Polykleitos (Ancient Greek: Πολύκλειτος) was an ancient Greek sculptor, active in the 5th century BCE. Alongside the Athenian sculptors Pheidias, Myron and Praxiteles, he is considered as one of the most important sculptors of classical antiquity.[1] The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to Xenocrates (the "Xenocratic catalogue"), which was Pliny's guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron.[2] He is particularly known for his lost treatise, the Canon of Polykleitos (a canon of body proportions), which set out his mathematical basis of an idealised male body shape.

None of his original sculptures are known to survive, but many marble works, mostly Roman, are believed to be later copies.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:270 36210 7071 1864 165614

-

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear Bearer)

-

Polykleitos's Doryphoros, ideal beauty in ancient Greece

-

The Doryphorus of Polykleitos

-

The Kanon of Polykleitos

-

Episode 80 - Polykleitos

Transcription

(piano music playing) Steven: What is perfect? Well, the ancient Greeks thought the human body was perfect but, for them, it was not an individual that was perfect. It was almost mathematical precision, where the proportions of every part of the body were perfect in relationship to the others. Beth: We're looking at an ancient Roman copy of a Greek bronze original by the great artist, Polykleitos, who sought out to demonstrate just that. What would perfect ideal beauty be, thinking about the mathematical relationship of each part of the human body to the other, and in relationship to the whole? Steven: This is a sculpture called the Doryphorus. Doryphorus means a spear-bearer, and he would have, originally, been holding a bronze spear. We call it the Doryphorus. Polykleitos apparently called it Canon, not to mean a piece of armament, but a kind of idealized form that could be studied and replicated. That is, a set of ideas that you followed. Beth: The idea that you could create a perfect human form, based on math, was really part of a bigger set of ideas for the Greeks. If we think about Pythagoras, for example, Pythagoras discovered that harmony in music was based on the mathematical relationship between the notes. Steven: In fact, Pythagoras tried to understand the origin of all beauty through ratio and, so, it follows that the Greeks would be looking for that in one of the forms that they felt were most beautiful, that is the human body. The Greeks would perform their athletics nude, celebrating the body and its physical abilities. But, even when they represented figures in noble pursuits, like this figure, we have a figure whose clothes have been taken off. This is not because soldiers went into battle nude in ancient Greece, but because this sculpture is not about warfare. It's not a portrait of an individual. This is a sculpture that is about the perfection of human form. Beth: This was found in a palestra in Pompeii, a place where athletes would work out, perhaps as a kind of inspiration for them. Steven: So, that's another layer of meaning. The Romans loved Greek art, and had it copied in marble very often, and even in a city like Pompeii, we found thousands of sculptures that are copies of ancient Greek originals. This is based on a sculpture that is at the very beginning of the Classical Period, before the Parthenon sculptures, but it's after the Archaic figures, it's after the standing figure that we know as the Kouros. Here, the Greeks have turned away from the stiff renderings that had been so characteristic of the Archaic, and have, instead, begun to examine the human body and understand its physiognomy, This is one of the classic expressions of Contrapposto. Beth: The Doryphorus stands on his right foot, his left leg is relaxed, the right leg is weight-bearing, but the left hand would have been weight-bearing the spear. Similarly, the right arm is relaxed, so there's a sense of counterbalancing and harmony in the composition of the body. Steven: In a Kouros figure, you have both feet firmly planted, although one leg is forward, but, nevertheless, if you were to draw a line between the ankles, they would still be horizontal to the floor. Beth: And, in a Kouros, the figure is symmetrical. Steven: Here, both of those things have changed, and you see that his left ankle is up, and so you have a tilt of that axis, the axis of the knees are tilted in the opposite way. The hips are parallel to the axes of the knees, but also tipped, and then look what happens as a result of that. In those earlier figures, there was a perfect symmetry, and a perfect line that could be drawn down the center of the body. Here, there's a gentle S curve, and you can see, for instance, that his right side is compressed, compared to the left side, because the left hip is literally hanging down over that free leg. It's not being supported. Beth: To complete that sense of balance and harmony, Polykleitos turned the head slightly, breaking that symmetry of the Archaic Kouros figures. With the invention of Contrapposto by the Greeks, in the 5th century BCE, we would have, for the first time in Western art history, figures who seem fully alive, as though they move in the world. They're like us. Steven: This is a sculpture that is, for all of the complexity of what we've just discussed, is simply walking, but the mechanics of the human body walking are incredibly complicated, and here we have a civilization that not only was interested in understanding, through careful observation, how the body moved, but were interested, culturally, in capturing that. We have a society that puts human potential at the center. Beth: And creates figures who are not transcendent, who don't exist in a separate world, but who exist in our world. They're, in a way, ideal mirrors of ourselves. (piano music playing)

Name

His Greek name was traditionally Latinized Polycletus, but is also transliterated Polycleitus (Ancient Greek: Πολύκλειτος, Classical Greek Greek pronunciation: [polýkleːtos], "much-renowned") and, due to iotacism in the transition from Ancient to Modern Greek, Polyklitos or Polyclitus. He is called Sicyonius (lit. "The Sicyonian", usually translated as "of Sicyon")[3] by Latin authors including Pliny the Elder and Cicero, and Ἀργεῖος (lit. "The Argive", trans. "of Argos") by others like Plato and Pausanias. He is sometimes called the Elder, in cases where it is necessary to distinguish him from his son, who is regarded as a major architect but a minor sculptor.

Early life and training

As noted above, Polykleitos is called "The Sicyonian" by some authors, all writing in Latin, and who modern scholars view as relying on an error of Pliny the Elder in conflating another more minor sculptor from Sikyon, a disciple of Phidias, with Polykleitos of Argos. Pausanias is adamant that they were not the same person, and that Polykleitos was from Argos, in which city state he must have received his early training,[a] and a contemporary of Phidias (possibly also taught by Ageladas).

Works

Polykleitos's figure of an Amazon for Ephesus was admired, while his colossal gold and ivory statue of Hera which stood in her temple—the Heraion of Argos—was favourably compared with the Olympian Zeus by Pheidias. He also sculpted a famous bronze male nude known as the Doryphoros ("Spear Bearer"), which survives in the form of numerous Roman marble copies. Further sculptures attributed to Polykleitos are the Discophoros ("Discus-bearer"), Diadumenos ("Youth tying a headband")[4] and a Hermes at one time placed, according to Pliny, in Lysimachia (Thrace). Polykleitos's Astragalizontes ("Boys Playing at Knuckle-bones") was claimed by the Emperor Titus and set in a place of honour in his atrium.[5] Pliny also mentions that Polykleitos was one of the five major sculptors who competed in the fifth century B.C. to make a wounded Amazon for the temple of Artemis; marble copies associated with the competition survive.[6]

Diadumenos

The statue of Diadumenos, also known as Youth Tying a Headband is one of Polykleitos's sculptures known from many copies. The gesture of the boy tying his headband represents a victory, possibly from an athletic contest. "It is a first-century A.D. Roman copy of a Greek bronze original dated around 430 B.C."[4] Polykleitos sculpted the outline of his muscles significantly to show that he is an athlete. "The thorax and pelvis of the Diadoumenos tilt in opposite directions, setting up rhythmic contrasts in the torso that create an impression of organic vitality. The position of the feet poised between standing and walking give a sense of potential movement. This rigorously calculated pose, which is found in almost all works attributed to Polykleitos, became a standard formula used in Greco-Roman and, later, western European art."[4]

Doryphoros

Another statue created by Polykleitos is the Doryphoros, also called the Spear bearer. It is a typical Greek sculpture depicting the beauty of the male body. "Polykleitos sought to capture the ideal proportions of the human figure in his statues and developed a set of aesthetic principles governing these proportions that was known as the Canon or 'Rule'.[7] He created the system based on mathematical ratios. "Though we do not know the exact details of Polykleitos’s formula, the end result, as manifested in the Doryphoros, was the perfect expression of what the Greeks called symmetria.[7] On this sculpture, it shows somewhat of a contrapposto pose; the body is leaning most on the right leg. The Doryphoros has an idealized body, contains less of naturalism. In his left hand, there was once a spear, but if so it has since been lost. The posture of the body shows that he is a warrior and a hero.[4][7] Indeed, some have gone so far as to suggest that the figure depicted was Achilles, on his way to the Trojan War, as a similar depiction of Achilles carrying a shield is seen on a vase painted by the Achilles Painter at around the same time.[8]

Style

Polykleitos, along with Phidias, created the Classical Greek style. Although none of his original works survive, literary sources identifying Roman marble copies of his work allow reconstructions to be made. Contrapposto, a pose that visualizes the shifting balance of the body as weight is placed on one leg, was a source of his fame.

The refined detail of Polykleitos's models for casting executed in clay is revealed in a famous remark repeated in Plutarch's Moralia, that "the work is hardest when the clay is under the fingernail".[9]

The Canon of Polykleitos and "symmetria"

Polykleitos consciously created a new approach to sculpture, writing a treatise (an artistic canon (from Ancient Greek Κανών (Kanṓn) 'measuring rod, standard') and designing a male nude exemplifying his theory of the mathematical basis of ideal proportions. Though his theoretical treatise is lost to history,[10] he is quoted as saying, "Perfection ... comes about little by little (para mikron) through many numbers".[11] By this he meant that a statue should be composed of clearly definable parts, all related to one another through a system of ideal mathematical proportions and balance. Though his Canon was probably represented by his Doryphoros, the original bronze statue has not survived, but later marble copies exist.

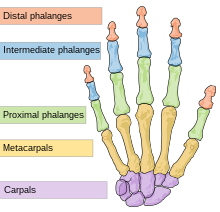

References to the Kanon by other ancient writers imply that its main principle was expressed by the Greek words symmetria, the Hippocratic principle of isonomia ("equilibrium"), and rhythmos. Galen wrote that Polykleitos's Kanon "got its name because it had a precise commensurability (symmetria) of all the parts to one another."[12] He also wrote that the Kanon defines beauty "in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other."[13]

The art historian Kenneth Clark observed that "[Polykleitos's] general aim was clarity, balance, and completeness; his sole medium of communication the naked body of an athlete, standing poised between movement and repose".[14]

Conjectured reconstruction

Despite the many advances made by modern scholars towards a clearer comprehension of the theoretical basis of the Canon of Polykleitos, the results of these studies show an absence of any general agreement upon the practical application of that canon in works of art. An observation on the subject by Rhys Carpenter remains valid:[15] "Yet it must rank as one of the curiosities of our archaeological scholarship that no-one has thus far succeeded in extracting the recipe of the written canon from its visible embodiment, and compiling the commensurable numbers that we know it incorporates."

— Richard Tobin, The Canon of Polykleitos, 1975.[16]

In a 1975 paper, art historian Richard Tobin[b] suggested that earlier work to reconstruct the Canon had failed because previous researchers had made a flawed assumption of a foundation in linear ratios rather than areal proportion.[16] He conjectured that the Canon begins from the length of the outermost part (the "distal phalange") of the little finger. The length of the diagonal of a square of this side (mathematically, √2, about 1.4142) gives the length of the middle phalange. Repeating the process gives the length of the proximal phalange; doing so again gives the length of the metacarpal plus the carpal bones – the distance from knuckle to the head of the ulna. Next, a square of side equal to the length of the hand from little finger to wrist yields a diagonal of length equal to that of the forearm. This "diagonal of a square" process gives the relative ratios of many other key reference distances in the human male body.[18] The process would not require measurement of square roots: the artist could take a long cord and make knots separated from each other by a distance which equals the diagonal of the square drawn on the preceding length.[19] On the body proper, the process is repeated but the geometric progression is taken and retaken from the top of the head (rather than additively, as on the hand/arm): the head from crown to chin is the same size as the fore-arm; from crown to clavicle is as long as the upper arm; a diagonal on that square yields the distance from the crown to the line of the nipples.[20] Tobin validated his calculation by comparing his theoretical model with a Roman copy of Doryphoros in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.[21]

Followers

Polykleitos and Phidias were among the first generation of Greek sculptors to attract schools of followers. Polykleitos's school lasted for at least three generations, but it seems to have been most active in the late 4th century and early 3rd century BCE. The Roman writers Pliny and Pausanias noted the names of about twenty sculptors in Polykleitos's school, defined by their adherence to his principles of balance and definition. Skopas and Lysippus are among the best-known successors of Polykleitos.

Polykleitos's son, Polykleitos the Younger, worked in the 4th century BCE. Although the son was also a sculptor of athletes, his greatest fame was won as an architect. He designed the great theatre at Epidaurus.

Gallery

-

Doryphoros, Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Bronze statue of an athlete from Ephesus cleaning his strigil; 1st century CE copy of a possible original by Polykleitos

-

Pan with flute, Roman copy of a possible original by Polykleitos

Notes

- ^ That a "school of Argos" existed during the fifth century is minimized as "marginal" by Jeffery M. Hurwit, "The Doryphoros: Looking Backward", in Warren G. Moon, ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, 1995:3-18.

- ^ Richard Tobin holds a doctorate in Art History from Bryn Mawr College. Since April 2016, he is director of Harwood Museum of Art at the University of New Mexico.[17]

References

- ^ Blumberg, Naomi. "Polyclitus". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Andrew Stewart (1990). "Polykleitos of Argos". One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Pliny the Elder Natural Histories 34.19.23

- ^ a b c d "Statue of Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia

- ^ "Statue of a wounded Amazon". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Art Through Time: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Greek vases 800-300 BC: key pieces". www.beazley.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Plutarch, Quaest. conv. II 3, 2, 636B-C, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Art Through Time: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

we are told quite unequivocally that he related every part to every other part and to the whole and used a mathematical formula in order to do so. What that formula was is a matter of conjecture.

- ^ Philo, Mechanicus, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ Galen, De Temperamentis.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 163. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Clark 1956:63.

- ^ Rhys Carpenter (1960). Greek Sculpture : a critical review. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 100. cited in Tobin (1975), p. 307

- ^ a b Tobin (1975), p. 307.

- ^ "Tobin appointed director of UNM's Harwood Museum of Art" (Press release). 22 April 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 309.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 310.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 313.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 315.

Sources

- Pausanias (1911) [143-176]. Description of Greece. Translated by W H S Jones. London: Heinman.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Polyclitus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23.

- Tobin, Richard (1975). "The Canon of Polykleitos". American Journal of Archaeology. 79 (4): 307–321. doi:10.2307/503064. JSTOR 503064. S2CID 191362470.

External links

![]() Media related to Polykleitos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Polykleitos at Wikimedia Commons