| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

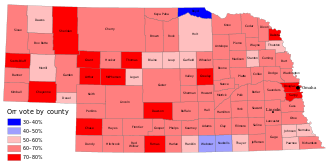

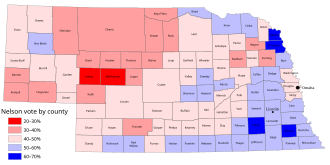

County results Nelson: 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% Orr: 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Nebraska |

|---|

|

|

|

In the 1990 Nebraska gubernatorial election, Democratic challenger Ben Nelson narrowly defeated first-term Republican incumbent Kay Orr for the governorship of the state of Nebraska.

Orr's popularity had suffered due to changes in the state's income-tax structure enacted in 1987, which were seen as a violation of her pledge not to increase taxes. The impending construction of a low-level radioactive-waste repository in north central Nebraska also occasioned discontent with her administration. In the Republican primary, she easily defeated "perennial candidate" Mort Sullivan,[1] but her winning margin was significantly smaller than expected.

Seven Democrats, four of them regarded as serious contenders, vied for their party's gubernatorial nomination. School funding, abortion, and the question of whether to establish a state lottery were among the issues that figured in the campaign. The primary election was so close that it took 48 days to declare Nelson the winner, by a margin of 41 votes.

The contest between Orr and Nelson was generally seen as an unusually negative one. Orr accused Nelson of questionable business dealings; Nelson accused Orr of violating the public trust. Each accused the other of negative campaigning. Salient issues included the 1987 tax changes; the radioactive-waste site; and a bill shifting a large portion of school funding from local property taxes to the state general fund, which included increases in the sales and income taxes, and which had passed over Orr's veto.

When the election was held, Nelson defeated Orr by a margin of 4,030 votes, with 49.91% of the vote to her 49.23%. It was suggested that a winter storm on the day of the election might have contributed to Orr's defeat, by reducing turnout among elderly and rural voters.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:1 4743341 6011 2256 484

-

Campaigns and Elections (GOVID-01: AP Government Corona Class)

-

Paul Vandervoort and Gilded Age Nebraska

-

Missouri Government and Politics: Lecture 4 - General Assembly

-

Dartmouth - Change? The 2008 Elections: Outcomes, Consequences, and Next

-

Pardons: The Power Nobody Wants | The New School

Transcription

Background

In 1986, Republican Kay Orr, who had been Nebraska's state treasurer for five years, defeated Democrat Helen Boosalis for the governorship.[2] During the campaign, Orr pledged not to increase taxes.[3]

In 1987, at Orr's urging, the state legislature passed LB773, which changed Nebraska's method of calculating its personal income tax. Up to that time, the state's income tax had been a percentage of the taxpayer's federal liability. Under the new system, Nebraska would base its tax on federal adjusted gross income, with the state establishing its own system of exemptions and deductions. Proponents argued that such a measure was necessary to produce stability and give Nebraska greater control over its state revenues; opponents objected to the fact that the measure would increase taxes on lower- and middle-income taxpayers, while decreasing them for upper-income Nebraskans. The plan as proposed by Orr would have been revenue-neutral, neither increasing nor decreasing state revenue.[4] The final version, however, as passed by the legislature and signed by Orr, increased receipts by an estimated $11–14 million.[5]

The increase in revenues was seen as a breach of Orr's pledge concerning taxes, and her popularity fell as the new system went into effect. In December 1987, a poll indicated that 60% of Nebraskans approved of her performance and 25% disapproved; by March 1988, her approval rating had dropped to 48%, while those disapproving had increased to 38%. In December 1989, the numbers stood at 47% approval and 46% disapproval.[3]

Orr's popularity was further damaged by the proposed siting of a low-level nuclear waste disposal facility in the state.[6] In 1983, during the tenure of governor Bob Kerrey, Nebraska had joined Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to form the Central Interstate Low-Level Radioactive Waste Compact, under which a single disposal site would be constructed for all five states. In 1987, the members of the compact voted 4–1 to place the facility in Nebraska. At that time, Orr declared that she was not pleased with the choice, but had to acquiesce in the other states' decision. U.S. Ecology, the company chosen to construct and operate the facility, considered a variety of sites in the state. In January 1989, they announced that they had narrowed their choices to sites in Boyd, Nemaha, and Nuckolls counties; in January 1990, they declared that they had chosen the Boyd County location.[6][7][8][9]

Democratic primary

Governor

Candidates

Seven candidates ran in the Democratic primary. Four of them were regarded as serious contenders for the nomination.

- Mike Boyle, former mayor of Omaha, Nebraska's largest city. Boyle had been elected mayor in 1981 and re-elected in 1985, but in 1987 had lost a recall election brought about by a petition drive.[10]

- Bill Harris, mayor of Lincoln, Nebraska's capital and second-largest city. Harris had represented a Lincoln district in the state legislature from 1982 until his election as mayor in 1987.[11]

- Bill Hoppner, a former staffer for elected officials J. James Exon and Bob Kerrey. Hoppner had served on Exon's staff from 1973 to 1982, initially as legal counsel while Exon was governor, then as chief of staff when Exon was elected to the U.S. Senate. He had then returned to Nebraska and served as chief of staff for governor Kerrey from 1982 to 1984; in 1989, when Kerrey took a seat in the U.S. Senate, Hoppner had again served for a year as his chief of staff.[12]

- Ben Nelson, an attorney and insurance executive. Nelson was making his first bid for elective office. In 1986, he had been the state chairman of Boosalis's unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign. In 1975–76, he had served as director of the Nebraska Department of Insurance.[13][14][15]

The other three candidates in the Democratic primary were regarded as unlikely to win; when the election was held, the three combined drew less than 3% of the vote.[12][16]

- Don Eret, a farmer from Dorchester, who had served in the state legislature from 1982 to 1986.

- Robb Nimic, a philosopher and theologian from Lincoln, who had filed as a pauper.

- Robert Prokop, a forensic pathologist from Wilber, who had held a seat on the University of Nebraska Board of Regents from 1971 to 1982.

Issues

Taxes and school funding

One of the foremost issues in the Democratic primary concerned school funding. In April 1990, the legislature passed LB1059, which made major changes to the financing of public education in the state. Prior to its passage, roughly 70% of the money for primary and secondary schools came from property taxes and other local sources.[17] The expressed goal of the bill's supporters was to increase the state's contribution to school districts from 25% of operational costs to 45%; this would be funded through a 25% increase in the sales tax and a 17.5% increase in the personal income tax. Proponents maintained that the measure would lessen inequality among school districts and would avert a significant increase in property taxes; they also noted that courts in several other states had struck down locally financed educational systems such as Nebraska's. Opponents argued that the increased taxes would prove burdensome to Nebraskans, particularly the poor, and expressed doubt that the measure would prevent substantial property-tax increases.[18] The bill passed; Orr vetoed it, but was overridden.[19]

Of the four leading Democratic candidates, Boyle, Harris, and Nelson declared that they would have vetoed the bill,[20] arguing that it would not in fact lead to long-term property-tax relief.[21] Hoppner expressed enthusiastic support for the measure, "because it's at the heart of the traditional Democratic message of this state, because the people of this state care about our children".[22]

Other issues

Another issue raised in the Democratic primary was the question of whether a state lottery should be established in Nebraska; and, if established, what use should be made of the revenues generated thereby. Of the four major candidates, Harris indicated that he was generally opposed to a lottery. Boyle proposed that proceeds be used for property-tax relief; Hoppner declared that they should be used for special one-time expenses, and not for routine spending; and Nelson maintained that they should be used to augment basic spending on education.[20][23]

Harris and Hoppner both declared themselves supporters of abortion rights, and were endorsed by the pro-choice organization Nebraska Voters for Choice. Boyle expressed opposition to abortion, and received the endorsement of pro-life organizations Metro Omaha Right to Life and the Nebraska Coalition for Life. Nelson also declared himself an opponent of abortion, but said that if the legislature passed abortion-rights legislation, he would neither veto nor sign it, allowing it to become law without his signature.[24][25]

All four of the major Democratic candidates asserted that illegal drug use was one of the critical issues in the campaign; Harris stated that it was the number-one issue facing Nebraska and the nation. All four were opposed to drug abuse and crime.[21][26]

Nelson and junk bonds

In the final two weeks before the primary election, Nelson came under attack from Harris and Hoppner for his involvement with life-insurance holding company First Executive, for which he had acted as a consultant and director; he and his law firm had collected over $1.8 million in fees from the company. First Executive had large holdings in junk bonds, which had recently received a great deal of unfavorable attention related to investment banking firm Drexel Burnham Lambert's February 1990 declaration of bankruptcy, and to Drexel employee Michael Milken's April 1990 conviction for securities fraud. Nelson maintained that he had played no part in the junk-bond investment decisions of First Executive, having only joined the company's board in 1988.[13][27][28][29]

Strategy and spending

Nelson led the field in campaign contributions and spending; by the end of April, his campaign had spent $593,000. In the same time period, Hoppner had spent $326,000; Harris, $156,000; and Boyle, less than $60,000.[30] Nelson was criticized for accepting large contributions from insurance companies in Chicago and California;[24] he had also loaned his campaign over $360,000, a sum far greater than that borrowed by any of the other candidates.[31]

The number of viable candidates complicated the devising of campaign strategies. Under more ordinary circumstances, a candidate could win a statewide Nebraska Democratic primary by winning heavily in five eastern counties, containing just over half of the state's registered Democrats: Douglas and Sarpy counties, which include the Omaha metro area; Lancaster County, including Lincoln; and Dodge and Saunders counties. In this election, however, every Democratic vote had to be sought, which made it necessary to direct campaign efforts to the Third Congressional District, consisting of the western three-quarters of the state. Although the Third District was one of the most Republican congressional districts in the nation, its small population of Democrats might prove crucial in the final vote count.[32]

The four candidates had four different strategies. Boyle's was based on securing a strong lead in Omaha, from voters who had supported him as mayor, and on doing well among conservative Democrats in the Third District, attracted by his pro-life stance and endorsements. Harris expected to win heavily in Lancaster County, and to draw votes from more socially-liberal Democrats throughout the state because of his pro-choice position; he had secured the endorsement of Democratic former governor Frank Morrison, who campaigned with him throughout Nebraska. Hoppner depended on the support of activist and party-line Democrats, drawn by his pro-choice stance, his support for LB1059, and his association with Exon and Kerrey;[32] four days before the election, he received a formal endorsement from Kerrey, and began broadcasting a television commercial in which the senator declared his support for Hoppner.[33]

Nelson's strategy was the most focused on the Third District: his campaign's goal was to minimize his losing margin in Omaha and Lincoln, while winning heavily in rural Nebraska.[27] His advantage in funding proved important in this. While Hoppner relied on television advertising on stations in Omaha, Lincoln, Grand Island, Hastings, Kearney, and North Platte, Nelson bought advertising in all of those markets and also on Sioux City, Iowa television, which reached northeastern Nebraska, and on radio station KRVN in Lexington, Nebraska, with a large listenership in rural central and western Nebraska. To reach more voters who were outside of the areas covered by the eastern and central television stations, he staged a direct-mail campaign, sending up to three letters to registered Democrats in rural areas near the state's northern, southern, and western borders.[34]

Newspaper endorsements

There was no consensus among the daily newspapers of the state regarding the Democratic candidates. The state's largest newspaper, the Omaha World-Herald, which then circulated throughout Nebraska, endorsed Harris, noting in particular his opposition to gambling.[35] The Grand Island Independent also endorsed Harris alone. The Lincoln Journal found Harris, Hoppner, and Nelson all worthy candidates. The Lincoln Star and the Fremont Tribune endorsed Hoppner; the Kearney Hub, Boyle; and the North Platte Telegraph, both Boyle and Hoppner.[36]

Results

Polls conducted days before the May 15 election showed no clear winner in the Democratic primary: any of the four major candidates might have won. Further polling showed no clear outcome in hypothetical matchups between any of the four and Orr.[37][38]

Of the 363,778 registered Democrats in the state, 172,812, or 47.5%, voted in the primary; 166,744 of them cast ballots in the gubernatorial race.[39] As the ballots were counted, Harris quickly fell behind the other three major candidates; in Lancaster County, on which he had counted heavily, he ran in third place, behind Hoppner and Nelson. Harris attributed his poor showing to the fact that he and Hoppner had split the pro-choice vote, and to Kerrey's late endorsement of Hoppner.[40] Boyle led Hoppner in Douglas County by 11,000 votes, and until about midnight he held the lead; however, his support outside of the Omaha area was not strong, and he was forced to admit defeat soon thereafter.[27]

On the morning of May 16, Hoppner and Nelson were virtually tied, with only a few hundred votes between them, absentee ballots still to be counted, and a recount almost certain to be held, as required by state law for cases when two leading candidates were within one percentage point of one another.[27] The recount in fact proved necessary; and so close was the contest that only on July 3, some 48 days after the election, was Nelson certified the winner,[41] by a margin of 41 votes: 44,556 to Hoppner's 44,515.[16]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Ben Nelson | 44,556 | 26.72 | |

| Democratic | Bill Hoppner | 44,515 | 26.70 | |

| Democratic | Mike Boyle | 41,226 | 24.72 | |

| Democratic | Bill Harris | 31,516 | 18.90 | |

| Democratic | Robert Prokop | 2,762 | 1.66 | |

| Democratic | Don Eret | 1,295 | 0.78 | |

| Democratic | Robb Nimic | 724 | 0.43 | |

| Democratic | Write-ins | 150 | 0.09 | |

| Total votes | 166,744 | 100.00 | ||

Lieutenant governor

Under the state constitution as it existed in 1990, parties chose their nominees for governor and lieutenant governor in separate votes in the primary; the two nominees from each party then ran as a ticket in the general election. In the Democratic lieutenant-gubernatorial race, five candidates ran; the winner was Maxine Moul.[12]

Candidates

- Keith B. Edquist, businessman, owner of Husker-Hawkeye Distributing Co., former member of the Bellevue, Nebraska, City Council, and member of the Omaha Public Power District board[42]

- Ken L. Michaelis, disbarred attorney from West Point, Nebraska, who was an unsuccessful candidate for lieutenant governor in 1986 and US Senator in 1988[42]

- Maxine Moul, co-owner with her husband of Maverick Media, which published five newspapers and several shoppers from Syracuse, Nebraska[42][43]

- Gary L. Rogge, farmer from Auburn, Nebraska, and past vice president of Concerned Citizens of Nemaha County, seeking the office to address issues with radioactive waste[42]

- Steve Wiitala, former member of the Nebraska Legislature in District 31 from 1981 to 1983, former Douglas County election commissioner, and former campaign manager for Bob Kerrey's 1982 gubernatorial campaign from Omaha, Nebraska.[42][44][45]

Results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Moul | 40,043 | 29.85 | |

| Democratic | Steve Wiitala | 35,953 | 26.80 | |

| Democratic | Ken L. Michaelis | 22,284 | 16.61 | |

| Democratic | Gary L. Rogge | 17,980 | 13.40 | |

| Democratic | Keith B. Edquist | 17,645 | 13.15 | |

| Democratic | Write-ins | 235 | 0.18 | |

| Total votes | 134,140 | 100.00 | ||

Republican primary

Governor

Orr faced only nominal opposition in the Republican primary, which drew little media attention. Only two names appeared on the Republican ballot.

Candidates

- Kay Orr, one-term incumbent governor.

- Mort Sullivan, described by the Omaha World-Herald as a "perennial candidate".[1] Sullivan owned an Omaha company that operated automatic telephone-dialing machines;[47] in 1989, he had run in the Omaha mayoral election, placing sixth.[27]

Results

In the Republican primary, Orr had been expected to win easily, and did. However, Sullivan received about 31% of the vote, unpleasantly surprising Orr, who had expected him to win from 15% to 25%. Orr attributed this to Republican dissatisfaction with some of her decisions as governor, including the tax changes of 1987.[48] Sullivan's unexpectedly high percentage was also attributed in part to Orr's failure to oppose the proposed radioactive-waste repository: he defeated her in Boyd County, chosen for the site; in Nuckolls County, which had been one of the three finalists considered by U.S. Ecology; and in Webster County, which borders Nuckolls County and which had been among the locations initially considered for the disposal site.[47]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Kay Orr (incumbent) | 130,045 | 68.11 | |

| Republican | Mort Sullivan | 59,048 | 30.92 | |

| Republican | Write-ins | 1,848 | 0.97 | |

| Total votes | 190,941 | 100.00 | ||

Lieutenant governor

Orr's incumbent lieutenant governor, Bill Nichol, did not run for re-election.[50] Jack Maddux, backed by much of the state's Republican establishment and endorsed by Nichol,[51] won with 67.2% of the vote to Brettman's 32.5%.[12]

Candidates

- Roy Brettmann, businessman and owner of Big Sur and Tops Real Estate from Omaha, Nebraska[42]

- Jack Maddux, cattleman, former mayor of Wauneta, Nebraska, and member of the Ameritas board, the Nebraska Wesleyan University board of trustees, and the University of Nebraska Foundation board[42]

Results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Jack Maddux | 103,900 | 67.20 | |

| Republican | Roy Brettmann | 50,180 | 32.46 | |

| Republican | Write-ins | 533 | 0.34 | |

| Total votes | 154,613 | 100.00 | ||

General election

The campaign leading up to the general election was regarded as an unusually negative one;[7] an Omaha World-Herald editorial described it as a "long, cruel, issue-less campaign".[52] Nelson's campaign manager accused Orr's campaign of "negative cheap shots";[53] Orr's campaign manager accused Nelson of "stridently negative attacks".[54] Nelson's campaign declared that Orr had "no credibility because she has violated the public trust";[55] Orr's accused Nelson of "vicious attacks".[56] In an October debate, Nelson accused Orr of "constant attacks on my character, constant attacks on my family relations", while Orr accused Nelson of "the worst type of negative campaigning this state has ever seen".[57]

Issues

Junk bonds redux

In July, Nelson announced that he would not seek re-election to First Executive's board when his term expired at the end of the month, stating that his campaign would not leave him time to fulfill his duties as a director, and that his resignation had nothing to do with the company's history of junk-bond dealings.[58] In September, Orr's campaign ran a commercial stating that Nelson, as a consultant and director of the company, must have been involved in its decisions to invest in junk bonds.[56] In an October radio interview, she said "My opponent owns a company with Mike Milken"; she subsequently issued a partial retraction, calling Nelson "a business associate with Mike Milken".[59] Nelson declared that Orr had "resorted to negative campaigning in order to save her job",[56] and denied any relationship with Milken.[59]

Orr called for Nelson to make his income-tax return public, providing her own to the Omaha World-Herald in a sealed envelope, to be opened if Nelson's were also made available. Nelson declined to do so, for reasons of "privacy and security",[60] declaring that he had provided all the records required by the law, and accusing Orr of demanding them as a diversionary tactic.[61]

Taxes and spending

Nelson pressed the issue of taxes, maintaining that the 1987 restructuring had increased taxes on lower- and middle-class taxpayers, while decreasing them for the wealthy.[54] Orr responded by citing a Deloitte and Touche study finding that taxes on most low and middle incomes were lower in 1989 than they had been in 1986; state senator Don Wesely, a Nelson consultant, denounced the study as "political propaganda to mislead the public".[62]

Nelson accused Orr of profligate spending, noting that the state budget had increased by 40% during the first three years of her governorship.[63] Orr's campaign responded that the steep increase was partly due to essential spending deferred during the nationwide recession of the early 1980s and the farm recession of the mid-80s; partly due to the state takeover of the welfare system, which had previously received some of its funding from the counties; and partly due to a 65% increase in Medicaid costs.[64]

A petition drive was launched to repeal school-finance bill LB1059. Orr ran radio commercials in support of the repeal, calling the bill "a record tax increase" and noting that she had vetoed it.[65] Nelson declined to sign the petition, stating that the bill, though flawed, should be corrected by the legislature rather than repealed altogether. Orr's campaign condemned this, declaring that Nelson was "trying to get votes from people on both sides by riding the fence".[53]

Boyd County

In July 1990, Kerrey withdrew his support from the proposed radioactive-waste repository in Boyd County, asserting that the facility might no longer be needed and might not be economically feasible. Nelson joined Kerrey in calling for a moratorium on further work. Orr declared that she would be willing to suspend the process, if Kerrey could guarantee that Nebraska taxpayers and power consumers would not suffer, but expressed concern that such a move might be a violation of federal law; an Orr staffer cited a study indicating that costs of withdrawing from the waste-disposal compact would be at least $150 million, and might be as high as $425 million.[66][67][68]

Nelson declared that "[i]f I am elected governor, it is not likely that there will be a nuclear dump in Boyd County or in Nebraska".[69] He called for a debate in Boyd County, and accused Orr of a "lack of leadership" on the matter;[70] in mid-October, he held a rally in the county at which he chided his opponent for her unwillingness to campaign there, and declared that more forceful opposition by Orr would have prevented the decision to locate the site in Nebraska.[71] Following the rally, the Boyd County Republican Committee announced its unanimous endorsement of Nelson over Orr.[72]

Other issues

Orr accused Nelson of "lacking leadership" on abortion, declaring that she would veto any bill that relaxed restrictions on the procedure.[73] The Nebraska Coalition for Life endorsed Orr, with the comment that "[Nelson's] position is no position at all".[74]

The candidates differed on a measure on the ballot, promoted by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, that would legalize video slot machines. Nelson supported the measure, and stated that if elected, he would propose an amendment to the Nebraska constitution that would authorize a statewide lottery. Orr opposed the video-slot measure, and any attempt to establish a state lottery.[75]

Orr claimed credit for the state's 2% unemployment rate.[54] She emphasized her party affiliation, declaring "This is a Republican state."[76] She asserted that Nebraskans knew her and her record as a public official, while Nelson was an unknown quantity.[77]

Campaigns and spending

Orr spent twice as much as Nelson, in what the Omaha World-Herald described as "the most expensive governor's race in state history".[78] President George H. W. Bush visited Omaha to raise funds for her and for two Republican Congressional candidates.[79] She secured an endorsement from University of Nebraska athletic director Bob Devaney, revered in Nebraska for his success as the coach of the university football team.[7]

Twelve of Nebraska's daily newspapers, including the World-Herald and the Lincoln Star, endorsed Orr. Nelson garnered two endorsements, from the McCook Daily Gazette and the Fremont Tribune (the latter of which endorsed Orr as well). The Lincoln Journal declined to endorse either candidate, accusing both of negative and mean-spirited campaigning.[80]

Two weeks before the election, the Orr campaign discovered that Dresner Sykes, their media-consulting firm, had charged the campaign for television advertising time that was never purchased. A World-Herald analysis after the election determined that Creative Media, the firm's advertising placement agency, had charged the campaign $34,860 for October advertising on Omaha station KMTV, while actually purchasing $6,115 worth of time, or 17.5% of that ordered. A similar pattern obtained on other stations in Omaha, Lincoln, North Platte, and Sioux City, with Creative Media actually purchasing between 12% and 88% of the time ordered by the campaign. Although the campaign had ordered advertisements placed on Omaha television stations every day during the period October 5–22, nothing ran on at least four days of the period. Dresner Sykes reimbursed the Orr campaign with a $50,000 check and with the cancellation of unpaid bills; but Orr could not recover the lost advertising time in the past, and found that the most desirable advertising times for the rest of the campaign's duration were already taken.[81][82]

General election results

On November 6, the day of the election, a winter storm struck central Nebraska, depositing up to 12 inches (300 mm) of snow and ice. Secretary of State Allen Beerman estimated that up to 50,000 voters might have been kept from the polls by the weather. The storm reduced turnout in the Third District and among elderly voters, who historically tended to support Republicans. Before ballot-counting was complete, Beerman suggested that the weather might have cost Orr the election.[82][83]

Unofficial results on election night gave Nelson a lead of 4,658 votes out of nearly 570,000. As absentee ballots were counted, it became clear that they would not change the outcome; Orr conceded to Nelson on November 9.[84]

The official results gave Nelson 292,771 votes (49.91%) to Orr's 288,741 (49.23%). Sullivan, running as a write-in, garnered 1887 votes (0.32%); other write-ins received 3143 votes (0.54%).[85] Nelson won 19 counties that the Republicans had won in the 1986 gubernatorial election, many of them in areas that had been suggested as locations for the radioactive-waste disposal site.[13]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Ben Nelson | 292,771 | 49.91 | ||

| Republican | Kay Orr (incumbent) | 288,741 | 49.23 | ||

| Write-in | Mort Sullivan | 1,887 | 0.32 | ||

| Write-in | Others | 3,143 | 0.54 | ||

| Total votes | 586,542 | 100.00 | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

Other votes

Nebraska voted on four seats in the U.S. Congress: one in the Senate and three in the House of Representatives. All three incumbents running were re-elected. Exon, a Democrat, won re-election to the Senate, securing 59% of the vote to defeat Republican Hal Daub. Republican Doug Bereuter was re-elected to the First District House seat, with 65% of the vote to Democrat Larry Hall's 35%. In the Second District, one-term incumbent Peter Hoagland, a Democrat, received 58% of the vote to Republican Ally Milder's 42%. In a race for an open House seat in the Third District, Republican Bill Barrett defeated Democrat Sandra K. Scofield, taking 51.1% of the vote to her 48.8%.[87][88][89][90]

The LB1059 repeal effort, which Orr had supported and Nelson opposed, failed: 44% of the votes cast supported repeal, while 56% favored keeping the measure. A World-Herald article noted that opposition to repeal was especially high in areas where rural school districts were receiving large amounts of state aid, and that support for repeal was strongest in Douglas County.[53][65][91][92]

The ballot measure to legalize and regulate video lotteries, which Nelson had supported and Orr opposed, also failed. Votes in favor of the measure amounted to only 35% of the total, while 65% were opposed.[75][93]

Nationally, the Democratic Party made small gains in the U.S. Congress, with an increase of one seat in the Senate and eight in the House of Representatives. Incumbent governors fared poorly: the incumbent party lost in 14 of the 36 contests, including two in which independent candidates won.[94][95] Governors who had reneged on pledges not to allow tax increases suffered badly; beside Orr, Republicans Mike Hayden of Kansas and Bob Martinez of Florida were rejected by the voters.[96]

Notes

- ^ a b Stern, Gabriella. "Gov. Orr Says She Sees 'Hard Work' Ahead". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-16. p. 15.

- ^ "Archives Record: Orr, Kay".[usurped] Nebraska State Historical Society.[usurped] Retrieved 2011-12-15.

- ^ a b Robbins, William. "For Nebraska Governor, a Hard Path". https://www.nytimes.com/ New York Times. 1990-02-09. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ^ "Tax plan to provide stability—commissioner". Unicameral Update. 1987-02-13. p. 3.

- ^ "Income tax measure passed, signed". Unicameral Update. 1987-05-08. p. 6.

- ^ a b Robbins, William. "Politics Overtake Selecting Nuclear Dump Sites". New York Times. 1990-09-30. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, William E. "Nebraska Governor in Fight To Save Her Political Career". New York Times. 1990-11-03. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Kevin. "Epilogue: Nuke dump battle peaked 10 years ago this month". Lincoln Journal Star. 2011-07-04. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ U.S. General Accounting Office. "Nuclear Waste: Extensive Process to Site Low-Level Waste Disposal Facility in Nebraska". Report to U.S. Senator J. James Exon, July 1991. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ "Ousted Omaha Mayor Seeking Re-election". New York Times. 1989-03-05. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ^ Discoe, Connie Jo. "Former state senator, Lincoln mayor Bill Harris dies at 71". McCook Daily Gazette. 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ a b c d Kotok, C. David. "Tight Race to Pick Orr Opponent". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-10. p. 51.

- ^ a b c "Earl Benjamin Nelson". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ "Helen Boosalis Dies". Archived 2012-05-19 at the Wayback Machine KOLN/KGIN TV. 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ "Ben's Biography". Archived 2012-12-11 at the Wayback Machine Ben Nelson U.S. Senate website. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ a b c "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", primary election, p. 10.

- ^ "Education, Revenue panels advance public school finance measure". Unicameral Update. 1990-01-26. pp. 10-11.

- ^ "Legislature advances major bill to change school finance system". Unicameral Update. 1990-03-09. pp. 4-5.

- ^ "Lawmakers override Orr veto on school finance measure." Unicameral Update. 1990-04-13. pp. 12-13.

- ^ a b Koopman, John. "Democrats Exchange Final Debate Blows". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-03. p. 1.

- ^ a b Kotok, C. David. "4 Candidates For Governor Give Views". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-06. p. 8B.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Hoppner Says Nelson's Stands Are 'Election Losers'". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-10. p. 25.

- ^ Rosse, Sharon. "Nelson Says Rivals Wrong About Lottery Proposal". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-02. p. 32.

- ^ a b Koopman, John. "Boyle Criticizes Out-of-State Gifts". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-05. p. 37.

- ^ Thomas, Steve. "Both Sides of Abortion Issue Say They Scored Victories in Primary". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-17. p. 43.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Harris Says Critics Wrong In Charging He's Indecisive". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-02. p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e Kotok, C. David. "Nail-Biter Election Comes Down to Hoppner, Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-16. pp. 1, 15.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Nelson's Links to Firm Date to '85". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-08. p. 12.

- ^ Eichenwald, Kurt. "Milken Set to Pay a $600 Million Fine in Wall St. Fraud". New York Times. 1990-04-21. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Focus of Race For Governor Turns to Polls". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-14. p. 1.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Loans Help Finance Late Ad Blitz". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-10. p. 26.

- ^ a b Kotok, C. David. "Four Democrats See 3rd District As Key to Primary". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-13. p. 1.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Hoppner Gets Backing From Former Boss Kerrey". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-12. p. 35.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "State's Border Counties Proving Essential to Nelson's Campaign". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-22. p. 1.

- ^ "Harris Has What It Takes To Be a Good Governor". Editorial, Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-08. p. 18.

- ^ "Campaign Watch". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-12. p. 39.

- ^ "Survey: Democrats' Race For Governor Still Close". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-13. p. 1.

- ^ "Poll Indicated 4 Governor Hopefulls Tied, Many Democrats Undecided". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-13. p. 6A.

- ^ "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", primary election, pp. 1, 10.

- ^ Stern, Gabriella. "Harris: Kerrey Backing of Hoppner Hurt Bid". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-16. p. 15.

- ^ "Winner in Nebraska at Last; The Margin: 0.047 Percent". New York Times. 1990-07-04. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g Steve Thomas (April 22, 1990). "5 Democrats, 2 Republicans, Vie for Lieutenant Governor". Omaha World-Herald. p. 44. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ "Maxine Moul serves Nebraskans from the Capitol". University of Nebraska College of Journalism and Mass Communications Archive. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Previous Election Commissioners". Douglas County Election Commission. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ Nebraska Blue Book 1980–1981 Archived 2017-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, p. 259. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", primary election, p. 11.

- ^ a b Dorr, Robert. "Mort Sullivan Outpolled Gov. Orr in Three Counties". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-17. p. 43.

- ^ "Gov. Orr Plots Strategy to Unite Republican Voters for November". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-17. p. 43.

- ^ a b c "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", primary election, p. 5.

- ^ According to "Former Lt. Gov., state Sen. Bill Nichol dies", Sioux City Journal, 2006-12-01, retrieved 2016-01-22, Nichol "retired from public service after he and Orr were defeated for re-election... in 1990". This is apparently an error: Nichol's name does not appear in "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", primary election, p. 11, which lists the results of the Republican lieutenant-gubernatorial primary.

- ^ "Nichol endorses Jack Maddux". Lincoln Journal Star. May 2, 1990. p. 21. Retrieved June 22, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Nelson-Kerrey Blitz Deceptive". Omaha World-Herald editorial. 1990-11-04. p. 28A.

- ^ a b c Kotok, C. David. "GOP Critics Assail Nelson on Two Fronts". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-11. p. 27.

- ^ a b c Cordes, Henry J. "Jobs, Tax Hike Put Orr Team, Nelson at Odds". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-06-30. p. 35.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Both Camps Put Best Face on Poll". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-05.

- ^ a b c Kotok, C. David. "Orr Ad Mentions Junk Bonds; Nelson Says TV Spot Is Negative". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-08. p. 15.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Gov. Orr, Ben Nelson Land Debate Punches". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-17. p. 1.

- ^ Stern, Gabriella. "Nelson to Leave Board Tied to Junk Bond Issue". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-08. p. 1.

- ^ a b Kotok, C. David. "Gov. Orr Says 'Wrong Word' Used in Comment About Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-18. p. 1.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Nelson, Gov. Orr Squabble on Tax Returns". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-27.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Handshake and Heated Words Mark Final Orr-Nelson Debate". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-24. p. 1.

- ^ Cordes, Henry J. "Tax Study Attacked As Political". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-29. p. 33.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Nelson Criticizes Orr Spending Increase". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-28.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Orr Spending Called Answer to 'Lean Years'". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-30. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Gov. Orr Joins Effort To Repeal LB 1059". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-11. p. 27.

- ^ de Zutter, Mary. "Kerrey: Do Not Construct Radioactive Waste Facility". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-16. p. 1.

- ^ Garfield, Daniel. "Orr Aide Calls Nelson's Timing on Waste Site Political". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-18. p. 13.

- ^ Anderson, Julie. "Nelson Denies Playing Politics With Issue of Waste Facility". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-07-19. p. 17.

- ^ Nelson quoted in Entergy Arkansas, Inc. et al. v. Nebraska. U.S. District Court, Nebraska. p. 85. 2002-09-30. Retrieved 2015-02-23. Archived 2015-02-05 at Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Nelson Calls for Debate in Boyd County". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-08-04. p. 25.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Nelson Rallies Site Opponents In Boyd County". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-15. p. 9.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Boyd GOP Backs Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-16.

- ^ Stern, Gabriella. "Gov. Orr Launches Attack on Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-05-19. p. 59.

- ^ "Abortion Opponents Back 21 Candidates". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-03.

- ^ a b Kotok, C. David. "Gov. Orr, Nelson Clash On 2 of 7 Ballot Issues". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-09-30. p. 1.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Candidates Feud Over Finances". Omaha world-Herald. 1990-11-02. p. 21.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Gov. Orr Calls on Nelson to Release Returns." Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-01. p. 23.

- ^ Kotok, C. David. "Governor's Race a Squeaker". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-07. p. 1.

- ^ Gauger, Jeff. "Orr Camp Paid $19,200 for Bush Visit". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-10-31.

- ^ "12 Daily Papers Endorse Gov. Orr; 2 Tab Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-02.

- ^ Kotok, C. David, and Gabriella Stern. "Orr, Tauke Audits Found TV Time Lost". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-11. p. 1.

- ^ a b Walton, Don. "Opening the history books on Kay Orr's legacy". Lincoln Journal Star. 2013-02-10. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ Dorr, Robert. "Some Areas Saw Snow, Turnout Fall". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-09. p. 1.

- ^ Brennan, Joe. "Gov. Orr Concedes to Nelson". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-10. p. 1.

- ^ "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", general election, p. 5.

- ^ County data from "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", general election, p. 5. In Stanton and Hall counties, Nelson won a small plurality of the vote; however, because of write-in votes, he failed to secure a majority. Thus those counties are colored in shades of red on the map, although Nelson can be said to have won them.

- ^ "Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 6, 1990". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. p. 22. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Bereuter, Douglas Kent, (1939–)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Hoagland, Peter J., (1941–2007)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived 2010-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ Schneider, Keith. "Among Farmers, Anger Greets Prospect of Cuts". New York Times. 1990-10-04. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", general election, p. 44.

- ^ Flanery, James Allen. "Senator: Coalition Saved LB1059". Omaha World-Herald. 1990-11-08. p. 21.

- ^ "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers", general election, p. 42.

- ^ Toner, Robin. "Voters Oust Governing Party in 14 States; Congress is Shaken But Few Are Unseated". New York Times. 1990-11-08. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ^ Apple, R. W., Jr. "The 1990 Elections: Signals - The Message; The Big Vote Is for 'No'". New York Times 1990-11-08. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ^ Rasky, Susan F. "Four Issues and How They Played at the Polls Before Uncertain Voters; Taxes: Voters Send Mixed Message". New York Times. 1990-11-08. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

References

- "Official Report of the Board of State Canvassers of the State of Nebraska: Primary Election May 15, 1990, General Election November 6, 1990". Retrieved 2016-01-19.