| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Octamethyl-1,3,5,7,2,4,6,8-tetroxatetrasilocane | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.307 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

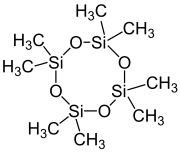

| [(CH3)2SiO]4 | |

| Molar mass | 296.616 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 0.956 g/mL |

| Melting point | 17–18 °C (63–64 °F; 290–291 K) |

| Boiling point | 175–176 °C (347–349 °F; 448–449 K) |

| 56.2±2.5 ppb (23 °C)[1] | |

| log P | 6.98±0.13[2] |

| Vapor pressure | 124.5±6.2 Pa (25 °C)[3] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

[4] [4]

| |

| Warning | |

| H361f, H410 M=10[4] | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, also called D4, is an organosilicon compound with the formula [(CH3)2SiO]4. It is a colorless viscous liquid. It is a common cyclomethicone. It is widely used in cosmetics.[5]

Production and polymerization

Commercially D4 is produced from dimethyldichlorosilane. Hydrolysis of the dichloride produces a mixture of cyclic dimethylsiloxanes and polydimethylsiloxane. From this mixture, the cyclic siloxanes including D4 can be removed by distillation. In the presence of a strong base such as KOH, the polymer/ring mixture is equilibrated, allowing complete conversion to the more volatile cyclic siloxanes:[5]

- [(CH3)2SiO]4n → n [(CH3)2SiO]4

D4 and D5 are also precursors to the polymer. The catalyst is again KOH.

Occurrence

It is among the most important of all the cyclic siloxanes, with a global production volume of 136 million kilograms in 1993.[6] 100,000–1,000,000 tonnes per year of D4 is manufactured and/or imported in the European Economic Area.[7]

Safety and environmental considerations

D4 is of low acute toxicity. The LC50 for a single four hour inhalation exposure in rats is 36 mg/L. The oral LD50 in rats is above 4800 mg/kg and the dermal LD50in rats is above 2400 mg/kg.[8]

As the smallest cyclic dimethylsiloxane that does not experience considerable ring strain,[9] D4 is one of the most abundant siloxanes in the environment, e.g. in landfill gases.[10] D4 and D5 have attracted attention because they are pervasive. Cyclic siloxanes can be detected in some species of aquatic life.[11] An independent, peer-reviewed study in the US found "negligible risk from D4 to organisms"[12] while a scientific assessment by the Australian government stated, "the direct risks to aquatic life from exposure to these chemicals at expected surface water concentrations are not likely to be significant."[13]

In the European Union, D4 was characterized as a substance of very high concern (SVHC) due to its PBT and vPvB properties and was thus included in the candidate list for authorisation.[14][clarification needed] D4 shall not be placed on the market in wash-off cosmetic products in a concentration equal to or greater than 0.1% by weight of either substance, after 31 January 2020.[15] Conversely, a detailed review and analysis of the science by the State of Washington in 2017 led to the removal of D4 from their CHCC listing.[16][clarification needed] That decision prompted the State of Oregon to follow suit in 2018.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Sudarsanan Varaprath; Cecil L. Frye; Jerry Hamelink (1996). "Aqueous solubility of permethylsiloxanes (silicones)". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 15 (8): 1263–1265. doi:10.1002/etc.5620150803.

- ^ Shihe Xu, Bruce Kropscott (2012). "Method for Simultaneous Determination of Partition Coefficients for Cyclic Volatile Methylsiloxanes and Dimethylsilanediol". Analytical Chemistry. 84 (4): 1948–1955. doi:10.1021/ac202953t. PMID 22304371.

- ^ Ying Duan Lei; Frank Wania; Dan Mathers (2010). "Temperature-Dependent Vapor Pressure of Selected Cyclic and Linear Polydimethylsiloxane Oligomers". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 55 (12): 5868–5873. doi:10.1021/je100835n.

- ^ a b "Harmonised classification – Annex VI of Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 (CLP Regulation)". Retrieved 2022-03-15.

- ^ a b Moretto, Hans-Heinrich; Schulze, Manfred; Wagner, Gebhard (2005). "Silicones". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_057. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Philippe P. Quevauviller; Patrick Roose; Gert Verreet (24 August 2011). Chemical Marine Monitoring: Policy Framework and Analytical Trends. John Wiley & Sons. p. 2010. ISBN 978-1-119-97759-9.

- ^ "InfoCard – Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane". ECHA. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ Brooke DN, Crookes MJ, Gray D, Robertson S (2009). Environmental Risk Assessment Report: Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (PDF) (Report). Environment Agency.

- ^ Brook, Michael A. (2000). Silicon in Organic, Organometallic and Polymer Chemistry. New York: Wiley. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-471-19658-7.

- ^ Franz-Bernd Frechen (2009). Odours and VOCs: Measurement, Regulation and Control Techniques. kassel university press GmbH. p. 287. ISBN 978-3-89958-609-1.

- ^ Wang, De-Gao; Norwood, Warren; Alaee, Mehran; Byer, Jonathan D.; Brimble, Samantha "Review of Recent Advances in Research on the Toxicity, Detection, Occurrence and Fate of Cyclic Volatile Methyl Siloxanes in the Environment" Chemosphere 2013, volume 93, pages 711–725, doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.10.041.

- ^ Josie B. Nusz, Anne Fairbrother, Jennifer Daley, G. Allen Burton (2018). "Use of multiple lines of evidence to provide a realistic toxic substances control act ecological risk evaluation based on monitoring data: D4 case study". Science of the Total Environment. 636: 1382–1395. Bibcode:2018ScTEn.636.1382N. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.335. PMID 29913599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cyclic volatile methyl siloxanes: Environment tier II assessment" Archived 2020-05-27 at the Wayback Machine Australian Department of Health. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ "Candidate List of substances of very high concern for Authorisation – Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane". ECHA. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ "Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/35 of 10 January 2018 amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane ('D4') and decamethylcyclopentasiloxane ('D5')". Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ "Concise Explanatory Statement: Children's Safe Products Reporting Rule" State of Washington Department of Ecology. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ "Notice of Proposed Rulemaking" State of Oregon. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

External links

- Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, silica reaction product in the Consumer Product Information Database

- Octamethylcydotetrasiloxane (a misspelling) in the Consumer Product Information Database