A springald, or espringal, was a medieval torsion artillery device for throwing bolts. It is depicted in a diagram in an 11th-century Byzantine manuscript, but in Western Europe is more evident in the late 12th century and early 13th century. It was constructed on the same principles as an Ancient Greek or Roman ballista, but with inward swinging arms and threw bolts instead of stones. It was also known as a 'skein-bow', and was a torsion device using twisted skeins of silk or sinew to power two bow-arms.[1]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/1Views:26 287 297

-

How to ikejime a fish in under 30 seconds

Transcription

History

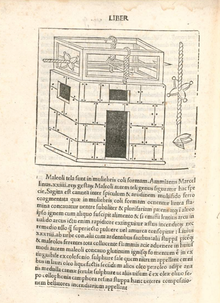

The springald was a defensive bolt thrower based on the torsion mechanism of ancient ballistas, with two arms held in a skein of twisted sinew or hair. Unlike the ballista, it seems to have been housed in a rectangular box-like wooden structure and shot bolts instead of stones. According to digital models and projections, a springald could throw a bolt around 180 meters if mounted on a tower at an elevation of 15 degrees. It appears to have spread across Europe rapidly during the 13th century. According to J Liebel, its appearance may be connected to the invention of the spinning wheel in Europe around 1250, which made the winding of skeins easier. The earliest reference to the springald appears in France in 1249 and its presence is attested to in the arsenal at Reims in 1258. In England, an order of horsehair was made for springalds in 1266. Springalds were commonly used to defend gates from atop towers, where their skeins were safe from wet weather and their bolts could be shot a greater distance. Springalds were expensive to produce: Liebel's calculation for the cost of machines built for the pope at Avignon puts them at six months' wages for an unskilled laborer. By 1382, springalds were being phased out in favor of crossbows or firearms. In some parts of Germany and Switzerland, the springald survived until the early 15th century.[2]

Reconstructions

Several reconstructed examples can be found, Jean Leibell produced a 12-inch (30.5 cm) model for his researches into "Springalds and Great Crossbows" which was commissioned by the Royal Armouries Museum, and a larger model can be seen at the Tower of London. The only known full-size example is in the Royal Armouries Museum at Fort Nelson, Portsmouth at around 8 feet (2.4 m) long and capable of hurling a 2.4 kilograms (5.3 lb) bolt over 55 metres (60 yd) (in excess of its expected range) and a 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb) bolt over 77 metres (84 yd). This example was removed by the manufacturer, The Tenghesvisie Mechanical Artillery Society, for further research into the winding mechanism and firing tests. The machine was to be returned to the museum in the spring of 2013 for a public demonstration of mechanical artillery at Fort Nelson. There also exists or existed a huge springald at Trebuchet Park, Albarracín, Spain.

Size

Although Leibell describes this size of machine as a "Great Springald", it is more likely to be the standard size. If the evidence is investigated, such as the size of the figures in "The Romance of Alexander",[3] where they are at about the height of the top horns, there is no evidence to suggest that they are dwarves, although the length of the bolt to be fired may be a little on the long side.

In popular culture

- An espringal was mentioned in the penultimate episode of Game of Thrones.[4]

- The Redwall book Loamhedge has a mouse named "Springald" (presumably after the contraption).

- Springalds appear in the video game Age of Empires IV.

See also

References

- ^ Nicolle, pp. 173–174, the espringal is depicted, in the form of a fairly detailed diagram, in an 11th-century Byzantine manuscript

- ^ Purton 2006, p. 85-88.

- ^ Bodleian Library, Oxford

- ^ Screenshot from the episode

Bibliography

- Nicolle, David (1996). Medieval Warfare Source Book Vol. II. Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-86019-861-8.

- Purton, Peter (2006). "The myth of the mangonel: Torsion artillery in the Middle Ages". Arms & Armour. 3: 79–90. doi:10.1179/174962606X99155. S2CID 162238792.