| Healthcare in the United States |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States |

|---|

|

|

The healthcare reform debate in the United States has been a political issue focusing upon increasing medical coverage, decreasing costs, insurance reform, and the philosophy of its provision, funding, and government involvement.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:4 5647057 2371 093924

-

Health Care Reform Debate

-

Health Care Reform: "The Debate"

-

The Forum: The Debate over Health Care Reform

-

Health Care Reform: The Supreme Court Debate

-

The Impact of the 2010 Elections on U.S. Healthcare Reform

Transcription

Hello, thank you for being here today, for discussion slash debate on healthcare in America. We've got a couple great speakers today, leaders in their field. But before we get started, I want to announce a couple other events that we have coming up. On April 1st, Professor Patrick Geary will be here to discuss the separation of church and state, and on April 20, former Solicitor General of Texas, the Honorable James C. Ho will be here to discuss the pros and cons of birthright citizenship. So I hope all of you can make it for that as well. I also like to thank Andy Albertson and Michelle Pang for helping to put this event together, and the Federal Society National Organization for their support, as well as the John Templeton Foundation for their special funding for today's event and for the lunch. I'd also like to thank Professor Tachikawa, who's traveled here from Japan, probably for the pizza, like most of you. But thank you for being here, Professor. I guess before we get started, the way that this event will happen, both speakers, or each speaker will take twelve minutes to present their side of affordable care or Obamacare, and each will have six minutes to rebut the other's presumptions and premise. So to get started, let me introduce our speakers. We have Ilya Shapiro with the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., by way of Canada and Russia. Mr. Shapiro is-- Ilya Shapiro: And Mississippi. And Mississippi. Mr. Shapiro is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute and editor-in-chief of the Cato Supreme Court Review. Before joining Cato, Mr. Shapiro was a special assistant and advisor to the Multi-National force in Iraq on rule of law issues and has practiced privately in international, political, commercial, and antitrust litigation. He's a regular contributor to a variety of media, including the Washington Times, the LA Times, National Review online, The Daily Show, or excuse me, The Colbert Report, Comedy Central, CNN, Fox News, et cetera. Mr. Shapiro will be arguing in favor of the Constitution, liberty, freedom, and all things sacred. Not all things sacred. I only have 12 minutes. 12 minutes. 12 minutes' worth of all things constitutional. Professor Leflar, our very own Professor Leflar here, is a leader in his field as well. Professor Leflar teaches an introductory torts class as well as health policy, bioethics, products liability, and a variety of other topics. Professor Leflar's CV is also extensive, and we all know he is an institution here at Arkansas. So please, help me welcome our speakers today, and at the conclusion of their presentations we'll open it up for questions to the audience. [ Applause ] Mr. Shapiro -- I'm sorry, Professor Leflar, you'll go first. I'm gonna move over here so I can see his slides. Well, thank you, Josh. Thanks to the Federalist Society for putting on this event, and to our distinguished guest, Mr. Ilya Shapiro, for coming to Fayetteville. He had to come through bad weather, a long delay in Chicago last night, and he got here for this healthcare reform debate. We really appreciate your presence here. Mr. Shapiro is clearly one of the nation's foremost and well-known critics of the new healthcare law. He speaks at law schools around the country. He's written friend of the court briefs attacking the law, and he's also an advocate at the state level. In fact, this January he submitted testimony in favor of some unsuccessful legislation right here in Arkansas, to take Arkansas out of the individual mandate. That was a bill officially titled the Arkansas Healthcare Freedom Act, but which might better have been labeled the Arkansas Healthcare Freeloaders Protection Act. And I'm going to have more to say about healthcare freeloaders in a few minutes. Healthcare reform is a pretty complicated subject to cover in a single hour, much less 12 minutes, but here's how I'm going to try to do it. I'm going to -- my first turn I'm going to speak to the merits of the new law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which I will call by its acronym, PPACA. And first, since its content has been so widely misrepresented and misunderstood, I'm going to briefly set out the facts about what the law does and what its impact on Arkansas are going to be. Second, I'm going to address what everybody wants to hear about, the part of the law that says, come 2014, people have to have health insurance or pay a penalty or a tax. And I'll explain why that makes sense in terms of both ethics and economics, and why people like Mr. Shapiro, who want to repeal it or strike it down, are really lobbying and lawyering on behalf of the irresponsible freeloaders who want to foist most of their healthcare expenses on the rest of us. And then third, and this will probably come in my second turn up, I'll speak to the constitutional litigation over the law as to which Mr. Shapiro is much more of an expert than I am. Now, here's how the Federalist Society publicized this debate around the law school at least, and I love this. I think it's hilarious. And I see a lot of law students here, so I guess it must have been a pretty effective marketing tactic as well. But let's get real. Here is what PPACA actually does. As most of you know, it has no socialism whatever in it. We are not setting up a national health service where most doctors work for the government, as they do in Britain. In fact, what we've got is an imperfect but more or less intelligent set of middle-of-the-road policies, many of which the Republicans themselves used to espouse before the Tea Party days. So the first thing that this law does, is it goes most of the way toward addressing the worst disgrace of American healthcare, the fact that about 50 million Americans don't have health insurance. The law doesn't get us all the way there. It only reaches about two-thirds, or not quite two-thirds of the uninsured. So we still won't have caught up with western Europe or Japan or Taiwan or Australia or Canada, which all have universal coverage. But it does get us most of the way there. In expanding coverage, the emphasis is on primary care, preventive care, family medicine, the kind of care that will save hospital bills in the long run. PPACA outlaws the cruelest practices of the health insurance industry, practices like yanking away your insurance if you develop a medical condition and need care, or saying, sorry, you've reached your annual limit or your lifetime limit, and we're not going to cover the expensive surgery or the chemotherapy that you need, or hiking premiums to unconscionable levels for people with medical needs. Every other country, every other advanced country, bans those practices and now, finally, America does, too. PPACA sets up an organized marketplace called the Exchange. So people who don't get insurance through Medicare, Medicaid, or their employer, can comparison shop for their insurance through private companies. The idea is like going to Expedia or Travelocity to get your air tickets or your hotel. You go to the Exchange for your health insurance, and it's open both to individuals and to small businesses. This is capitalism in action. It's better organized and better regulated, so consumers and small businesses don't get screwed on individual and small group policies, like is so common now. Now, expanding coverage to 32 million Americans who don't have it, costs a lot of money -- roughly a trillion dollars over ten years at a time of serious concern about the national deficit. But that cost is paid for. Who pays? Well, most of the revenue comes from the wealthy people, couples that make over 252 thousand a year. They get a zero point nine increase, nine percent increase in Medicare withholding, a two point nine percent increase in unearned income tax; also, the companies that will benefit from all the new customers; the drug companies, the medical device companies, the health insurance industry, they have to pay in. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that in the long run, this bill is better than revenue neutral. It reduces the deficit. According to the CBO, scrapping the law would have the effect of piling on more red ink by far onto the federal budget. This law is not perfect. It contains many a compromise, like any complex law. But, I think it moves America in the right direction toward giving every American the right to at least a fair basic level of healthcare. Now, the Arkansas impacts. The law's nationwide benefits are evident, but the law disproportionately helps states like Arkansas that have relatively low income and lots of small employers. Most Arkansans in the private sector work in small businesses or for themselves, and most of them don't have health insurance as a job benefit. Now, here's how Arkansas compared with the rest of the country on health insurance through employment in 2005, and the numbers are quite a bit lower now, in 2011. A lot of people have lost their employment coverage. So, people have to go to the individual market, where premiums are much higher. You get a worse deal for your money, if you can afford it at all, and the insurance companies often yank the rug out from under you when you need care the most. Mr. Shapiro, we've got more than half a million uninsured working-age people here in Arkansas, and most of those uninsured people, two-thirds of them, are not unemployed; they're not welfare recipients. These are people in families with full-time workers. So you might say, well, hey, they can always go to Medicaid's, get their healthcare that way. Well, if you think that, sir, you would be wrong. It's true that three-fifths of Arkansas children do get their healthcare through Medicaid, through our Our Kids program. But, among adults, care for the blind and disabled, you only qualify for Medicaid in Arkansas if you have income less than seventeen percent of the federal poverty level. And for a family of four, that amounts to 3,750 dollars -- not per month; per year. So in Arkansas, if you're an adult and you have an income, your family of four has an income of 4,000 per year, Mr. Shapiro, you are too rich to qualify for Medicaid. Now, the health reform law is going to change all that. Instead of qualifying for Medicaid at seventeen percent of federal poverty, it's going to be 133 percent nationwide, about 29,000 dollars for a family of four. Now, there'll be federal assistance with premiums for people with incomes above 29,000 dollars on a sliding scale. So basic preventive care, affordable care, is going to be available to almost everyone. Right now, five out of eight bankruptcies in the country are linked to medical bills. Under PPACA, that will largely be a thing of the past. Now, we come to the most controversial part -- the individual mandate. And first, I'm going to explain exactly what that is; and second, I'm going to explain why it's there; third, I'll point out why Mr. Shapiro's solution, trash the mandate, would simply protect healthcare freeloaders and would undercut the whole structure of the law because of the operation of the vicious cycle of adverse selection. Now, here's what the law actually provides. First of all, U.S. citizens, legal residents, have to have healthcare coverage starting in 2014 or else they have to pay -- you can call it a tax, a penalty, whichever. The amount of that is about 700 a year, up to a max of 2,100 per family or two and a half percent of household income. Note that that's a lot less than you got to pay for healthcare insurance. That's how you can have the choice to go and pay that penalty instead. And the penalty phases in starting with 95 bucks in 2014, and then up to the rest of it in 2016. Now, so what you see is that mandate is really the wrong word, because you can choose to pay the penalty. Insurance is not compulsory. That's a point that critics of the law generally don't point out. So what it is really is play or pay. It's your choice. But as an ethical matter, people ought to play even if paying the penalty saves them money. And here's why. For me, the point is personal responsibility. None of us can tell when we're going to be in a car crash or come down with cancer or some other expensive chronic illness that we don't have the personal resources to pay for, unless we're Bill Gates or somebody like that. Choosing not to buy health insurance that'll cover the cost you can't afford if you fall ill is the ethical equivalent of choosing not to buy the vehicle liability insurance that'll cover the cost you can't afford if you hit somebody. Simple as that. Well, you might say even if I don't buy health insurance, I can always go to the emergency room; get care there. Well, that's true, thanks to the federal anti-dumping law. And lots of people do. More than half the acute doctor care visits made by patients without health insurance were to emergency rooms. But that's expensive, and that's not as good as regular primary care. You're missing the preventive care that would have detected the cancer or the heart disease, so you wind up with expensive hospital care and unnecessary illness and preventable death. And who pays for that expensive hospital treatment that could have been avoided by proper preventive care? Well, the uninsured do pay for some of it -- about a third. And the rest is paid by government, by charity, by cost-shifting to insured patients; in other words, by the rest of us. We all pay for it through higher premiums and taxes. So the people who don't buy health insurance are foisting their bad luck or their failure to take care of themselves on the rest of us. They're freeloaders. It's irresponsible. And this is the point that Republicans in the 1990's healthcare debate understood full well. This is the point that Republican Governor Mitt Romney of Massachusetts fully understood when he put through that state's reform, including the individual mandate. It's the point that Senator Charles Grassley, ranking Republican member of the Finance Committee in the Senate, fully understood in his negotiations over PPACA. Mr. Shapiro, I always believed that Libertarians did for individual responsibility, but when you support the Arkansas Healthcare Freedom Act, when you seek the repeal or overturning of the individual mandate, then what you're doing is you're protecting the freeloader's right to burden the rest of us with their risks. As Governor Romney said when he signed the Massachusetts law, a free ride on the government is not libertarian. So here's the point. The ethical policy recognizes that we all need healthcare; everybody should chip in. Those that have a hard time paying for all the premiums, well, we'll help them out to some extent. I think that's the right thing to do. And Mr. Shapiro, I respect your right to disagree, so have at it. I'll talk about the rest of these points on my second turn up. [ Applause ] Well, thanks very much for having me. I don't have any PowerPoint slides. In fact, I consider PowerPoint to be unconstitutional, and I hope all of you are enjoying your pizza. I know that's why at least the law students among you are here, and I appreciate that. I remember being a law student. Enjoy it while it lasts, because at some point in future you might have to have salads for seven days before you're allowed to purchase a pizza, or something like that. And also, it's very interesting having this debate at the University of Arkansas, where my debate opponents name is on the law school, his father, but still, it's a little intimidating, and of course, the place where the Clintons were on the faculty. Now, I was in high school when HillaryCare was the issue. A lot of you, I guess, were in elementary school. I barely remember what the issue was, but I thought, I'm thinking about the Democratic primaries this last time around, and I thought that the Democrats did not choose the candidate that wanted to have the trillion-dollar bailout of insurers and pharmaceutical companies, impose all this complicated new regulation and whatnot. Maybe Hillary was elected, after all. We kind of live in a bizarre universe. But look, I'm a simple constitutional lawyer. I don't have the healthcare policy expertise or healthcare law expertise that Professor Leflar does. In fact, I'll stipulate to every policy argument and healthcare regulatory argument that he wants to make. You want to debate alternatives, policy alternatives to ObamaCare, ask my colleague, Michael Cannon or Mike Tanner or any number of people across the country who specialize in this sort of thing. This debate is not about healthcare; it's about the Constitution. It's about the first principles under which we live. It's about whether our federal government is one of delegated and enumerated and therefore limited powers, or one of a general police power, like the states have. I'm sure one of the few things that Professor Leflar and I will agree on here is that the status quo is not acceptable; the horror stories about Arkansas children being covered and making 4,000 dollars a year -- all of that, that's bad. We shouldn't have a situation where that's the case. The technical legal term for our existing pre-Obama care system is that it sucks. That's the term of art that I would use. Now, that doesn't mean that anything to replace it is either good policy or constitutional, and of course, those are two separate questions. And it doesn't mean that the only alternatives are status quo, universal government single payer, or ObamaCare. There are plenty of different policy proposals that have been on the table. You can read Cato. If you don't like Cato, you can read other people. There's different ways of reaching the goals of accessibility and coverage and cost control and all these different things. We have a very perverted system. Nowhere in the world has your healthcare been tied to your employer. That's dumb. It's an accident of history, because we had wage and price controls during World War II, and employers to compete for workers, started offering perks because they couldn't increase salaries, and one of those perks was healthcare. And that's where it was built; get rid of that tax incentive for employers to do that and you'll have a much more robust system for people to buy health insurance, just like they buy car insurance. Your car insurance isn't tied to your employer; why should your health insurance be? Which raises the point about the mandatory car insurance, just to get that off the table. Two things there. First of all, it's states that impose that requirement on you, not the federal government. Again, states have police powers to legislate for the health, safety, and welfare and morals of their populace; federal government doesn't, gets its powers, the enumerated, 18 enumerated powers in Article I Section 8 of the Constitution. This is Cato Constitution, by the way. It's a two-for; you buy the Constitution, you get the Declaration of Independence for free. And secondly, if you don't drive, or if you don't drive on public roads, you don't have to buy car insurance, though. It's uncontroversial that driving is a privilege, not a right, and it's a choice. Requiring, states requiring someone to buy health insurance because they choose to drive is very different from the federal government requiring you to buy health insurance because you're alive. And I'm glad that all of you are here. I'm glad of the -- heartened by the continued sustained interest in this debate across the country and the commentary and the e-mail exchanges that I have, because you're clearly showing that you're wiser than Nancy Pelosi, who was asked what she thought about the constitutional concerns, and the response of course, was, are you serious? Because the Constitution is the last refuge of the scoundrel that doesn't have any policy arguments to make. We're in a post-constitutional world, where Congress doesn't have any limits, other than what it judges is in the general welfare. As John Conyers called it, the good and welfare clause; if Congress thinks it's good, then it's obviously constitutional, unless it makes the argument that it infringes one of these so-called fundamental rights that take, five judges take a vote on the Supreme Court and then it becomes fundamental, and so forth. And that's why this debate is about federal power rather than individual rights, because the Court's jurisprudence forecloses a lot of the type of freedom of contract and economic liberties and so forth, arguments that could be made on the right side. Now, on the power side, I was heartened to see if any of you have read, skimmed at least, Judge Vincent's decision in the Florida case last month, the 26-state lawsuit. There are now 28 states challenging ObamaCare. Those 26 down there are plus Virginia on its own, Oklahoma on its own. That's unprecedented. There's a lot of things unprecedented about this case, but it's unprecedented to have a majority of states suing the federal government for something like this, on a fundamental piece of domestic legislation. But you look at the beginning of Judge Vincent's opinion. Before you even get into the legal analysis, and he quotes from my favorite part of the Federalist papers, or maybe any part of political theory. Federalist 51, right. If men were angels, we'd live in Utopia; we don't need a constitution; we don't need anything; everybody's happy. If angels ruled over men, fine; we'd have perfect government, good. Again, don't need a constitution, everything, we'd go about our lives, but the angelic government would do everything right. But in the real world, where it's men governing men, we first have to empower the government to govern in certain legitimate areas, and then check it. Right, that's our whole theory. That's our whole basis on which this republic was founded; checks and balances, separation of powers, federalism. All these different concepts stem from the idea that we don't trust the government. Yes, we need it, because the Articles of Confederation wasn't working; we need a central government to protect the national defense, to regulate interstate commerce. Wait, what does that mean? To make commerce regular. It turns out that states were putting up all sorts of protectionist barriers to trade among themselves under the Articles of Confederation. So clearly, we need a federal government to strike down those barriers. That's the basis of the Commerce Clause. It wasn't an authorization for Congress to start regulating. That's changed; that's shifted, but the original conception of the Constitution, one that survived even through modern doctrine, is that we are a government, the Congress, the federal government has limited powers, and it can't go beyond those. There has to be some limiting principles that's left. The other powers are retained by the states and the people. If the individual mandate at least -- there are other claims against ObamaCare -- but if the individual mandate is allowed to stand, ladies and gentlemen, then there are no principled limits left on federal power. You throw out the Constitution, and you leave it to Congress checking itself. You throw out checks and balances, courts have no role because we have to defer to Congress, and it's wise judgment of what its own powers are. Because what is the government's theory? That two courts have accepted, right, the kind of score -- this isn't how we do law -- but the score in the district courts are that two went for the government; two went for the challengers, right, and those are now up on appeal. But the government's theory that these two courts have accepted was that the decision not to purchase health insurance is an economic one, that in the aggregate has a substantial effect on interstate commerce. Well, that's not a limiting principle, because anything -- the decision to do or not do, buy or not buy, anything, is an economic decision that in the aggregate has a substantial effect on interstate commerce. My decision to fly here yesterday, my decision to not go to Starbucks today; your decision to go to law school. What's more related to interstate commerce than your decision to go to law, your choice of a profession? We have a big immigration problem, right, so why don't we with one fell swoop solve that and solve the problem of us having a too litigious society by saying, this half of the room, you no longer can go to law school; you have to be gardeners, and this half has to be bus boys and then we deport all the immigrants, and all these problems are solved, because Congress can regulate these economic decisions that you're making. These are affirmative economic decisions. This isn't sometime in the future that you'll need healthcare. You're already in law school affecting the interstate economy. This goes beyond anything that Congress, the federal government, has ever tried to do. Never, I repeat never -- and the CBO in 1994, when it was evaluating HillaryCare, said this originally; don't take it from a Libertarian think tank or what have you -- never has the federal government required people to buy a good or service under the guise of regulating commerce. It's unprecedented. Think about the foundational commerce clause cases, right. Wickard versus Filburn in 1942, the Agricultural Act setting quotas for farmers to meet, grow their crops and they have to take them to market. And this one farmer wanted to consume his wheat on his farm and not take it to market, and he was set upon by federal agricultural agents and eventually fined. The Court okayed that, because if all the farmers who are engaging in this sort of economic activity of farming did this and didn't meet their quotas, didn't bring it to market, then that would have a substantial effect in the aggregate on interstate commerce. But nobody had to buy wheat. You could see Congress wanted us to support the wheat farmers or have wheat provision; everybody has to buy wheat. Well, nobody had to become farmers. Fast forward to the '60s, the Civil Rights Act, or the Civil Rights era, the Court decisions that if you run a hotel, you run a restaurant, you have to serve people without regard to race and other various protected classes. But nobody has to become a hotelier or restaurateur. And individuals in and of themselves are not economic enterprises. Fast forward again to 2005, the most recent Commerce Clause case. We move from wheat to weed, right, medicinal marijuana, the Raich case. There, under the Controlled Substances Act, the national regulation of drugs, Congress wanted to come in and shut down the personal growth and consumption of marijuana for medicinal uses -- legal under California law, under the state law. And the Court okayed that, because they were engaged in economic activity, growth and consumption, and if everybody did this, then that would foil the again, the national regulatory scheme. But never under the guise of regulating Commerce, having a national scheme, has Congress required people to engage in economic activity, to go into the private marketplace and buy a particular product. This is very different from single payer; this is very different from Medicare, which would be less problematic, and probably under modern doctrine not problematic as a matter of constitutional law -- as opposed to policy, which is a separate discussion, and then you don't want me here, because I'm not a healthcare expert. I'm a constitutional lawyer. Whatever Congress does, whether it's good policy or bad policy, it's a separate question of wherever it has -- whether the Constitution grants it power to do that. Okay, so the Commerce Clause, as I said, you can't justify it that way. This goes beyond the activity, inactivity, distinction. Just calling it an economic decision swallows the hole that doesn't leave any sort of limiting principle. Well, what about the necessary and proper clause, right, because Congress not only gets to regulate commerce and establish post offices and raise armies, but it also gets to do things that are necessary and proper for exercising those other enumerated rights -- enumerated powers; excuse me. Well, it turns out that what we think of as the Commerce Clause doctrine, the substantial effects test, the outermost bounds, under Raich, under Wickard, whatever the collected wisdom, as cabined by Lopez and Morrison, the short-lived federalism revolution, as I call it, failed insurrection -- that already discounts for the necessary and proper clause. You can't just, as Chief Justice John Marshall said, you can't just build inference upon inference and have this infinite causal chain. This is necessary to execute this, which is necessary to execute this, which is necessary to execute this. Going back to Wickard and the cases from the New Deal in the '40s, Darby and LRB, all these foundational cases, they cite McCulloch versus Maryland; they don't cite Gibbons versus Ogden. They weren't a redefinition of Commerce. They were a redefinition of what it means to be necessary and proper, that you can effect, regulate local activity when it has a substantial effect. And so you don't get a further necessary and proper extension; that's already included there. Moreover, Congress can't create its own necessity. It can't rub Aladdin's lamp and wish for infinite wishes, which is what the argument here is, right, because you can imagine some sort of national regulation, be it of healthcare, be it of the auto industry, be it of the housing industry, which would only work if -- insert your weird thing, the housing market collapses, so in future, everybody has to buy a Fannie Mae approved certain type of mortgage; you can't buy a house any other way, to protect our national system of housing market. The next time the auto industry is in jeopardy, we have a regulation that works only if people are required to buy a Chevy -- setting aside the issue of the government owning GM and whatnot. The same thing here. There's a fundamental difference between having the power to regulate an industry -- here, the healthcare industry, requiring coverage of this and that, having certain accounting principles; in the auto industry, seatbelts requirements, fuel emission standards -- and requiring you to buy that industry's product. That's a qualitatively different thing. So just because a 1944 case said for the first time -- and nobody's disputing this; nobody's challenging this, because who's attacking ObamaCare -- said for the first time that Congress can regulate insurance, whereas before it couldn't. Nobody's attacking that, but just because Congress can do that does not follow that then Congress can do anything that has the word healthcare or health insurance in the bill. And finally, it's been justified -- well, I'll finish with the proper prong of necessary and proper. If you're curious or Professor Leflar raises the taxing power issue, I think that's a red herring, because this is a penalty. Obviously when I tell you to do something, I'm not taxing you; I'm mandating, I'm commanding that there's separate issues; but why this isn't a tax, if it were a tax, why it's unconstitutional, et cetera, we can get into that if you're interested. No court has accepted this theory than the ones that ruled for the government. But on the proper prong of necessary and proper, just like the federal government cannot commandeer state officials to do their bidding -- and for the first time in 1992 the Court held this; there was never a state commandeering decision under the Commerce Clause or Tenth Amendment before then -- this violates the proper prong of necessary and proper, because again, there would be no limiting principle on federal power, it destroys federalism, and Congress can't just go around commanding people to do things under the guise of regulating commerce. It can in certain narrow contexts. We know what mandates we have from the federal government -- serving our federal juries, filing and paying your income taxes, registering for selective service and being drafted. Of course, these are tied to selective, explicit exercises of enumerations of power, not Congress exercising a power in some way to regulate commerce and then tying it to that. So if this is allowed to stand, then we throw away the Constitution. I guess I'm out of a job, because there's nothing to argue about any limits or anything, and it's not the republic that I recognize even learning about even in my grade school in Canada. So thank you. [ Applause ] So Mr. Shapiro's passion carried him a little bit longer. We'll give you a few extra minutes. No, that's fine. Thank you. I'm going to begin by confessing that I'm no expert on constitutional law. I'm not a constitutional lawyer, and Mr. Shapiro is far better grounded than I am in the arguments and the precedents. So what I'd like to do here then as an amateur on that field, I'd like to share with you a general and admittedly sketchy outline of what some of the country's leading constitutional law scholars who favor PPACA are writing. None of this is original on my part, but it does link to what I think is at least a sensible and defensible view of our constitutional structure. Mr. Shapiro said this debate is not about healthcare; it's about the Constitution. Well, it's about both. It's about whether the elected Congress has the power to, through the democratic process, try to fix these difficult problems of the healthcare system's serious deficiencies. And my position is that the PPACA should be upheld as constitutional for two principled reason, quite apart from the substantive merits or flaws of the law. First of all, the voters of the United States elected Obama and the democratic Congress in November of 2008 to get healthcare reform done. And the legislative process was a spectacularly intricate and delicate one, but ultimately they did the job. This is how a republic works. No one is saying that Congress passed that law by any kind of illegitimate procedure. They didn't; they followed the rules. And for unelected federal judges, to strike down this law, at the least would be a profoundly disturbing invasion of the democratic process. But Mr. Shapiro and his allies say Congress overstepped the constitutional bounds here. He suggested that well, healthcare reform really does need to happen; coverage really does need to be expanded. Well, so how are we going to accomplish that? Are we going to let the states do it? Are we going to let the states finance it because Congress doesn't have the power to do what it did? My response is that this is a critical national problem, not one the individual states can handle, especially states like Arkansas. And our constitution is explicitly designed to give Congress the tools to address national problems. Now, let's break it down into the Constitution's specific grants of Article 1 powers. As Mr. Shapiro pointed out, there are some different relevant provisions in Article 1 Section 8. One is of course the power to lay and collect taxes to provide for the general welfare of the United States. One is the power to regulate Commerce among the several states, and then the power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers. Now, regarding the taxing power, I'm not going to argue very much with Mr. Shapiro over that. There's little question that if Congress had enacted a law instituting for example, a single payer system like Canada's, and then paying for healthcare reform out of general revenue, and then covering the cost by raising the income tax or the corporate tax or whatever other tax, well, Congress would have had the power to do that under Article 1 Section 8 Clause 1. But instead, instead of going to single payer, Congress decided to keep the private insurers at the center of the system. And to pay for it, in addition to the increased -- under an income tax and so forth, then to help pay for it through the play or pay individual mandate. Now, does that count as a tax under the taxing power of Article 1? Congress didn't call it a tax. I think probably they wanted to avoid the political fallout of saying that they raised taxes. I don't know what the courts are going to decide on this, but as Mr. Shapiro said, they pretty much focused on the other two, the Commerce Clause and the necessary and proper clause. So let's go to the Commerce Clause. And we'll start right off with the sharpest attack. Can Congress regulate the inaction of not buying health insurance? Can Congress say to us, play or pay? Well, the first point to observe is -- again, being no expert, but it seems to me this is an unplowed juridical fields. We don't have any direct authority one way or the other. The Supreme Court has never suggested that inactivity that a play or pay mandate is somehow foreclosed from general congressional authority over economic matters relating to interstate commerce. Second, and Mr. Shapiro is candid enough to say this, there's a strong argument that individual consumer's decisions not to buy health insurance now, but rather to wait until they get sick of hurt and then try to pay the bills directly then, those are economic decisions that in the aggregate, certainly do have a significant effect on interstate commerce. In fact, it seems to me that that fact is indisputable. Now, Mr. Shapiro and his colleagues raised the specter of government exercising unlimited power over individual choice. And some of his colleagues suggest that the division between acting and inaction is one good place to draw that line. But they would find a skeptic in none other than Justice Scalia, who in a different healthcare context, had this to say: "It would not make much sense to say that one may not kill one's self by walking into the sea, but may sit on the beach until submerged by the incoming tide; or that one may not intentionally lock oneself into a cold storage locker, but may refrain from coming indoors when the temperature drops below freezing. Even as a legislative matter," Scalia says, "in other words, the intelligent line does not fall between action and inaction." So the point is, what affects Congress is a difficult line to draw, and a deferential court would honor reasonable legislative judgments about when economic activity is or is not present. Finally, the necessary and proper clause. Here, we go back to the reasons for the play or pay mandate. Most importantly, besides the ethical reasons against freeloading that I was talking about, are the economic reasons, and they're easy to understand. Requiring insurers to accept all applicants, regardless of health condition, is a primary goal of the law. To put together a big enough pot of money to cover the newly insured and the people that, under the present flawed system, are denied coverage or cut off because of pre-existing conditions, well, you got to have everybody paying in. You've got to include in the people that want to freeload. You've got to include in the healthy, young people who think that they're invincible and will never get sick or will never be in a car crash. If you don't include them all in; if only the relatively unhealthy are in the insurance pool, then premiums go up, adverse selection takes over, more people drop out, premiums go up more, and it's the death spiral for cost control. That's just how the insurance industry, the insurance business works. So in other words, if moving the country closer toward universal health insurance is a legitimate national goal, and if we're going to keep a private health insurance industry in this country, then a democracy's legislative choice to help finance achievement of that goal through a play or pay mandate is a necessary and proper exercise of Congress's Article 1 power. Thanks. [ Applause ] First of all, I should have touched on this in my opening remarks, Professor Leflar said that buying insurance under the mandate or the minimal coverage provision, isn't mandatory. You have a choice. You can either buy it or pay the penalty. Well, I'm curious whether you also have a choice when a mugger comes up to you and says, your money or your life. We have a doctrine of unconstitutional conditions. We understand that at some point there's coercion. Here, there's government coercion. What if you don't want to do either of those things? And just because the government could raise income taxes or increase Medicare payroll taxes and fund all sorts of different programs that way, does not mean that it can also force you to buy health insurance or do something else. Each one of these is a different constitutional analysis. And it matters, because the text of the Constitution, because without the government getting its authority from the Constitution, then it gets it from the point of a gun, and we just have a majority rule. We have to address Professor Leflor's political point, a hugely unpopular bill from the very beginning, that caused Ted Kennedy's seat in Massachusetts to go to a Republican, that caused the rise of the Tea Party movement. We've had such a weird couple of years politically, ninety percent of which is tied to the unpopularity, which unpopularity is tied to people understanding -- they're not just disagreeing with the policy, but asking the question, where do you get the power to do this? There's a video of former, thankfully, Congressman Phil Hare of Illinois, who was asked this -- one of these guerrilla YouTube people. And he said, well, I don't care about the Constitution. I'm trying to take care of my constituents' interests, not understanding the contradiction between those two statements. Now, look. The threat to democracy, the threat to our system of government, and rule by consent of the governed, does not come from courts striking down legislative action. They come from any part of government not fulfilling its constitutional duties. This whole debate about judicial activism just means a decision I disagree with. Conservatives say X, Y and Z are judicial activist cases; liberals say A, B and C are. It doesn't mean anything. For a judge to notice that Congress is going beyond its constitutional power and do nothing about it, and do nothing, is judicial abdication. And if that's the position that Professor Leflar or any of the other advocates for ObamaCare take, then I guess they're against Marbury v. Madison and judicial review. What we're arguing is conflicting theories of the Constitution. I think we should all agree that judges should strike down pieces of legislation that are constitutional, either as going beyond the government's powers or violating individual rights. And I think those two are two sides of the same coin. Necessarily, when the government goes beyond its powers, it violates the retained rights. Necessarily, when rights are being violated, government is doing something it doesn't have the power to do. On the death spiral, freeloading, cost-shifting, these sorts of policy arguments. First of all, again, to the extent they're valid policy concerns, that's a separate question from the constitutional angle. Yes, of course, you cannot require insurers to cover people with pre-existing conditions and not have, force healthy people to get into that same pool. I mean, by doing that, you of course, eliminate the insurance industry. Our insurance industry with ObamaCare is no longer insurance; it's publicly regulated payment shifting and redistribution, and I don't know what you want to call it. Even before ObamaCare, our insurance industry was more or less a public utility, with guaranteed rates of returns for insurers. Their lobbyists, the big companies, they win either way. Don't worry or celebrate insurers or pharma getting into the neck. They're wining regardless of what happens. But just because it's essential to that particular scheme that Congress has designed to have the individual mandate doesn't make the individual mandate constitutional, or necessary and proper, or any one of these things. You could have -- this is where these broccoli or asparagus examples come up, right, or the buying Chevy example that I gave. Let's say that -- well, studies show that, scientific studies show, medical studies, that diet and exercise have a much greater effect on both healthcare outcomes and on taxpayer spending on healthcare than the ownership rate of insurance policies. So if anything, there's greater constitutional warrant to require people to buy, name your X healthy product, whether it be broccoli, asparagus, some other vegetable or some other thing -- or to join gyms. Now, there's a separate question about whether Congress can then actually physically take that broccoli and shove it down your throat, or force you to work out on that elliptical, chain you to it or something. That's a slightly different question. But requiring to purchase that, I don't see a difference between, and as I said, there's a greater warrant for that than for buying the insurance. Scalia's healthcare opinion, I thought Professor Leflar was going to talk about his concurrence in the medicinal marijuana case, which turns on activity and also turns on Scalia's drug war exception of the Constitution. Based on what Scalia's done since, he is not a swing vote here. I think he's firmly on the side of striking this down. And moreover, in the Koran case, that particular individual euthanasia case and whatnot, there's no government coercion there. It's a fundamental right case. It's analyzed completely differently. I guess I'll clear up one other thing about necessary and proper, because I got into a little bit too much legalese. When I was talking about those early wheat cases, Wickard, the New Deal cases, why it's important that they were all citing Chief Justice Marshall's McCulloch opinion rather than his Gibbons opinion is because the former is about necessary and proper while the latter is about the Commerce Clause. So if you look at how Chief Justice Marshall talks about for something to be necessary and proper, you don't evaluate whether something is more or less necessary. In that scion of limited government, Alexander Hamilton agrees, there has to be a line of justiciability. If you don't evaluate, well, that's necessary enough. That's not what you do. You see whether something comes within the letter and spirit of the Constitution, and precisely because there is no authorization for Congress to mandate things under the guise of regulating interstate commerce. McCulloch versus Maryland and all the necessary and proper cases going back to our founding, militate against upholding the individual mandate. Again, I can't emphasize enough. This is not about healthcare. There's lots of different markets that we can talk about, the food market, the housing market; you need food and housing before you need healthcare, that Congress can do. There's lots of different things that Congress can do in the national healthcare arena, but this goes beyond any existing power under modern doctrine. And if this mandate is struck down, no other law, no other opinion -- Wickard, Raich, nothing, needs to be struck down with it, because this is so singularly beyond anything that's happened. This so singularly eviscerates what remaining limits on federal power there are under modern constitutional law, that really, this is a turning point. And I think people recognize this, the overwhelming unpopularity. I think the latest poll -- just of the mandate, not ObamaCare altogether, but just of the mandate, is seventy percent people against it. That might help steal the spine of some judge or justice in the future. I can only hope. [ Applause ] We're going to go ahead and open it up for questions for anyone that's got a question for these guys. What you were talking about was very interesting, but the fact that we've got a table out here that's stacked heart attack high with pizza, with white flour, bad fat, salt, processed meat, says more about this issue than I think everything that you've said up here. Benjamin Franklin said, "An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," and that "a stitch in time saves nine." You add up the fact that we can be healthy. Green tea is significant. Apples, blueberries -- the simple things that are available to us right here at Wal-Mart, everywhere, is significant. We don't need healthcare; we need to be healthy. Thank you. If anyone-- And that's why I listen to my doctor rather than the government when I-- You can get seconds when it's over. So why doesn't the state of Arkansas -- I was a resident of Massachusetts for eight years prior to moving here. Why doesn't the state of Arkansas just do what Massachusetts did on the state level instead of asking the national government to mandate it, if you will? Well, it's a reasonable question. The question is, why doesn't Arkansas, why don't the different individual states do it on the state level and fix their healthcare systems on the state level rather than leaving it to the federal government to accomplish? And there are a couple of points that you got to make about that, because it cuts to the heart, really, of Mr. Shapiro's entire argument. This is a federalism question, is this a matter for Congress to take care of, for Congress to address as a national issue, or is it something that is properly and necessarily left to the states? Good question. My answer to it would be that healthcare, the healthcare problems that we have are irretrievably and inevitably national in scope, and that a single state can't fix the problems in and of itself, particularly states that have less resources, Arkansas being among those. We are left in Arkansas, as I pointed out, with a terrible situation of more than half a million people without basic health insurance. They cannot get it. And that foists burdens on all the rest of us, the taxpayers and the people who are fortunate enough to have it. And these are issues that single state-by-state solutions, although they can serve as guideposts for other states -- Massachusetts has done so; Utah, Hawaii has done so -- they won't take care of the whole national problem. And so, I think that part of what for example, the Commerce Clause is all about, is saying to Congress, if it's a national problem, then you may address it under interstate commerce, and you have the means, and they're generous means, through the necessary and proper clause, to accomplish that in some kind of national light, in some kind of reasonable way. Now, as Mr. Shapiro said, there are many possible approaches to addressing those problems. Congress has chosen one among those approaches. As long as there's a rational basis for proving that it's democratic choice of the people that we elected, then the courts should not strike it down. Well, this is why we're against RomneyCare and we don't hesitate in tweaking our friends at the Heritage Foundation for inventing that, and it's probably why Mitt Romney's going to have trouble in the Republican primaries the longer that this stays a salient issue. But states -- as Romney said, and continues to say to try to kind of massage his points -- states should have and do have flexibility to resolve their own policy issues as they like. What's more local -- not even state, but local, than somebody going into their doctor to have a check-up or somebody having a heart attack. That's very different than regulating an industry. Just like states are the ones that criminalize murder and robbery and rape and these sorts of things; not the federal government. Although the federal government has overfederalized a lot of different laws. For example, the federal carjacking law. It wasn't that carjacking was legal until Congress passed a law against it. It was always illegal to use weapons to steal somebody's car and rough them -- not like any state allowed that. But just like in the Morrison case in 2000, which struck down the Violence Against Women Act, the theory there was that when women are threatened or attacked, assaulted, that affects their productivity which affects interstate commerce. And the Court said, well, no, that's not too attenuated from economic activity. So similarly here, this is properly under the purview of the states, and then you got the issue of whether one of your individual rights is to refrain from having -- that's a separate type of constitutional argument. But states, yeah, absolutely, should have flexibility in this area as in many others that they enjoy about how to regulate different aspects of policy. Just because they don't doesn't mean that Congress says, oh, well, we see that these states are failing to do anything, and therefore we get that power. It's not the way the Constitution works. We've actually got the room for one minute, so we're going to have to wrap it up. But I encourage you all to read-- Is somebody else coming into the room? We've got a class here in just about ten minutes. But I encourage you all to read the recent Florida opinion, and let us know on our Facebook page whether or not Professor Leflor's interpretation of the Commerce Clause is true and correct. I think that the Florida judge had his own theories on that, as did possibly the founders of this great nation. So thank you, all. Thank you to the University of Arkansas School of Law, and to our guests. [ Applause ]

Details

During the presidency of Barack Obama, who campaigned heavily on accomplishing health care reform, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was enacted in March 2010.

In the next administration, President Trump said the healthcare system should work based on free market principles. He endorsed a seven-point plan for healthcare reform:

- repeal Obamacare

- reduce barriers to the interstate sale of health insurance

- institute a full tax deduction for insurance premium payments for individuals

- make Health Saving Accounts inheritable

- require price transparency

- block-grant Medicaid to the states

- allow for more overseas drug providers through lowered regulatory barriers

He also suggested that enforcing immigration laws could reduce healthcare costs.[1]

The Trump administration made efforts to repeal the ACA and replace it with a different healthcare policy (known as a "repeal and replace" approach), but it never succeeded in doing so through Congress.[2] Next, the administration joined a lawsuit seeking to overturn the ACA, and the Supreme Court agreed at the beginning of March 2020 that it would hear the case. Under normal scheduling, the case would be heard in the fall of 2020 and decided in the spring of 2021. However, as the Supreme Court subsequently went on hiatus in response to the coronavirus pandemic, it is unclear when the case will be heard.[3]

Cost debate

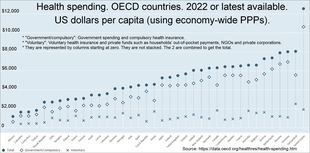

U.S. healthcare costs were approximately $3.2 trillion or nearly $10,000 per person on average in 2015. Major categories of expense include hospital care (32%), physician and clinical services (20%), and prescription drugs (10%).[7] U.S. costs in 2016 were substantially higher than other OECD countries, at 17.2% GDP versus 12.4% GDP for the next most expensive country (Switzerland).[8] For scale, a 5% GDP difference represents about $1 trillion or $3,000 per person. Some of the many reasons cited for the cost differential with other countries include: Higher administrative costs of a private system with multiple payment processes; higher costs for the same products and services; more expensive volume/mix of services with higher usage of more expensive specialists; aggressive treatment of very sick elderly versus palliative care; less use of government intervention in pricing; and higher income levels driving greater demand for healthcare.[9][10][11] Healthcare costs are a fundamental driver of health insurance costs, which leads to coverage affordability challenges for millions of families. There is ongoing debate whether the current law (ACA/Obamacare) and the Republican alternatives (AHCA and BCRA) do enough to address the cost challenge.[12]

In 2009, the U.S. had the highest health care costs relative to the size of the economy (GDP) in the world, with an estimated 50.2 million citizens (approximately 16% of the September 2011 estimated population of 312 million) without insurance coverage. Some critics of reform counter that almost four out of ten of these uninsured come from a household with over $50,000 income per year, and thus might be uninsured voluntarily, or opting to pay for health care services on a "pay-as-you-go" basis.[13] Further, an estimated 77 million Baby Boomers are reaching retirement age, which combined with significant annual increases in healthcare costs per person will place enormous budgetary strain on U.S. state and federal governments.[14] Maintaining the long-term fiscal health of the U.S. federal government is significantly dependent on healthcare costs being controlled.[15]

Quality of care

There is significant debate regarding the quality of the U.S. healthcare system relative to those of other countries. Physicians for a National Health Program, a political advocacy group, has claimed that a free market solution to healthcare provides a lower quality of care, with higher mortality rates, than publicly funded systems.[16] The quality of health maintenance organizations and managed care have also been criticized by this same group.[17]

According to a 2015 report from The Commonwealth Fund, although the United States pays almost twice as much per capita towards healthcare as other wealthy countries with universal healthcare, patient outcomes are poorer. The United States has the lowest life expectancy overall and the infant mortality rate is the highest and in some cases twice as high when compared with other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.[18] Also highlighted in this report is data that shows that although Americans have one of the lowest percentages of daily smokers, they have the highest mortality rate for heart disease, a significantly higher obesity rate and more amputations due to diabetes. Other health related issues highlighted were that Americans over the age of 65 have a higher percentage of the population with two or more chronic conditions and the lowest percentage of that age group living.[citation needed]

According to a 2000 study of the World Health Organization (WHO), publicly funded systems of industrial nations spend less on healthcare, both as a percentage of their GDP and per capita, and enjoy superior population-based health care outcomes.[19] However, conservative commentator David Gratzer and the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, have both criticized the WHO's comparison method for being biased; the WHO study marked down countries for having private or fee-paying health treatment and rated countries by comparison to their expected healthcare performance, rather than objectively comparing quality of care.[20][21]

Some medical researchers say that patient satisfaction surveys are a poor way to evaluate medical care. Researchers at the RAND Corporation and the Department of Veterans Affairs asked 236 elderly patients in two different managed care plans to rate their care, then examined care in medical records, as reported in Annals of Internal Medicine. There was no correlation. "Patient ratings of health care are easy to obtain and report, but do not accurately measure the technical quality of medical care," said John T. Chang, UCLA, lead author.[22][23][24]

There are health losses from insufficient health insurance. A 2009 Harvard study published in the American Journal of Public Health found more than 44,800 excess deaths annually in the United States due to Americans lacking health insurance.[25][26] More broadly, estimates of the total number of people in the United States, whether insured or uninsured, who die because of lack of medical care were estimated in a 1997 analysis to be nearly 100,000 per year.[27]

A 2007 article from The BMJ by Steffie Woolhandler and David Himmelstein strongly argued that the United States' healthcare model delivered inferior care at inflated prices, and further stated: "The poor performance of US health care is directly attributable to reliance on market mechanisms and for-profit firms and should warn other nations from this path."[28]

Cost and efficiency

The United States spends a higher proportion of its GDP on healthcare (19%) than any other country in the world, except for East Timor (Timor-Leste).[29] The number of employers who offer health insurance is declining. Costs for employer-paid health insurance are rising rapidly: since 2001, premiums for family coverage have increased 78%, while wages have risen 19% and prices have risen 17%, according to a 2007 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation.[30]

Private insurance in the US varies greatly in its coverage; one study by the Commonwealth Fund published in Health Affairs estimated that 16 million U.S. adults were underinsured in 2003. The underinsured were significantly more likely than those with adequate insurance to forgo healthcare, report financial stress because of medical bills, and experience coverage gaps for such items as prescription drugs. The study found that underinsurance disproportionately affects those with lower incomes – 73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.[31]

However, a study published by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2008 found that the typical large employer Preferred provider organization (PPO) plan in 2007 was more generous than either Medicare or the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program Standard Option.[32] One indicator of the consequences of Americans' inconsistent health care coverage is a study in Health Affairs that concluded that half of personal bankruptcies involved medical bills,[33] although other sources dispute this.[34]

Proponents of healthcare reforms involving expansion of government involvement to achieve universal healthcare argue that the need to provide profits to investors in a predominantly free market health system, and the additional administrative spending, tends to drive up costs, leading to more expensive provision.[16]

According to economist and former US Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, only a "big, national, public option" can force insurance companies to cooperate, share information, and reduce costs. Scattered, localized, "insurance cooperatives" are too small to do that and are "designed to fail" by the moneyed forces opposing Democratic health care reform.[35][36]

Impact on U.S. economic productivity

On March 1, 2010, billionaire Warren Buffett said that the high costs paid by U.S. companies for their employees' healthcare put them at a competitive disadvantage. He compared the roughly 17% of GDP spent by the U.S. on healthcare with the 9% of GDP spent by much of the rest of the world, noted that the U.S. has fewer doctors and nurses per person, and said, "that kind of a cost, compared with the rest of the world, is like a tapeworm eating at our economic body."[37]

Allegations of waste

In December 2011 the outgoing Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Donald Berwick, asserted that 20% to 30% of healthcare spending is waste. He listed five causes for the waste: (1) overtreatment of patients, (2) the failure to coordinate care, (3) the administrative complexity of the system, (4) burdensome rules and (5) fraud.[38]

Ideas for reform

During a June 2009 speech, President Barack Obama outlined his strategy for reform. He mentioned electronic record-keeping, preventing expensive conditions, reducing obesity, refocusing doctor incentives from quantity of care to quality, bundling payments for treatment of conditions rather than specific services, better identifying and communicating the most cost-effective treatments, and reducing defensive medicine.[39]

President Obama further described his plan in a September 2009 speech to a joint session of Congress. His plan mentions: deficit neutrality; not allowing insurance companies to discriminate based on pre-existing conditions; capping out of pocket expenses; creation of an insurance exchange for individuals and small businesses; tax credits for individuals and small companies; independent commissions to identify fraud, waste and abuse; and malpractice reform projects, among other topics.[40][41]

OMB Director Peter Orszag described aspects of the Obama administration's strategy during an interview in November 2009: "In order to help contain [Medicare and Medicaid] cost growth over the long term, we need a new healthcare system that has digitized information... in which that information is used to assess what's working and what's not more intelligently, and in which we're paying for quality rather than quantity while also encouraging prevention and wellness." He also argued for bundling payments and accountable care organizations, which reward doctors for teamwork and patient outcomes.[15]

Mayo Clinic President and CEO Denis Cortese has advocated an overall strategy to guide reform efforts. He argued that the U.S. has an opportunity to redesign its healthcare system and that there is a wide consensus that reform is necessary. He articulated four "pillars" of such a strategy:[42]

- Focus on value, which he defined as the ratio of quality of service provided relative to cost;

- Pay for and align incentives with value;

- Cover everyone;

- Establish mechanisms for improving the healthcare service delivery system over the long-term, which is the primary means through which value would be improved.

Writing in The New Yorker, surgeon Atul Gawande further distinguished between the delivery system, which refers to how medical services are provided to patients, and the payment system, which refers to how payments for services are processed. He argued that reform of the delivery system is critical to getting costs under control, but that payment system reform (e.g., whether the government or private insurers process payments) is considerably less important yet gathers a disproportionate share of attention. Gawande argued that dramatic improvements and savings in the delivery system will take "at least a decade." He recommended changes that address the overutilization of healthcare; the refocusing of incentives on value rather than profits; and comparative analysis of the cost of treatment across various healthcare providers to identify best practices. He argued this would be an iterative, empirical process and should be administered by a "national institute for healthcare delivery" to analyze and communicate improvement opportunities.[43]

Use of comparative effectiveness research

Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. Writing in the New York Times, David Leonhardt described how the cost of treating the most common form of early-stage, slow-growing prostate cancer ranges from an average of $2,400 (watchful waiting to see if the condition deteriorates) to as high as $100,000 (radiation beam therapy):[44]

According to economist Peter A. Diamond and research cited by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.[45]

Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. OMB Director Peter Orszag stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."[43]

Reform of doctor's incentives

Critics have argued that the healthcare system has several incentives that drive costly behavior. Two of these include:[46]

- Doctors are typically paid for services provided rather than with a salary. This payment system (which is often referred to as "fee-for-service") provides a financial incentive to increase the costs of treatment provided.

- Patients that are fully insured have no financial incentive to minimize the cost when choosing from among alternatives. The overall effect is to increase insurance premiums for all.

Insurance reforms

The debate has involved certain insurance industry practices such as the placing of caps on coverage, the high level of co-pays even for essential services such as preventative procedures, the refusal of many insurers to cover pre-existing conditions or adding premium loading for these conditions, and practices which some people regard as egregious such as the additional loading of premiums for women, the regarding of having previously been assaulted by a partner as having a pre-existing condition, and even the cancellation of insurance policies on very flimsy grounds when a claimant who had paid in many premiums presents with a potentially expensive medical condition.[citation needed]

Various legislative proposals under serious consideration propose fining larger employers who do not provide a minimum standard of healthcare insurance and mandating that people purchase private healthcare insurance. This is the first time that the Federal government has mandated people to buy insurance, although nearly all states in the union currently mandate the purchase of auto insurance. The legislation also taxes certain very high payout insurance policies (so-called "Cadillac policies") to help finance subsidies for poorer citizens. These will be offered on a sliding scale to people earning less than four times the federal poverty level to enable them to buy health insurance if they are not otherwise covered by their employer.[citation needed]

The issue of concentration of power by the insurance industry has also been a focus of debate as in many states very few large insurers dominate the market. Legislation which would provide a choice of a not-for-profit insurer modeled on Medicare but funded by insurance premiums has been a contentious issue. Much debate surrounded Medicare Advantage and the profits of insurers selling it.[47]

Certain proposals include a choice of a not-for-profit insurer modeled on Medicare (sometimes called the "government option"). Democratic legislators have largely supported the proposed reform efforts, while Republicans have criticized the government option or expanded regulation of healthcare.

The GAO reported in 2002 (using 2000 data) that: "The median number of licensed carriers in the small group market per state was 28, with a range from 4 in Hawaii to 77 in Indiana. The median market share of the largest carrier was about 33 percent, with a range from about 14 percent in Texas to about 89 percent in North Dakota."[48]

The GAO reported in 2008 (using 2007 data for the most part) that: "The median number of licensed carriers in the small group market per state was 27. The median market share of the largest carrier in the small group market was about 47%, with a range from about 21% in Arizona to about 96% in Alabama. In 31 of the 39 states supplying market share information, the top carrier had a market share of a third or more. The five largest carriers in the small group market, when combined, represented three quarters or more of the market in 34 of the 39 states supplying this information, and they represented 90% or more in 23 of these states....the median market share of all the BCBS carriers in 38 states reporting this information in 2008 was about 51%, compared to the 44% reported in 2005 and the 34% reported in 2002 for the 34 states supplying information in each of these years."[49]

Tax reform

The Congressional Budget Office has also described how the tax treatment of insurance premiums may affect behavior:[50]

One factor perpetuating inefficiencies in health care is a lack of clarity regarding the cost of health insurance and who bears that cost, especially employment-based health insurance. Employers' payments for employment-based health insurance and nearly all payments by employees for that insurance are excluded from individual income and payroll taxes. Although both theory and evidence suggest that workers ultimately finance their employment-based insurance through lower take-home pay, the cost is not evident to many workers.... If transparency increases and workers see how much their income is being reduced for employers' contributions and what those contributions are paying for, there might be a broader change in cost-consciousness that shifts demand.

In November 2009, The Economist estimated that taxing employer-provided health insurance (which is presently exempt from tax) would add $215 billion per year to federal tax revenue during the 2013–2014 periods.[51] Peter Singer wrote in The New York Times that the current exclusion of insurance premiums from compensation represents a $200 billion subsidy for the private insurance industry and that it would likely not exist without it.[52] In other words, taxpayers might be more inclined to change behavior or the system itself if they were paying $200 billion more in taxes each year related to health insurance. To put this amount in perspective, the federal government collected $1,146 billion in income taxes in 2008,[53] so $200 billion represents a 17.5% increase in the effective tax rate.

Independent advisory panels

President Obama has proposed an "Independent Medicare Advisory Panel" (IMAC) to make recommendations on Medicare reimbursement policy and other reforms. Comparative effectiveness research would be one of many tools used by the IMAC. The IMAC concept was endorsed in a letter from several prominent healthcare policy experts, as summarized by OMB Director Peter Orszag:[54]

Their support of the IMAC proposal underscores what most serious health analysts have recognized for some time: that moving toward a health system emphasizing quality rather than quantity will require continual effort, and that a key objective of legislation should be to put in place structures (like the IMAC) that facilitate such change over time. And ultimately, without a structure in place to help contain costs over the long term as the health market evolves, nothing else we do in fiscal policy will matter much, because eventually rising health care costs will overwhelm the federal budget.

Both Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. Denis Cortese and surgeon/author Atul Gawande have argued that such panel(s) will be critical to reform of the delivery system and improving value. Washington Post columnist David Ignatius has also recommended that President Obama engage someone like Cortese to have a more active role in driving reform efforts.[55]

Lowering obesity

Preventing obesity and overweight conditions presents a significant opportunity to reduce costs. The Centers for Disease Control reported that approximately 9% of healthcare costs in 1998 were attributable to overweight and obesity, or as much as $93 billion in 2002 dollars. Nearly half of these costs were paid for by the government via Medicare or Medicaid.[56] However, by 2008 the CDC estimated these costs had nearly doubled to $147 billion.[57] The CDC identified a series of expensive conditions more likely to occur due to obesity.[58] The CDC released a series of strategies to prevent obesity and overweight, including: making healthy foods and beverages more available; supporting healthy food choices; encouraging kids to be more active; and creating safe communities to support physical activity.[59][60] An estimated 26% of U.S. adults in 2007 were obese, versus 24% in 2005. State obesity rates ranged from 18% to 30%. Obesity rates were roughly equal among men and women.[61] Some have proposed a so-called "fat tax" to provide incentives for healthier behavior, either by levying the tax on products (such as soft drinks) that are thought to contribute to obesity,[62] or to individuals based on body measures, as is done in Japan.[63]

Rationing of care

Healthcare rationing may refer to the restriction of medical care service delivery based on any number of objective or subjective criteria. Republican Newt Gingrich argued that the reform plans supported by President Obama expand the control of government over healthcare decisions, which he referred to as a type of healthcare rationing.[64] President Obama has argued that U.S. healthcare is already rationed, based on income, type of employment, and medical pre-existing conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured. He argued that millions of Americans are denied coverage or face higher premiums as a result of medical pre-existing conditions.[65]

Peter Singer wrote in the New York Times in July 2009 that healthcare is rationed in the United States and argued for improved rationing processes:[66]

Health care is a scarce resource, and all scarce resources are rationed in one way or another. In the United States, most healthcare is privately financed, and so most rationing is by price: you get what you, or your employer, can afford to insure you for...Rationing healthcare means getting value for the billions we are spending by setting limits on which treatments should be paid for from the public purse. If we ration we won't be writing blank checks to pharmaceutical companies for their patented drugs, nor paying for whatever procedures doctors choose to recommend. When public funds subsidize healthcare or provide it directly, it is crazy not to try to get value for money. The debate over healthcare reform in the United States should start from the premise that some form of healthcare rationing is both inescapable and desirable. Then we can ask, What is the best way to do it?"

According to PolitiFact, private health insurance companies already ration healthcare by income, by denying health insurance to those with pre-existing conditions and by caps on health insurance payments. Rationing exists now, and will continue to exist with or without healthcare reform.[67] David Leonhardt also wrote in the New York Times in June 2009 that rationing is a part of economic reality: "The choice isn't between rationing and not rationing. It's between rationing well and rationing badly. Given that the United States devotes far more of its economy to healthcare than other rich countries, and gets worse results by many measures, it's hard to argue that we are now rationing very rationally."[68]