The nitrone-olefin (3+2) cycloaddition reaction is the combination of a nitrone with an alkene or alkyne to generate an isoxazoline or isoxazolidine via a (3+2) cycloaddition process.[1] This reaction is a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, in which the nitrone acts as the 1,3-dipole, and the alkene or alkyne as the dipolarophile.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/3Views:2 1189689 533

-

Example: [3+2] CYCLOADDITION:1,3-DIPLOE & DIPOLEPHILE MECHANISM

-

An Efficient Synthesis of Tetrodotoxin

-

Mod-01 Lec-32 1,3 Dipolar Cycloaddition - I

Transcription

Mechanism and stereochemistry

When nitrones are combined with either alkenes or alkynes, (3+2) cycloaddition leads to the formation of a new C–C bond and a new C–O bond. The cycloadditions is stereospecific with respect to the configuration of the alkene; however, diastereoselectivity in reactions of C-substituted nitrones is often low.[2] Regioselectivity is controlled by the dominant frontier orbitals interacting during the reaction, and substrates with electronically distinct substituents tend to react with high regioselectivity. Intramolecular versions of the reaction have been used to synthesize complex polyclic carbon frameworks. Reduction of the N–O linkage leads to 1,3-aminoalcohols.

The (3+2) cycloaddition itself is a concerted, pericyclic process whose regiochemistry is controlled by the frontier molecular orbitals on the nitrone (the dipole) and the dipolarophile.[3] When R' is an electron-donating group, alkyl, or aryl, the dominant FMOs are the HOMO of the dipolarophile and the LUMO of the nitrone. Thus, connecting the atoms whose coefficients in these orbitals are largest, the 5-substituted isoxazolidine is predicted to predominate. On the other hand, when the dipolarophile is electron poor, the HOMOnitrone-LUMOdipolarophile interaction is most important, and the 4-substituted product is favored.

Scope and limitations

Alkyl and aryl terminal alkenes react with high regioselectivity to give 5-substituted isoxazolidines. This outcome is consistent with frontier molecular orbital (kinetic) control of the distribution of isomers: the nitrone oxygen, which possesses the largest orbital coefficient in the HOMO of the nitrone, forms a bond with the inner carbon of the alkene, which possesses the largest orbital coefficient in the LUMO of the alkene.[4]

The configuration of 1,2-disubstituted alkenes is maintained in the products of cycloaddition. Consistent with FMO control of the reaction, the more electron-withdrawing substituent on these substrates ends up in the 4 position of the product. Put another way, the carbon with the largest LUMO coefficient in the dipolarophile (distant from the electron-withdrawing group) forms a bond with the nitrone oxygen, which possesses the largest HOMO coefficient in the nitrone.[5]

Alkynes can also serve as dipolarophiles in this reaction. The rules for predicting alkene cycloaddition products based on the relevant FMOs apply to substituted alkynes as well—electron-poor alkynes tend to give 4-substituted products, while electron-rich, alkyl, and aryl alkynes give 5-substituted products.[6]

Intramolecular variants of the reaction are very useful for the synthesis of complex polycyclic frameworks. These reactions generally take place at much lower temperatures than intermolecular cycloadditions. Regiochemistry is more difficult to predict for intramolecular reactions: either bridged or fused products can result, and both cis- and trans-fused rings are possible.[7]

An existing stereocenter in the tether between the alkene and nitrone often leads to the generation of a single diastereomer of product. In this example, the bulkier phenyl substituent ends up on the exo face of the bicyclic ring system.[8]

Synthetic applications

Synthesis of (±)-lupinine

2,3,4,5-Tetrahydropyridine-1-oxide can be used for the construction of fused heterocycles in alkaloids and other natural products. A synthesis of (±)-lupinine uses a ring-expanding rearrangement of a mesylate, providing rapid access to the target.[9]

Synthesis of hydroxycotinine

The structure of hydroxycotinine, a human metabolite of nicotine, was confirmed via an independent synthesis employing nitrone-olefin cycloaddition.[10]

Synthesis of (+)-porantheridine

Rearrangement of a (3+2) cycloadduct provides (+)-porantheridine.[11] The cycloadduct is subjected to hydrogenation, acid hydrolysis, oxidation, basic hydrolysis, and cyclization to give the target.

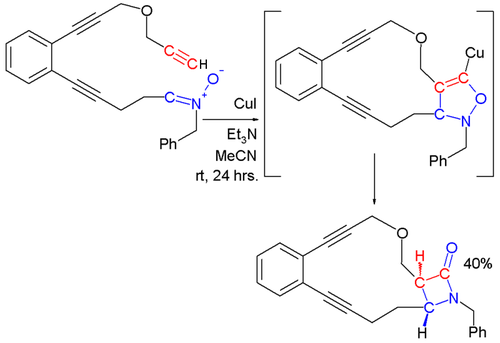

Kinugasa reaction to form β-lactams

In the Kinugasa reaction, a nitrone and a copper acetylide react to ultimately form a β-lactam.[12][13] In the first step of this reaction, a metal acetylide is formed by reaction of the terminal alkyne with the copper salt. The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the nitrone with the metal acetylide affords a 5-membered ring that rearranges to form a β-lactam.

Other reactions

Another example of a (3+2) cycloaddition is that in which a Baylis-Hillman adduct is the dipolarophile. This reacts with C-phenyl-N-methylnitrone to form an isoxazolidine.[14]

References

- ^ Confalone, P. N.; Huie, E. M. Org. React. 1988, 36, 1. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or036.01

- ^ Tufariello, J. J.; Ali, S. A.; Klingele. H. O. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 4213.

- ^ Houk, K. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 8953.

- ^ Huisgen, R.; Hauck, H.; Grashey, R.; Seidl, H. Chem. Ber. 1968, 101, 2568.

- ^ Joucla, M. Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 2315.

- ^ Winterfeldt, E.; Krohn, W.; Stracke, H. Chem. Ber. 1969, 102, 2346.

- ^ LeBel, N. A.; Post, M. E.; Whang, J. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3759–3767. doi:10.1021/ja01072a031

- ^ Vinick, F. J.; Fengler, I. E.; Gschwend, H. W. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 2936.

- ^ Tufariello, J. J.; Tegeler, J. J. Tetrahedron Lett., 1976, 4037–4040. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92569-3

- ^ Dagne, E.; Castagnoli, Jr., N. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 356–360. doi:10.1021/jm00274a005

- ^ Gossinger, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 2229.

- ^ The reactions of copper(I) phenylacetylide with nitrones Manabu Kinugasa and Shizunobu Hashimoto J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1972, 466 - 467, doi:10.1039/C39720000466

- ^ A novel synthesis of β-lactam fused cyclic enediynes by intramolecular Kinugasa reaction Runa Pal and Amit Basak Chem. Commun., 2006, 2992 - 2994, doi:10.1039/b605743h

- ^ Diastereoselectivity of Nitrone 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition to Baylis-Hillman Adducts Branislav Dugovič, Lubor Fišera, Christian Hametner and Nada Prónayovác. Arkivoc 2004 BS-834A Article