyptra. This protective case is made out of the remaining piece of the mother gametophyte, and under it a capsule forms full of thousands of little diploid spores. When the capsule is mature, the lid falls off, and the spores are exposed to the air. If humidity levels are high enough, the capsule will let the spores go to meet their fate. Now, if one lands on a basketball court or something, it will just die if it doesn't get water. But if it lands on moist ground, it germinates, producing a little filament called the protonema, that gives rise to buds. These eventually grow into a patch of moss, which is just a colony of haploid gametophytes. That generation will mate, and make sporophytes, and the generations will continue their alternation indefinitely! Now because nonvascular plants are the least complex kind of plants, their alternation of generations process is about as simple as it gets. But with vascular plants, because they have all kinds of specialized tissues, things get a little more convoluted. For instance, plants that produce unprotected seeds, like conifers or gingko trees, are gymnosperms, and it's at this level that we start to see pollen, which is just a male gamete that can float through the air. The pollen thing is taken to the next level with angiosperms, or flowering plants, which are the most diverse group of land plants, and the most recently evolved. So the main difference between the alternation of generations in vascular and nonvascular plants is that in bryophytes you recognize the gametophyte as being the... you know, the plant part. The moss or the liverwort or whatever. While the sporophyte is less recognizable and smaller. But as plants get more complicated, like with vascular plants, the sporophytes become the dominant phase, more prominent or recognizable. Like the flower of an angiosperm, for instance, is, itself, actually the sporophyte. Now I maybe just stuck a spoon in all the stuff that you learned and stirred it up to confuse you more. But we'll get into this more when we talk about the reproduction of vascular plants. But whether they have a big showy sporophyte like a flower or a little, damp gametophyte like a moss, all land plants came from the same, tiny little ancient nonvascular plant who just put their sperm out there, hoping to find some lady gametophyte they could call their own. And I think that's kind of sweet. Thank you for watching this episode of Crash Course Biology. And thanks to all the people who helped put it together. There's a table of contents over there if you want to go review anything. And if you have any questions for us, we're on Facebook and Twitter and, of course, we're down in the comments below. Thanks a lot.

Definition

Alternation of generations is defined as the alternation of multicellular diploid and haploid forms in the organism's life cycle, regardless of whether these forms are free-living.[6] In some species, such as the alga Ulva lactuca, the diploid and haploid forms are indeed both free-living independent organisms, essentially identical in appearance and therefore said to be isomorphic. In many algae, the free-swimming, haploid gametes form a diploid zygote which germinates into a multicellular diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte produces free-swimming haploid spores by meiosis that germinate into haploid gametophytes.[7]

However, in land plants, either the sporophyte or the gametophyte is very much reduced and is incapable of free living. For example, in all bryophytes the gametophyte generation is dominant and the sporophyte is dependent on it. By contrast, in all seed plants the gametophytes are strongly reduced, although the fossil evidence indicates that they were derived from isomorphic ancestors.[4] In seed plants, the female gametophyte develops totally within the sporophyte, which protects and nurtures it and the embryonic sporophyte that it produces. The pollen grains, which are the male gametophytes, are reduced to only a few cells (just three cells in many cases). Here the notion of two generations is less obvious; as Bateman & Dimichele say "sporophyte and gametophyte effectively function as a single organism".[8] The alternative term 'alternation of phases' may then be more appropriate.[9]

History

Debates about alternation of generations in the early twentieth century can be confusing because various ways of classifying "generations" co-exist (sexual vs. asexual, gametophyte vs. sporophyte, haploid vs. diploid, etc.).[10]

Initially, Chamisso and Steenstrup described the succession of differently organized generations (sexual and asexual) in animals as "alternation of generations", while studying the development of tunicates, cnidarians and trematode animals.[10] This phenomenon is also known as heterogamy. Presently, the term "alternation of generations" is almost exclusively associated with the life cycles of plants, specifically with the alternation of haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes.[10]

Wilhelm Hofmeister demonstrated the morphological alternation of generations in plants,[11] between a spore-bearing generation (sporophyte) and a gamete-bearing generation (gametophyte).[12][13] By that time, a debate emerged focusing on the origin of the asexual generation of land plants (i.e., the sporophyte) and is conventionally characterized as a conflict between theories of antithetic (Čelakovský, 1874) and homologous (Pringsheim, 1876) alternation of generations.[10] Čelakovský coined the words sporophyte and gametophyte.[citation needed]

Eduard Strasburger (1874) discovered the alternation between diploid and haploid nuclear phases,[10] also called cytological alternation of nuclear phases.[14] Although most often coinciding, morphological alternation and nuclear phases alternation are sometimes independent of one another, e.g., in many red algae, the same nuclear phase may correspond to two diverse morphological generations.[14] In some ferns which lost sexual reproduction, there is no change in nuclear phase, but the alternation of generations is maintained.[15]

Alternation of generations in plants

Fundamental elements

The diagram above shows the fundamental elements of the alternation of generations in plants. There are many variations in different groups of plants. The processes involved are as follows:[16]

- Two single-celled haploid gametes, each containing n unpaired chromosomes, fuse to form a single-celled diploid zygote, which now contains n pairs of chromosomes, i.e. 2n chromosomes in total.[16]

- The single-celled diploid zygote germinates, dividing by the normal process (mitosis), which maintains the number of chromosomes at 2n. The result is a multi-cellular diploid organism, called the sporophyte (because at maturity it produces spores).[16]

- When it reaches maturity, the sporophyte produces one or more sporangia (singular: sporangium) which are the organs that produce diploid spore mother cells (sporocytes). These divide by a special process (meiosis) that reduces the number of chromosomes by a half. This initially results in four single-celled haploid spores, each containing n unpaired chromosomes.[16]

- The single-celled haploid spore germinates, dividing by the normal process (mitosis), which maintains the number of chromosomes at n. The result is a multi-cellular haploid organism, called the gametophyte (because it produces gametes at maturity).[16]

- When it reaches maturity, the gametophyte produces one or more gametangia (singular: gametangium) which are the organs that produce haploid gametes. At least one kind of gamete possesses some mechanism for reaching another gamete in order to fuse with it.[16]

The 'alternation of generations' in the life cycle is thus between a diploid (2n) generation of multicellular sporophytes and a haploid (n) generation of multicellular gametophytes.[16]

The situation is quite different from that in animals, where the fundamental process is that a multicellular diploid (2n) individual directly produces haploid (n) gametes by meiosis. In animals, spores (i.e. haploid cells which are able to undergo mitosis) are not produced, so there is no asexual multicellular generation. Some insects have haploid males that develop from unfertilized eggs, but the females are all diploid.[16]

Variations

The diagram shown above is a good representation of the life cycle of some multi-cellular algae (e.g. the genus Cladophora) which have sporophytes and gametophytes of almost identical appearance and which do not have different kinds of spores or gametes.[17]

However, there are many possible variations on the fundamental elements of a life cycle which has alternation of generations. Each variation may occur separately or in combination, resulting in a bewildering variety of life cycles. The terms used by botanists in describing these life cycles can be equally bewildering. As Bateman and Dimichele say "[...] the alternation of generations has become a terminological morass; often, one term represents several concepts or one concept is represented by several terms."[18]

Possible variations are:

- Relative importance of the sporophyte and the gametophyte.

- Equal (homomorphy or isomorphy).

Filamentous algae of the genus Cladophora, which are predominantly found in fresh water, have diploid sporophytes and haploid gametophytes which are externally indistinguishable.[19] No living land plant has equally dominant sporophytes and gametophytes, although some theories of the evolution of alternation of generations suggest that ancestral land plants did. - Unequal (heteromorphy or anisomorphy).

Gametophyte of Mnium hornum, a moss. - Dominant gametophyte (gametophytic).

In liverworts, mosses and hornworts, the dominant form is the haploid gametophyte. The diploid sporophyte is not capable of an independent existence, gaining most of its nutrition from the parent gametophyte, and having no chlorophyll when mature.[20]

Sporophyte of Lomaria discolor, a fern. - Dominant sporophyte (sporophytic).

In ferns, both the sporophyte and the gametophyte are capable of living independently, but the dominant form is the diploid sporophyte. The haploid gametophyte is much smaller and simpler in structure. In seed plants, the gametophyte is even more reduced (at the minimum to only three cells), gaining all its nutrition from the sporophyte. The extreme reduction in the size of the gametophyte and its retention within the sporophyte means that when applied to seed plants the term 'alternation of generations' is somewhat misleading: "[s]porophyte and gametophyte effectively function as a single organism".[8] Some authors have preferred the term 'alternation of phases'.[9]

- Dominant gametophyte (gametophytic).

- Equal (homomorphy or isomorphy).

- Differentiation of the gametes.

- Both gametes the same (isogamy).

Like other species of Cladophora, C. callicoma has flagellated gametes which are identical in appearance and ability to move.[19] - Gametes of two distinct sizes (anisogamy).

- Both of similar motility.

Species of Ulva, the sea lettuce, have gametes which all have two flagella and so are motile. However they are of two sizes: larger 'female' gametes and smaller 'male' gametes.[21] - One large and sessile, one small and motile (oogamy). The larger sessile megagametes are eggs (ova), and smaller motile microgametes are sperm (spermatozoa, spermatozoids). The degree of motility of the sperm may be very limited (as in the case of flowering plants) but all are able to move towards the sessile eggs. When (as is almost always the case) the sperm and eggs are produced in different kinds of gametangia, the sperm-producing ones are called antheridia (singular antheridium) and the egg-producing ones archegonia (singular archegonium).

Gametophyte of Pellia epiphylla with sporophytes growing from the remains of archegonia. - Antheridia and archegonia occur on the same gametophyte, which is then called monoicous. (Many sources, including those concerned with bryophytes, use the term 'monoecious' for this situation and 'dioecious' for the opposite.[22][23] Here 'monoecious' and 'dioecious' are used only for sporophytes.)

The liverwort Pellia epiphylla has the gametophyte as the dominant generation. It is monoicous: the small reddish sperm-producing antheridia are scattered along the midrib while the egg-producing archegonia grow nearer the tips of divisions of the plant.[24] - Antheridia and archegonia occur on different gametophytes, which are then called dioicous.

The moss Mnium hornum has the gametophyte as the dominant generation. It is dioicous: male plants produce only antheridia in terminal rosettes, female plants produce only archegonia in the form of stalked capsules.[25] Seed plant gametophytes are also dioicous. However, the parent sporophyte may be monoecious, producing both male and female gametophytes or dioecious, producing gametophytes of one gender only. Seed plant gametophytes are extremely reduced in size; the archegonium consists only of a small number of cells, and the entire male gametophyte may be represented by only two cells.[26]

- Antheridia and archegonia occur on the same gametophyte, which is then called monoicous. (Many sources, including those concerned with bryophytes, use the term 'monoecious' for this situation and 'dioecious' for the opposite.[22][23] Here 'monoecious' and 'dioecious' are used only for sporophytes.)

- Both of similar motility.

- Both gametes the same (isogamy).

- Differentiation of the spores.

- All spores the same size (homospory or isospory).

Horsetails (species of Equisetum) have spores which are all of the same size.[27] - Spores of two distinct sizes (heterospory or anisospory): larger megaspores and smaller microspores. When the two kinds of spore are produced in different kinds of sporangia, these are called megasporangia and microsporangia. A megaspore often (but not always) develops at the expense of the other three cells resulting from meiosis, which abort.

- Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on the same sporophyte, which is then called monoecious.

Most flowering plants fall into this category. Thus the flower of a lily contains six stamens (the microsporangia) which produce microspores which develop into pollen grains (the microgametophytes), and three fused carpels which produce integumented megasporangia (ovules) each of which produces a megaspore which develops inside the megasporangium to produce the megagametophyte. In other plants, such as hazel, some flowers have only stamens, others only carpels, but the same plant (i.e. sporophyte) has both kinds of flower and so is monoecious.

Flowers of European holly, a dioecious species: male above, female below (leaves cut to show flowers more clearly) - Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on different sporophytes, which are then called dioecious.

An individual tree of the European holly (Ilex aquifolium) produces either 'male' flowers which have only functional stamens (microsporangia) producing microspores which develop into pollen grains (microgametophytes) or 'female' flowers which have only functional carpels producing integumented megasporangia (ovules) that contain a megaspore that develops into a multicellular megagametophyte.

- Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on the same sporophyte, which is then called monoecious.

- All spores the same size (homospory or isospory).

There are some correlations between these variations, but they are just that, correlations, and not absolute. For example, in flowering plants, microspores ultimately produce microgametes (sperm) and megaspores ultimately produce megagametes (eggs). However, in ferns and their allies there are groups with undifferentiated spores but differentiated gametophytes. For example, the fern Ceratopteris thalictrioides has spores of only one kind, which vary continuously in size. Smaller spores tend to germinate into gametophytes which produce only sperm-producing antheridia.[27]

A complex life cycle

Plant life cycles can be complex. Alternation of generations can take place in plants which are at once heteromorphic, sporophytic, oogametic, dioicous, heterosporic and dioecious, such as in a willow tree (as most species of the genus Salix are dioecious).[28] The processes involved are:

- An immobile egg, contained in the archegonium, fuses with a mobile sperm, released from an antheridium. The resulting zygote is either 'male' or 'female'.

- A 'male' zygote develops by mitosis into a microsporophyte, which at maturity produces one or more microsporangia. Microspores develop within the microsporangium by meiosis.

In a willow (like all seed plants) the zygote first develops into an embryo microsporophyte within the ovule (a megasporangium enclosed in one or more protective layers of tissue known as integument). At maturity, these structures become the seed. Later the seed is shed, germinates and grows into a mature tree. A 'male' willow tree (a microsporophyte) produces flowers with only stamens, the anthers of which are the microsporangia. - Microspores germinate producing microgametophytes; at maturity one or more antheridia are produced. Sperm develop within the antheridia.

In a willow, microspores are not liberated from the anther (the microsporangium), but develop into pollen grains (microgametophytes) within it. The whole pollen grain is moved (e.g. by an insect or by the wind) to an ovule (megagametophyte), where a sperm is produced which moves down a pollen tube to reach the egg. - A 'female' zygote develops by mitosis into a megasporophyte, which at maturity produces one or more megasporangia. Megaspores develop within the megasporangium; typically one of the four spores produced by meiosis gains bulk at the expense of the remaining three, which disappear.

'Female' willow trees (megasporophytes) produce flowers with only carpels (modified leaves that bear the megasporangia). - Megaspores germinate producing megagametophytes; at maturity one or more archegonia are produced. Eggs develop within the archegonia.

The carpels of a willow produce ovules, megasporangia enclosed in integuments. Within each ovule, a megaspore develops by mitosis into a megagametophyte. An archegonium develops within the megagametophyte and produces an egg. The whole of the gametophytic 'generation' remains within the protection of the sporophyte except for pollen grains (which have been reduced to just three cells contained within the microspore wall).

- A 'male' zygote develops by mitosis into a microsporophyte, which at maturity produces one or more microsporangia. Microspores develop within the microsporangium by meiosis.

Life cycles of different plant groups

The term "plants" is taken here to mean the Archaeplastida, i.e. the glaucophytes, red and green algae and land plants.

Alternation of generations occurs in almost all multicellular red and green algae, both freshwater forms (such as Cladophora) and seaweeds (such as Ulva). In most, the generations are homomorphic (isomorphic) and free-living. Some species of red algae have a complex triphasic alternation of generations, in which there is a gametophyte phase and two distinct sporophyte phases. For further information, see Red algae: Reproduction.

Land plants all have heteromorphic (anisomorphic) alternation of generations, in which the sporophyte and gametophyte are distinctly different. All bryophytes, i.e. liverworts, mosses and hornworts, have the gametophyte generation as the most conspicuous. As an illustration, consider a monoicous moss. Antheridia and archegonia develop on the mature plant (the gametophyte). In the presence of water, the biflagellate sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia and fertilisation occurs, leading to the production of a diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte grows up from the archegonium. Its body comprises a long stalk topped by a capsule within which spore-producing cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. Most mosses rely on the wind to disperse these spores, although Splachnum sphaericum is entomophilous, recruiting insects to disperse its spores.

-

Alternation of generations in liverworts

-

Moss life cycle

-

Hornwort life cycle

The life cycle of ferns and their allies, including clubmosses and horsetails, the conspicuous plant observed in the field is the diploid sporophyte. The haploid spores develop in sori on the underside of the fronds and are dispersed by the wind (or in some cases, by floating on water). If conditions are right, a spore will germinate and grow into a rather inconspicuous plant body called a prothallus. The haploid prothallus does not resemble the sporophyte, and as such ferns and their allies have a heteromorphic alternation of generations. The prothallus is short-lived, but carries out sexual reproduction, producing the diploid zygote that then grows out of the prothallus as the sporophyte.

-

Alternation of generations in ferns

-

A gametophyte (prothallus) of Dicksonia

-

A sporophyte of Dicksonia antarctica

-

Dicksonia antarctica frond with spore-producing structures

In the spermatophytes, the seed plants, the sporophyte is the dominant multicellular phase; the gametophytes are strongly reduced in size and very different in morphology. The entire gametophyte generation, with the sole exception of pollen grains (microgametophytes), is contained within the sporophyte. The life cycle of a dioecious flowering plant (angiosperm), the willow, has been outlined in some detail in an earlier section (A complex life cycle). The life cycle of a gymnosperm is similar. However, flowering plants have in addition a phenomenon called 'double fertilization'. In the process of double fertilization, two sperm nuclei from a pollen grain (the microgametophyte), rather than a single sperm, enter the archegonium of the megagametophyte; one fuses with the egg nucleus to form the zygote, the other fuses with two other nuclei of the gametophyte to form 'endosperm', which nourishes the developing embryo.

Evolution of the dominant diploid phase

It has been proposed that the basis for the emergence of the diploid phase of the life cycle (sporophyte) as the dominant phase (e.g. as in vascular plants) is that diploidy allows masking of the expression of deleterious mutations through genetic complementation.[29][30] Thus if one of the parental genomes in the diploid cells contained mutations leading to defects in one or more gene products, these deficiencies could be compensated for by the other parental genome (which nevertheless may have its own defects in other genes). As the diploid phase was becoming predominant, the masking effect likely allowed genome size, and hence information content, to increase without the constraint of having to improve accuracy of DNA replication. The opportunity to increase information content at low cost was advantageous because it permitted new adaptations to be encoded. This view has been challenged, with evidence showing that selection is no more effective in the haploid than in the diploid phases of the lifecycle of mosses and angiosperms.[31]

-

Angiosperm life cycle

-

Tip of tulip stamen showing pollen (microgametophytes)

-

Plant ovules (megagametophytes): gymnosperm ovule on left, angiosperm ovule (inside ovary) on right

-

Double fertilization

Similar processes in other organisms

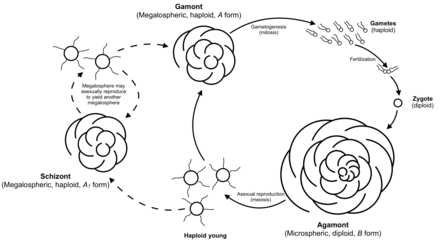

Rhizaria

Some organisms currently classified in the clade Rhizaria and thus not plants in the sense used here, exhibit alternation of generations. Most Foraminifera undergo a heteromorphic alternation of generations between haploid gamont and diploid agamont forms. The diploid form is typically much larger than the haploid form; these forms are known as the microsphere and megalosphere, respectively.

Fungi

Fungal mycelia are typically haploid. When mycelia of different mating types meet, they produce two multinucleate ball-shaped cells, which join via a "mating bridge". Nuclei move from one mycelium into the other, forming a heterokaryon (meaning "different nuclei"). This process is called plasmogamy. Actual fusion to form diploid nuclei is called karyogamy, and may not occur until sporangia are formed. Karogamy produces a diploid zygote, which is a short-lived sporophyte that soon undergoes meiosis to form haploid spores. When the spores germinate, they develop into new mycelia.

Slime moulds

The life cycle of slime moulds is very similar to that of fungi. Haploid spores germinate to form swarm cells or myxamoebae. These fuse in a process referred to as plasmogamy and karyogamy to form a diploid zygote. The zygote develops into a plasmodium, and the mature plasmodium produces, depending on the species, one to many fruiting bodies containing haploid spores.

Animals

Alternation between a multicellular diploid and a multicellular haploid generation is never encountered in animals.[32] In some animals, there is an alternation between parthenogenic and sexually reproductive phases (heterogamy), for instance in salps and doliolids (class Thaliacea). Both phases are diploid. This has sometimes been called "alternation of generations",[33] but is quite different. In some other animals, such as hymenopterans, males are haploid and females diploid, but this is always the case rather than there being an alternation between distinct generations.

See also

- Evolutionary history of plants#life cycles – History of plants: Evolutionary origin of the alternation of phases

- Ploidy – Number of sets of chromosomes in a cell

- Apomixis – Replacement of the normal sexual reproduction by asexual reproduction, without fertilization

Notes and references

- ^ "alternation of generations | Definition & Examples". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ Thomas, R.J.; Stanton, D.S.; Longendorfer, D.H. & Farr, M.E. (1978), "Physiological evaluation of the nutritional autonomy of a hornwort sporophyte", Botanical Gazette, 139 (3): 306–311, doi:10.1086/337006, S2CID 84413961

- ^ Glime, J.M. (2007), Bryophyte Ecology: Vol. 1 Physiological Ecology (PDF), Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists, archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-26, retrieved 2013-03-04

- ^ a b Kerp, H.; Trewin, N.H. & Hass, H. (2003), "New gametophytes from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert", Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 94 (4): 411–428, doi:10.1017/S026359330000078X, S2CID 128629425

- ^ Kluge, Arnold G.; Strauss, Richard E. (1985). "Ontogeny and Systematics". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 16: 247–268. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.001335. ISSN 0066-4162. JSTOR 2097049. Archived from the original on 2022-01-27. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ Taylor, Kerp & Hass 2005

- ^ ""Plant Science 4 U". Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ a b Bateman & Dimichele 1994, p. 403

- ^ a b Stewart & Rothwell 1993

- ^ a b c d e Haig, David (2008), "Homologous versus antithetic alternation of generations and the origin of sporophytes" (PDF), The Botanical Review, 74 (3): 395–418, doi:10.1007/s12229-008-9012-x, S2CID 207403936, archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-19, retrieved 2014-08-17

- ^ Svedelius, Nils (1927), "Alternation of Generations in Relation to Reduction Division", Botanical Gazette, 83 (4): 362–384, doi:10.1086/333745, JSTOR 2470766, S2CID 84406292

- ^ Hofmeister, W. (1851), Vergleichende Untersuchungen der Keimung, Entfaltung und Fruchtbildildiung höherer Kryptogamen (Moose, Farne, Equisetaceen, Rhizocarpeen und Lycopodiaceen) und der Samenbildung der Coniferen (in German), Leipzig: F. Hofmeister, retrieved 2014-08-17. Translated as Currey, Frederick (1862), On the germination, development, and fructification of the higher Cryptogamia, and on the fructification of the Coniferæ, London: Robert Hardwicke, archived from the original on 2014-08-19, retrieved 2014-08-17

- ^ Feldmann, J. & Feldmann, G. (1942), "Recherches sur les Bonnemaisoniacées et leur alternance de generations" (PDF), Ann. Sci. Natl. Bot., Series 11 (in French), 3: 75–175, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-19, retrieved 2013-10-07, p. 157

- ^ a b Feldmann, J. (1972), "Les problèmes actuels de l'alternance de génerations chez les Algues", Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France (in French), 119: 7–38, doi:10.1080/00378941.1972.10839073

- ^ Schopfer, P.; Mohr, H. (1995). "Physiology of Development". Plant physiology. Berlin: Springer. pp. 288–291. ISBN 978-3-540-58016-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foster & Gifford 1974,[page needed] Sporne 1974a[page needed] and Sporne 1974b. [page needed]

- ^ Guiry & Guiry 2008

- ^ Bateman & Dimichele 1994, p. 347

- ^ a b Shyam 1980

- ^ Watson 1981, p. 2

- ^ Kirby 2001

- ^ Watson 1981, p. 33

- ^ Bell & Hemsley 2000, p. 104

- ^ Watson 1981, pp. 425–6

- ^ Watson 1981, pp. 287–8

- ^ Sporne 1974a, pp. 17–21.

- ^ a b Bateman & Dimichele 1994, pp. 350–1

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 688–689.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Byers, G.S. & Michod, R.E. (1981), "Evolution of sexual reproduction: Importance of DNA repair, complementation, and variation", The American Naturalist, 117 (4): 537–549, doi:10.1086/283734, S2CID 84568130

- ^ Michod, R.E. & Gayley, T.W. (1992), "Masking of mutations and the evolution of sex", The American Naturalist, 139 (4): 706–734, doi:10.1086/285354, S2CID 85407883

- ^ Szövényi, Péter; Ricca, Mariana; Hock, Zsófia; Shaw, Jonathan A.; Shimizu, Kentaro K.; Wagner, Andreas (2013), "Selection is no more efficient in haploid than in diploid life stages of an angiosperm and a moss", Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30 (8): 1929–39, doi:10.1093/molbev/mst095, PMID 23686659

- ^ Barnes et al. 2001, p. 321

- ^ Scott 1996, p. 35

Bibliography

- Barnes, R.S.K.; Calow, P.; Olive, P.J.W.; Golding, D.W. & Spicer, J.I. (2001), The Invertebrates: a synthesis, Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1

- Bateman, R.M. & Dimichele, W.A. (1994), "Heterospory – the most iterative key innovation in the evolutionary history of the plant kingdom" (PDF), Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 69 (3): 345–417, doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1994.tb01276.x, S2CID 29709953, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-15, retrieved 2010-12-30

- Bell, P.R. & Hemsley, A.R. (2000), Green Plants: their Origin and Diversity (2nd ed.), Cambridge, etc.: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-64109-8

- Foster, A.S. & Gifford, E.M. (1974), Comparative Morphology of Vascular Plants (2nd ed.), San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-0712-7

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. (2008), "Cladophora", AlgaeBase, World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway, retrieved 2011-07-21

- Kirby, A. (2001), Ulva, the sea lettuce, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, archived from the original on 2011-05-16, retrieved 2011-01-01

- Scott, Thomas (1996), Concise Encyclopedia Biology, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-010661-9

- Shyam, R. (1980), "On the life-cycle, cytology and taxonomy of Cladophora callicoma from India", American Journal of Botany, 67 (5): 619–24, doi:10.2307/2442655, JSTOR 2442655

- Sporne, K.R. (1974a), The Morphology of Angiosperms, London: Hutchinson, ISBN 978-0-09-120611-6

- Sporne, K.R. (1974b), The Morphology of Gymnosperms (2nd ed.), London: Hutchinson, ISBN 978-0-09-077152-3

- Stewart, W.N. & Rothwell, G.W. (1993), Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (2nd ed.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-38294-6

- Watson, E.V. (1981), British Mosses and Liverworts (3rd ed.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28536-0

- Taylor, T.N.; Kerp, H. & Hass, H. (2005), "Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102 (16): 5892–5897, Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.5892T, doi:10.1073/pnas.0501985102, PMC 556298, PMID 15809414