In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen.[1] Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European colonization, particularly when European explorers and colonists brought diseases to lands they conquered in the Americas, Australia and Pacific Islands.[2]

When a population has been isolated from a particular pathogen without any contact, individuals in that population have not built up any immunity to that organism and also have not received immunity passed from mother to child.[3] The epidemiologist Francis Black has suggested that some isolated populations may not have mixed enough to become as genetically heterogeneous as their colonizers, which would also have affected their natural immunity, due to the potential benefits to immune system function due to genetic diversity.[3] That can happen also when such a considerable amount of time has passed between disease outbreaks that no one in a particular community has ever experienced the disease to gain immunity.[4] Consequently, when a previously unknown disease is introduced to such a population, there is an increase in the morbidity and mortality rates. Historically, that increase has been often devastating and always noticeable.[2]

Diseases introduced to the Americas by Europeans and Africans include smallpox, yellow fever, measles and malaria as well as new strains of typhus and influenza.[5][6]

Virgin soil epidemics also occurred in other regions. For example, the Roman Empire spread smallpox to new populations in Europe and the Middle East in the 2nd century AD, and the Mongol Empire brought the bubonic plague to Europe and the Middle East in the 14th century.[6]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:6 8595313445 25217 588

-

Virgin Soil and European Immigrants

-

''Virgin Soil'' Epidemics and Demographic Collapse in the Americas

-

'Smallpox epidemics and Southeast Indian Survival' with Dr Jon Chandler

-

Gideon Mailer - Nutrition, Immunity, and the Warning from Early America

-

Germs, Genocide and America's Indigenous Peoples

Transcription

As everybody knows, when Europeans arrived in the New World in the late 1400s, they find the land already occupied. What not everybody knows, perhaps, is how heavily occupied it was. Many historians now think that somewhere between 50 million and 100 million Native Americans lived in North and South America. And many of them lived in large, complex societies, states, if you will, that were larger than any European state. So the New World was not truly virgin soil for the European settlers. But the immune systems of the people who lived there were, in fact, virgin soil for the bacteria and the viruses that Europeans unwittingly brought with them. And they began to die in droves. In fact, some people think 90% of them died within the first century after contact with Columbus. As European settlers moved in, they still faced considerable resistance, but they had the opportunity to grab far more land and riches than many of them would have ever been able to obtain in the Old World. The result for them is a shift in expectations, a shift away from narrower constraints, a shift towards a more open world, in which, perhaps, we see the beginnings of an expectation, a set of expectations that would play a role in moving people to push beyond the old constraints of the Malthusian economy, the old constraints of the agricultural world that had limited people for over 10,000 years. So the numbers I was talking about, 50 million, 60 million, 80 million dead, are so big, and the geographical scope, an entire hemisphere, North and South America, is so extensive that at times it can seem like all of the death and destruction blurs together. So let me try to get a little bit more specific and a little bit more localized. Let's talk about the island of Hispaniola, one of the first places Columbus comes to in 1492. At that time there are approximately 1 million Taino Indians living on the island of Hispaniola. By the time a century has passed, a century a Spanish domination, of enslavement and violence, and above all death from disease, there are only 5,000 Tainos remaining. Virtually the entire population had been wiped out, and soon all that remains of their culture and their history is what had been written down by the conquerors. The devastation is so complete that when escaped slaves are wandering in the mountains they find artifacts left behind by the Tainos, and they wonder who those people were. But when the slaves rise up, in what becomes the world's biggest slave rebellion, 1791, a rebellion that ultimately becomes a war for independence, in which they create a new nation, and they come together to decide what to call that nation, they decide to memorialize the people who came before them. And again, they have to go to the Spanish books to find the name that the conquerors had written down, the name that the people who came before had actually given the island. And that name is Haiti. And that's what they call their new country. Historians call the movement of people, products, ideas, and organisms across the Atlantic in both directions in the years after 1492, the Columbian Exchange. And it's an apt term because things were moving in both directions. Obviously, disease organisms move west across the Atlantic. And what Native Americans receive, above all, is death and the destruction of societies. Europe, on the other hand, benefits directly from products that move across the Atlantic to the East. Spain, in particular, gets tons, literally tons, of gold and silver in the first century after 1492. And they're able to use that gold and silver to build an empire, an empire that doesn't last, but is very powerful in Europe and around the world while it does. Other countries, of course, benefit as well economically, and we'll talk more about them as we go along. But we should mention that if organisms are moving west across the Atlantic, they're also moving east. Organisms, like the plant that we know as corn or maize, the potato, the sweet potato, cassava, tomatoes, and many other products, which are today essential parts of European, African, and Asian cuisines, and help through their benefits and the way that they can produce many calories from relatively small inputs of labor and land, through those abilities they're able to increase the population of the Old World tremendously between 1500 and today. Now, for settlers who move west, there are many benefits as well. For European settlers, it is. For enslaved Africans, not so many. But for free Europeans, what they find is not only that they can have much more wealth, not only that they can have much more status than they had in the old world, they even find that their bodies are different. They are, if you will, beneficiaries of the catastrophe that hits Native Americans and enslaved Africans so hard. By the 1700s, Europeans or people of European descent, I should say, born in the New World colonies are visibly healthier, stronger, and taller on average than their cousins who are born in Europe. There's a famous anecdote of a dinner in Paris, where Thomas Jefferson was present. And there was also a French philosoph there, who had the theory that things in the New World were degenerate compared to those in the Old World. The animals were smaller, he claimed. The bears were smaller. Jaguars were smaller than tigers, and so on and so forth. Jefferson simply said, let's all stand up. All the Americans are on this side of the table. The French are on this side of the table. And he said, once they did, who is smaller now? That's an entertaining anecdote, but if we had gone back to Monticello and measured the height of Jefferson's slaves, we would find that on average they would have been at least an inch shorter then people of the corresponding gender and age who were at Jefferson's side of the table in Paris. The fact is for the first 300 years of the Columbian Exchange, the movement from the old world to the new, of the people who come from the old world to the new, 8 million of the 11 million come in the bottom of slave ships, chained together, many of them not even surviving the voyage. Enslaved Africans, in fact, would be a majority of all immigrants from the old world to the new until deep into the 19th century. And of course, at the same time, it was the deaths of well over 50 million people from epidemic disease that had cleared the way for the farms and the plantations and for whites, at least, the opportunities that would so characterize the New World experience for many centuries after. So it's fair to say that the European colonies and the colonists who come to them are able to get a new sense, a new set of dreams and a new set of ideas in large part because they are, as one historian put it and I just put it a few minutes ago, beneficiaries of catastrophe.

History of the term

The term was coined by Alfred Crosby[1] as an epidemic "in which the populations at risk have had no previous contact with the diseases that strike them and are therefore immunologically almost defenseless." His concept is related to that developed by William McNeill, who connected the development of agriculture and more sedentary life with the emergence of new diseases as microbes moved from domestic animals to humans.[7]

The concept would later be adopted wholesale by Jared Diamond as a central theme in his popular book Guns, Germs and Steel as an explanation for successful European expansion.[8]

Historical instances

Native American epidemics

Due to limited interaction between communities and more limited instances of zoonosis, the spread of infectious diseases was generally hampered in Native American communities. This contrasted with Eurasia, where a large number domesticated animals in close contact with large human populations would lead to more frequent zoonotic diseases, which would then in turn spread between human populations more easily due to trade and warfare. Native Americans were not exposed to this latent pool of circulating Eurasian diseases until the European colonization of the Americas, which then led to frequent virgin soil epidemics among Native Americans.[9]

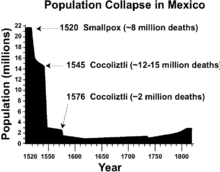

Cocoliztli epidemics

A series of epidemics of unknown origin caused major population collapses in Central America in the 16th century, possibly due to little immunological protection from previous exposures. While the pathogenic agents of these so-called Cocoliztli epidemics are unidentified, suspected pathogenic agents include endemic viral agents, Salmonella, or smallpox.[10][11]

Australian Aboriginal epidemics

The European colonization of Australia led to major epidemics among Australian Aboriginies, primarily due to smallpox, influenzas, tuberculosis, measles, and potentially chickenpox.[12][13][14]

Other instances

With malaria spreading in the Caribbean islands after European-African contact, the immunological resistance of African slaves to malaria in contrast to the immunologically defenseless locals might have contributed to African slave trade.[15]

Novel and rapid-spreading pandemics such as the Spanish flu are occasionally referred to as virgin soil pandemics.[16]

Debate

Research over the last few decades has questioned some aspects of the notion of virgin soil epidemics. David S. Jones has argued that the term "virgin soil" is often used to describe a genetic predisposition to disease infection and that it obscures the more complex social, environmental, and biological factors that can enhance or reduce a population's susceptibility.[8]

Paul Kelton has argued that the slave trade in indigenous people by Europeans exacerbated the spread and virulence of smallpox and that a virgin soil model alone cannot account for the widespread disaster of the epidemic.[17]

The debate, as regards smallpox (Variola major or Variola minor), is sometimes complicated by problems in distinguishing its effects from those of other diseases that could prove fatal to virgin soil populations, most notably chickenpox.[18] Thus, the famous virologist Frank Fenner, who played a major role in the worldwide elimination of smallpox, remarked in 1985,[19] "Retrospective diagnosis of cases or outbreaks of disease in the distant past is always difficult and to some extent speculative."

Cristobal Silva has re-examined accounts by colonists of 17th-century New England epidemics and has interpreted and argued that they were products of particular historical circumstances, rather than universal or genetically inevitable processes.[20][21]

Historian Gregory T. Cushman claims that virgin soil epidemics were not the major cause of deaths due to disease among Pacific Island populations. Rather, diseases like tuberculosis and dysentery were able to take hold in Pacific Island populations that had weakened immune systems because of overworking and exploitation by European colonizers.[22]

Historian Christopher R. Browning writes that "Disease, colonization, and irreversible demographic decline were intertwined and mutually reinforcing" in reference to virgin soil epidemics during the European colonisation of the Americas. He contrasts the rebound of the European population following the Black Death with the lack of such a rebound across most Native American populations, attributing this differing demographic trend to the fact that Europeans were not exploited, enslaved, and massacred in the aftermath of the Black Death like the indigenous inhabitants of the New World were. "Disease as the chief killing agent," he writes, "does not remove settler colonialism from the rubric of genocide".[23]

Following this work, historian Jeffrey Ostler has argued that, in relation to European colonization of the Americas, "virgin soil epidemics did not occur everywhere and ... Native populations did not inevitably crash as a result of contact. Most Indigenous communities were eventually afflicted by a variety of diseases, but in many cases this happened long after Europeans first arrived. When severe epidemics did hit, it was often less because Native bodies lacked immunity than because European colonialism disrupted Native communities and damaged their resources, making them more vulnerable to pathogens."[24]

See also

- Columbian Exchange

- Ecological imperialism

- Influx of disease in the Caribbean

- Seasoning (colonialism)

- Native American disease and epidemics

- Millenarianism in colonial societies

- Cocoliztli epidemics

References

- Footnotes

- ^ a b Crosby, Alfred W. (1976). "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 33 (2): 289–299. doi:10.2307/1922166. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 1922166. PMID 11633588.

- ^ a b Cliff et al, p. 120

- ^ a b Hays, p. 87

- ^ Daschuk, James (2013). Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. Regina: University of Regina Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780889772960.

- ^ Crosby, Alfred W. (1976), "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America", The William and Mary Quarterly, 33 (2), Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 289–299, doi:10.2307/1922166, JSTOR 1922166, PMID 11633588

- ^ a b Alchon, p. 80

- ^ McNeill, William H. (1976), Plagues and Peoples, Anchor Press, ISBN 978-0385121224

- ^ a b Jones, David (2003). "Virgin Soils Revisited". The William and Mary Quarterly. 60 (4): 703–742. doi:10.2307/3491697. JSTOR 3491697.

- ^ Francis, John M. (2005). Iberia and the Americas culture, politics, and history: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Vågene, Åshild J.; Herbig, Alexander; Campana, Michael G.; Robles García, Nelly M.; Warinner, Christina; Sabin, Susanna; Spyrou, Maria A.; Andrades Valtueña, Aida; Huson, Daniel; Tuross, Noreen; Bos, Kirsten I.; Krause, Johannes (March 2018). "Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (3): 520–528. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2..520V. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 29335577. S2CID 256726167.

- ^ Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo (April 2002). "Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 360–362. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010175. PMC 2730237. PMID 11971767.

- ^ Dowling, Peter (2021). Fatal contact: How epidemics nearly wiped out Australia's first peoples. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing. ISBN 9781922464460.

- ^ Hunter, Boyd H.; Carmody, John (July 2015). "Estimating the Aboriginal Population in Early Colonial Australia: The Role of Chickenpox Reconsidered: Aborigines in early colonial Australia". Australian Economic History Review. 55 (2): 112–138. doi:10.1111/aehr.12068.

- ^ Dowling, Peter. “‘A Great Deal of Sickness’: Introduced Diseases among the Aboriginal People of Colonial Southeast Australia,” 1997.

- ^ Esposito, Elena (2015). "Side effects of immunities : the African slave trade". hdl:1814/36118. ISSN 1830-7728.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Carpenter, Connie; Sattenspiel, Lisa (2009). "The design and use of an agent-based model to simulate the 1918 influenza epidemic at Norway House, Manitoba". American Journal of Human Biology. 21 (3): 290–300. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20857. ISSN 1520-6300. PMID 19107906. S2CID 20066083.

- ^ Kelton, Paul (2007). Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast, 1492-1715. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ There is detailed discussion of the difficulty of making this distinction on one continent at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_in_Australia#Unresolved_Issues_in_the_Chickenpox_Debate and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_in_Australia#Smallpox_and_chickenpox:_confused_yet_distinct

- ^ Hingston, Richard G.; Fenner, Frank (1985). "Smallpox in Australia". Medical Journal of Australia. 142 (4): 278. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb113338.x. PMID 3883104.

- ^ Silva, Cristobal (2011). Miraculous Plagues: An Epidemiology of Early New England Narrative. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Rice, James D. (2014). "Beyond "The Ecological Indian" and "Virgin Soil Epidemics": New Perspectives on Native Americans and the Environment". History Compass. 12 (9): 747–757. doi:10.1111/hic3.12184 – via Wiley-Blackwell Journals (Frontier Collection).

- ^ Cushman, Gregory T. (2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World. Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9781139047470.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (February 8, 2022). "Yehuda Bauer, the Concepts of Holocaust and Genocide, and the Issue of Settler Colonialism". The Journal of Holocaust Research. 36 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1080/25785648.2021.2012985. S2CID 246652960. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. pp. 12–13.

- Bibliography

- Alchon, Suzanne Austin (2003), A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 0-8263-2871-7

- Cliff, Andrew David; Haggett, Peter; Smallman-Raynor, Matthew (2000), Island Epidemics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-828895-6

- Hays, J. N. (2005), Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-658-2