Electrophilic aromatic substitution (SEAr) is an organic reaction in which an atom that is attached to an aromatic system (usually hydrogen) is replaced by an electrophile. Some of the most important electrophilic aromatic substitutions are aromatic nitration, aromatic halogenation, aromatic sulfonation, alkylation Friedel–Crafts reaction and acylation Friedel–Crafts reaction.[1]

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/3Views:352 34240 49380 178

-

Electrophilic aromatic substitution | Aromatic Compounds | Organic chemistry | Khan Academy

-

Electrophillic Aromatic Substitution

-

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution - EAS Introduction by Leah4sci

Transcription

We've already talked about how a benzene ring is very-- let me draw a better looking benzene ring than that-- that a benzene ring is very stable, because it's aromatic. That these electrons in these pi orbitals that form these double bonds, they're actually just not in this double bond, they can keep swapping. This one can go here. This one can go there. That one can go there. Actually, they don't go back and forth. They actually just completely go around the entire ring. And when a molecule is aromatic, it stabilizes it. But we've seen examples of aromatic, or actually, in particular, we've seen examples of benzene rings that have other things bumping off of them, whether they're halides or whether they're OH groups, and what we want to do in this video is think about how that might happen, how do things get added on to a benzene ring. We're going to learn about electrophilic aromatic substitution. Let me write that down. Electrophilic aromatic substitution. And you might say, well, Sal, you just said you're adding things to the ring. But the reality is that there's six hydrogens here. There's one hydrogen, two hydrogens, three hydrogens, four hydrogens, five hydrogens and six hydrogens. They're always there. If you don't draw them, they are implicitly there. So what we're actually doing, when you add a chlorine or a bromine or an OH group, it's actually replacing one of these hydrogens. That's why it is substitution. It's aromatic, because we're dealing with a benzene ring. We're dealing with an aromatic molecule, and we're going to see that we need a really strong electrophile in order to do this. Let's think about this how this will happen. Before I do that, let me just copy and paste this, because I don't want to have to redraw this. Let me just copy it, just like that. So let's say we have a really strong electrophile. And I'll give you particular cases in the next few videos, so you can better visualize what a really strong electrophile is. But just from the word itself, electrophile, you could imagine it's something that loves electrons. It wants electrons really, really, really, really, really badly. And usually, it has a positive charge. So it wants electrons badly. And actually, let me make it very clear. Instead of saying it wants electrons badly, because when you're talking about electrophiles or nucleophiles, you're actually talking about how good something is reacting, you're not actually talking about the actual energies involved. Let me put it a different way: good at getting electrons. Really, really, really, really, really good at getting electrons. So what would happen? We already said this is already pretty stable. These guys, these electrons, these pi electrons can circulate all around. If it bumps just in the right way to something that's really good at getting electrons, what might happen-- let's say we have this electron right here. The way we've drawn it, it's on this carbon right here. Obviously, the carbon is just at the intersection. I never drew the carbon. But if this electrophile, which is really good at getting electrons, bumps in just the right way, this electron can go to that electrophile. And then it would be left with-- so let me copy and paste our original molecule. So then what would we be left with? So we no longer have this bond right here. It has now been bonded to the electrophile. Let me make it clear. We had this electron right here. That electron is still on this carbon right over here at this intersection, but the other end of it, the other electron, has now been given to the electrophile, the thing that's good at getting them. So the other side has been given to this electrophile. This electrophile now gained an electron. So it had a positive charge, now it will be neutral. And once again, I'll show you a particular, or several particular cases of this in the next few videos. Let me just make it clear. So this bond, you could now view it as being this bond. Now, this carbon right over here, this lost an electron. So if it lost an electron, it will now have a positive charge. Now, this is hard to do to a resonance-stabilized molecule, to a benzene ring. So that, once again, and I said, and I'm being a little bit repetitive, this has to be a very good electrophile to do it. But once this is there, this is a actually relatively stable carbocation. The reason why it is, it's only a secondary carbocation, but it's actually a resonance-stabilized carbocation because this electron right can be given to that. If this electron goes there, then it would look like this. Let me redraw it. I'll draw the resonance structures quickly. You have your hydrogen. You have your electrophile. That's not an electrophile anymore, but you have that E that's now been added. You have that hydrogen. You have a double bond here. Let me draw a little bit neater. You have this hydrogen. You have this hydrogen, this hydrogen and this hydrogen. What I said is, this is stabilized. So an electron here can actually jump over here. So if this electron jumps over here, the double bond is now over there If that goes over there like that, the double bond is now over here. Now this guy lost his electron and it would have a positive charge. And then that is resonance stabilized. It can either go back to this guy, or this electron over here can jump over there. Let me redraw the whole thing over again. Let me draw all the hydrogens. This right here, you have the E and the hydrogen. You have a hydrogen here, hydrogen here, hydrogen here, hydrogen here. And normally you don't worry about the hydrogens, but one of the hydrogens is going to be nabbed later on in this mechanism, so I want to draw all the hydrogens just so you know that they are there. But as I said, this is resonance stabilized. If this electron right here jumps over there, then this double bond is now this double bond. And now this guy over here lost an electron, so it would have a positive charge. And again, once you had this double bond up here, this double bond up there is that double bond. So we can go back and forth between these. The electrons are just swishing around the ring. So it's not going to be maybe as great as the situation that we had when we had a nice benzene ring that was completely aromatic. The electrons can just go around the p-orbitals, around and around the ring, stabilize the structure, but this is still a relatively stable carbocation, because the electrons can move around. You can kind of view it as a positive charge that gets dispersed between this carbon, this carbon, and that carbon over there. As I said, it's still not a great situation. The molecule wants to go back to being aromatic, wants to go to that really stable state. And the way it can go back to that really stable state is somehow an electron can be added to this thing. And the way that an electron can be added to this thing is, if we have some base flying around, and that base nabs this proton, this proton right here that's on the same carbon as where the electrophile is attached. So if this base nabs a proton, so it just nabs the hydrogen nucleus, then that electron that the hydrogen had, that electron-- let me do that in a different color. That electron that the hydrogen had right over there could then be returned to this carbon up there. And maybe that makes it a little confusing when I cross lines. It can be returned to that carbon right there. So what would it look like after that? After that it would look like this. Let me draw my-- so if that happened, and we drew it in yellow, we have our six-carbon ring. Let me draw all the hydrogens. What did I do that in? It likes like a slightly green color I did that in. So I have all the hydrogens on that ring. Now, I have to be careful. This hydrogen right there, just the nucleus of it, got nabbed by this base. So that hydrogen has now been nabbed by the base. This electron right here has now been given to this hydrogen. So that electron has now been given to this hydrogen, and then the other electron in the pair is still with the base. So now this is the conjugate acid of the base. It has gained a proton. And on this carbon, right here, we just have what was the electrophile. And I'll do the same colors, just to make it clear. What was the electrophile right over there, this bond is this bond. And then finally, we had-- and I'll color code it here just to make it clear. We had this double bond here, which is this double bond right over here. We had this double bond. We had this double bond, which is that double bond there. And then this electron gets returned to this top carbon right here. So that electron-- let me make it very, very clear. So the bond and that electron are returned to that top carbon. So that we have the bond and that electron returned to that top carbon. That top carbon is now going to be neutral. And once again, we are resonance stabilized. One thing I forgot, just to make the charge stabilized, maybe this base had a negative charge to begin with. It didn't have to. But if this base did have a negative charge to begin with, it now gave an electron to the hydrogen, so it is now neutral. And this should make sense because before we had a plus charge and a negative charge, and then when everything reacted, everything is neutral again. The total net charge is zero. But this is the electrophilic aromatic substitution. We substituted one of the hydrogens. We substituted this hydrogen right here with this electrophile, or what was previously an electrophile, but then once it got an electron, it's just kind of a group that is now on the benzene ring. And by going through this little convoluted process, we finally got to another aromatic molecule that now has this E group on it. In the next video, I'll show you this with particular examples of electrophiles and bases.

Illustrative reactions

The most widely practised example of this reaction is the ethylation of benzene.

Approximately 24,700,000 tons were produced in 1999.[2] (After dehydrogenation and polymerization, the commodity plastic polystyrene is produced.) In this process, acids are used as catalyst to generate the incipient carbocation. Many other electrophilic reactions of benzene are conducted, although on a much smaller scale; they are valuable routes to key intermediates. The nitration of benzene is achieved via the action of the nitronium ion as the electrophile. The sulfonation with fuming sulfuric acid gives benzenesulfonic acid. Aromatic halogenation with bromine, chlorine, or iodine gives the corresponding aryl halides. This reaction is typically catalyzed by the corresponding iron or aluminum trihalide.

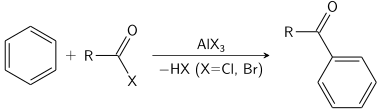

The Friedel–Crafts reaction can be performed either as an acylation or as an alkylation. Often, aluminium trichloride is used, but almost any strong Lewis acid can be applied. For the acylation reaction a stoichiometric amount of aluminum trichloride is required.

Reaction mechanism

The overall reaction mechanism, denoted by the Hughes–Ingold mechanistic symbol SEAr,[3] begins with the aromatic ring attacking the electrophile E+ (2a). This step leads to the formation of a positively charged and delocalized cyclohexadienyl cation, also known as an arenium ion, Wheland intermediate, or arene σ-complex (2b). Many examples of this carbocation have been characterized, but under normal operating conditions these highly acidic species will donate the proton attached to the sp3 carbon to the solvent (or any other weak base) to reestablish aromaticity. The net result is the replacement of H by E in the aryl ring (3).

Occasionally, other electrofuges (groups that can leave without their electron pair) beside H+ will depart to reestablish aromaticity; these species include silyl groups (as SiR3+), the carboxy group (as CO2 + H+), the iodo group (as I+), and tertiary alkyl groups like t-butyl (as R+). The capacity of these types of substituents to leave is sometimes exploited synthetically, particularly the case of replacement of silyl by another functional group (ipso attack). However, the loss of groups like iodo or alkyl is more often an undesired side reaction.

Effect of substituent groups

Both the regioselectivity—the diverse arene substitution patterns—and the speed of an electrophilic aromatic substitution are affected by the substituents already attached to the benzene ring. In terms of regioselectivity, some groups promote substitution at the ortho or para positions, whereas other groups favor substitution at the meta position. These groups are called either ortho–para directing or meta directing, respectively. In addition, some groups will increase the rate of reaction (activating) while others will decrease the rate (deactivating). While the patterns of regioselectivity can be explained with resonance structures, the influence on kinetics can be explained by both resonance structures and the inductive effect.

Reaction rate

Substituents can generally be divided into two classes regarding electrophilic substitution: activating and deactivating towards the aromatic ring. Activating substituents or activating groups stabilize the cationic intermediate formed during the substitution by donating electrons into the ring system, by either inductive effect or resonance effects. Examples of activated aromatic rings are toluene, aniline and phenol.

The extra electron density delivered into the ring by the substituent is not distributed evenly over the entire ring but is concentrated on atoms 2, 4 and 6, so activating substituents are also ortho/para directors (see below).

On the other hand, deactivating substituents destabilize the intermediate cation and thus decrease the reaction rate by either inductive or resonance effects. They do so by withdrawing electron density from the aromatic ring. The deactivation of the aromatic system means that generally harsher conditions are required to drive the reaction to completion. An example of this is the nitration of toluene during the production of trinitrotoluene (TNT). While the first nitration, on the activated toluene ring, can be done at room temperature and with dilute acid, the second one, on the deactivated nitrotoluene ring, already needs prolonged heating and more concentrated acid, and the third one, on very strongly deactivated dinitrotoluene, has to be done in boiling concentrated sulfuric acid. Groups that are electron-withdrawing by resonance decrease the electron density especially at positions 2, 4 and 6, leaving positions 3 and 5 as the ones with comparably higher reactivity, so these types of groups are meta directors (see below). Halogens are electronegative, so they are deactivating by induction, but they have lone pairs, so they are resonance donors and therefore ortho/para directors.

Ortho/para directors

Groups with unshared pairs of electrons, such as the amino group of aniline, are strongly activating (some time deactivating also in case of halides) and ortho/para-directing by resonance. Such activating groups donate those unshared electrons to the pi system, creating a negative charge on the ortho and para positions. These positions are thus the most reactive towards an electron-poor electrophile. This increased reactivity might be offset by steric hindrance between activating group and electrophile but on the other hand there are two ortho positions for reaction but only one para position. Hence the final outcome of the electrophilic aromatic substitution is difficult to predict, and it is usually only established by doing the reaction and observing the ratio of ortho versus para substitution.

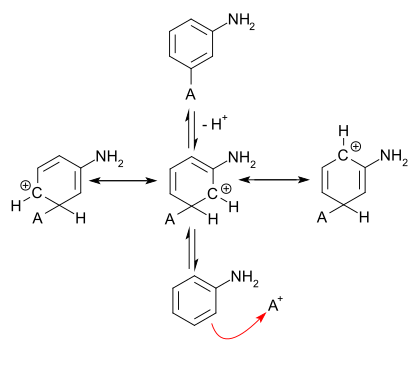

In addition to the increased nucleophilic nature of the original ring, when the electrophile attacks the ortho and para positions of aniline, the nitrogen atom can donate electron density to the pi system (forming an iminium ion), giving four resonance structures (as opposed to three in the basic reaction). This substantially enhances the stability of the cationic intermediate.

When the electrophile attacks the meta position, the nitrogen atom cannot donate electron density to the pi system, giving only three resonance contributors. This reasoning is consistent with low yields of meta-substituted product.

Other substituents, such as the alkyl and aryl substituents, may also donate electron density to the pi system; however, since they lack an available unshared pair of electrons, their ability to do this is rather limited. Thus, they only weakly activate the ring and do not strongly disfavor the meta position.

Directed ortho metalation is a special type of EAS with special ortho directors.

Meta directors

Non-halogen groups with atoms that are more electronegative than carbon, such as a carboxylic acid group (-CO2H), withdraw substantial electron density from the pi system. These groups are strongly deactivating groups. Additionally, since the substituted carbon is already electron-poor, any structure having a resonance contributor in which there is a positive charge on the carbon bearing the electron-withdrawing group (i.e., ortho or para attack) is less stable than the others. Therefore, these electron-withdrawing groups are meta directing because this is the position that does not have as much destabilization.

The reaction is also much slower (a relative reaction rate of 6×10−8 compared to benzene) because the ring is less nucleophilic.

Reaction on pyridine

Compared to benzene, the rate of electrophilic substitution on pyridine is much slower, due to the higher electronegativity of the nitrogen atom. Additionally, the nitrogen in pyridine easily gets a positive charge either by protonation (from nitration or sulfonation) or Lewis acids (such as AlCl3) used to catalyze the reaction. This makes the reaction even slower by having adjacent formal charges on carbon and nitrogen or 2 formal charges on a localised atom. Doing an electrophilic substitution directly in pyridine is nearly impossible.

In order to do the reaction, they can be made by 2 possible reactions, which are both indirect.

One possible way to do a substitution on pyridine is nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Even with no catalysts, the nitrogen atom, being electronegative, can hold the negative charge by itself. Another way is to do an oxidation before the electrophilic substitution. This makes pyridine N-oxide, which due to the negative oxygen atom, makes the reaction faster than pyridine, and even benzene. The oxide then can be reduced to the substituted pyridine.

Ipso attack

The attachment of an entering group to a position in an aromatic compound already carrying a substituent group (other than hydrogen). The entering group may displace that substituent group but may also itself be expelled or migrate to another position in a subsequent step. The term 'ipso-substitution' is not used, since it is synonymous with substitution.[4] A classic example is the reaction of salicylic acid with a mixture of nitric and sulfuric acid to form picric acid. The nitration of the 2 position involves the loss of CO2 as the leaving group. Desulfonation in which a sulfonyl group is substituted by a proton is a common example. See also Hayashi rearrangement. In aromatics substituted by silicon, the silicon reacts by ipso substitution.

Five membered heterocycles

Compared to benzene, furans, thiophenes, and pyrroles are more susceptible to electrophilic attack. These compounds all contain an atom with an unshared pair of electrons (oxygen, sulfur, or nitrogen) as a member of the aromatic ring, which substantially stabilizes the cationic intermediate. Examples of electrophilic substitutions to pyrrole are the Pictet–Spengler reaction and the Bischler–Napieralski reaction.

Asymmetric electrophilic aromatic substitution

Electrophilic aromatic substitutions with prochiral carbon electrophiles have been adapted for asymmetric synthesis by switching to chiral Lewis acid catalysts especially in Friedel–Crafts type reactions. An early example concerns the addition of chloral to phenols catalyzed by aluminium chloride modified with (–)-menthol.[5] A glyoxylate compound has been added to N,N-dimethylaniline with a chiral bisoxazoline ligand–copper(II) triflate catalyst system also in a Friedel–Crafts hydroxyalkylation:[6]

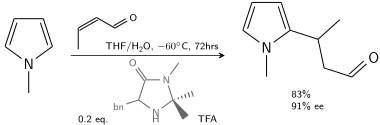

In another alkylation N-methylpyrrole reacts with crotonaldehyde catalyzed by trifluoroacetic acid modified with a chiral imidazolidinone:[7]

Indole reacts with an enamide catalyzed by a chiral BINOL derived phosphoric acid:[8]

In the presence of 10–20 % chiral catalyst, 80–90% ee is achievable.

Other reactions

- Other reactions that follow an electrophilic aromatic substitution pattern are a group of aromatic formylation reactions including the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction, the Gattermann Koch reaction and the Reimer–Tiemann reaction.

- Other electrophiles are aromatic diazonium salts in diazonium couplings, carbon dioxide in the Kolbe–Schmitt reaction and activated carbonyl groups in the Pechmann condensation, hydroxycarbenium ion in the Blanc chloromethylation via an intermediate (hydroxymethyl)arene (benzyl alcohol), chloryl cation (ClO3+) for electrophilic perchlorylation.

- In the multistep Lehmstedt–Tanasescu reaction, one of the electrophiles is a N-nitroso intermediate.

- In the Tscherniac–Einhorn reaction (named after Joseph Tscherniac and Alfred Einhorn) the electrophile is a N-methanol derivative of an amide[9][10]

See also

References

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Vincent A. Welch, Kevin J. Fallon, Heinz-Peter Gelbke "Ethylbenzene" Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_035.pub2

- ^ Gawley, Robert E. (1999-06-04). "A proposal for (slight) modification of the Hughes–Ingold mechanistic descriptors for substitution reactions". Tetrahedron Letters. 40 (23): 4297–4300. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00780-7. ISSN 0040-4039.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "ipso-attack". doi:10.1351/goldbook.I03251

- ^ Asymmetric electrophilic substitution on phenols in a Friedel–Crafts hydroxyalkylation. Enantioselective ortho-hydroxyalkylation mediated by chiral alkoxyaluminum chlorides Franca Bigi, Giovanni Casiraghi, Giuseppe Casnati, Giovanni Sartori, Giovanna Gasparri Fava, and Marisa Ferrari Belicchi J. Org. Chem.; 1985; 50(25) pp 5018–5022; doi:10.1021/jo00225a003

- ^ Catalytic Enantioselective Friedel–Crafts Reactions of Aromatic Compounds with Glyoxylate: A Simple Procedure for the Synthesis of Optically Active Aromatic Mandelic Acid Esters Nicholas Gathergood, Wei Zhuang, and Karl Anker Jrgensen J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2000; 122(50) pp 12517–12522; (Article) doi:10.1021/ja002593j

- ^ New Strategies in Organic Catalysis: The First Enantioselective Organocatalytic Friedel–Crafts Alkylation Nick A. Paras and David W. C. MacMillan J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2001; 123(18) pp. 4370–4371; (Communication) doi:10.1021/ja015717g

- ^ Chiral Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Enantioselective Friedel–Crafts Reaction of Indoles and a-Aryl Enamides: Construction of Quaternary Carbon Atoms Yi-Xia Jia, Jun Zhong, Shou-Fei Zhu, Can-Ming Zhang, and Qi-Lin Zhou Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5565 –5567 doi:10.1002/anie.200701067

- ^ Verfahren zur Darstellung von Benzylphtalimiden Joseph Tscherniac German Patent 1902, DE-134,979

- ^ Ueber die N-Methylolverbindungen der Säureamide [Erste Abhandlung.] Alfred Einhorn, Eduard Bischkopff, Bruno Szelinski, Gustav Schupp, Eduard Spröngerts, Carl Ladisch, and Theodor Mauermayer Liebigs Annalen 1905, 343, pp. 207–305 doi:10.1002/jlac.19053430207